Forget antiwar protests, Woodstock, even long hair. The real legacy of the sixties generation is the computer revolution. We bought enthusiastically into the exotic technologies of the day, such as Fuller's geodesic domes and psychoactive drugs like LSD. We learned from them, but ultimately they turned out to be blind alleys. Most of our generation scorned computers as the embodiment of centralized control. But a tiny contingent…embraced computers and set about transforming them into tools of liberation.

Stewart Brand, We Owe It All To The Hippies, Time Magazine, Volume 145, Number 12 1st of March, 1995

In the opening, frosty weeks of 1966, the author Ken Kesey threw a party at Longshoreman’s Hall in San Francisco. The party was an anarchic gathering of five-thousand babbling freaks in the grip of an acid trip, it alarmed the cops, the city authorities and no doubt the longshoremen themselves. Kesey named it The Trips Festival.

The Trips Festival was the culmination of the Acid Tests, a series of gatherings in and around the Bay Area peninsula, organised by Kesey and his group “The Merry Pranksters”, that had taken place over the preceding couple of years. The Acid Tests were the birthplace of the Hippie movement, and Kesey’s Pranksters were the proto-Hippies. They were people who had experienced something profoundly life-changing in the psychedelic experience, and the Acid Tests were places in which they could commune together, drop acid, and explore the future of humanity.

I wrote extensively about Kesey and the Pranksters in my Lessons from the Counterculture series, particularly in parts 2 and 3: they represented the “religious” side of the ‘60s counterculture, a group that disdained the old, necrotic, repressive systems of power, social conformity and truncated lives of 1950s America and who had opted to drop-out. In contrast to the political side of the counterculture, they saw no future in politics or political action, they saw any engagement with the social system and its institutions as a dead-end; for them, LSD had exploded the fictions of the material world, and human liberation would only be reached through individual transformation, not through collective political action.

Kesey himself interrupted an anti-Vietnam War demonstration at Berkeley University in 1964, pulled out a harmonica, blew a shrill version of Home On The Range to the stunned protesters and shouted at them, “Do you want to know how to stop the war? Just turn your backs on it, fuck it!”, which is a neat summary of the general Hippie approach to politics.

In the minds of Kesey and his Pranksters, man’s highest duty was to himself, and it was only in looking to himself that he would find liberation. Although the Hippies would not necessarily recognise it this way, their philosophy had much in common - accidentally, unconsciously - with some of the theories of the author Ayn Rand, in particular her morality of “rational self-interest”.

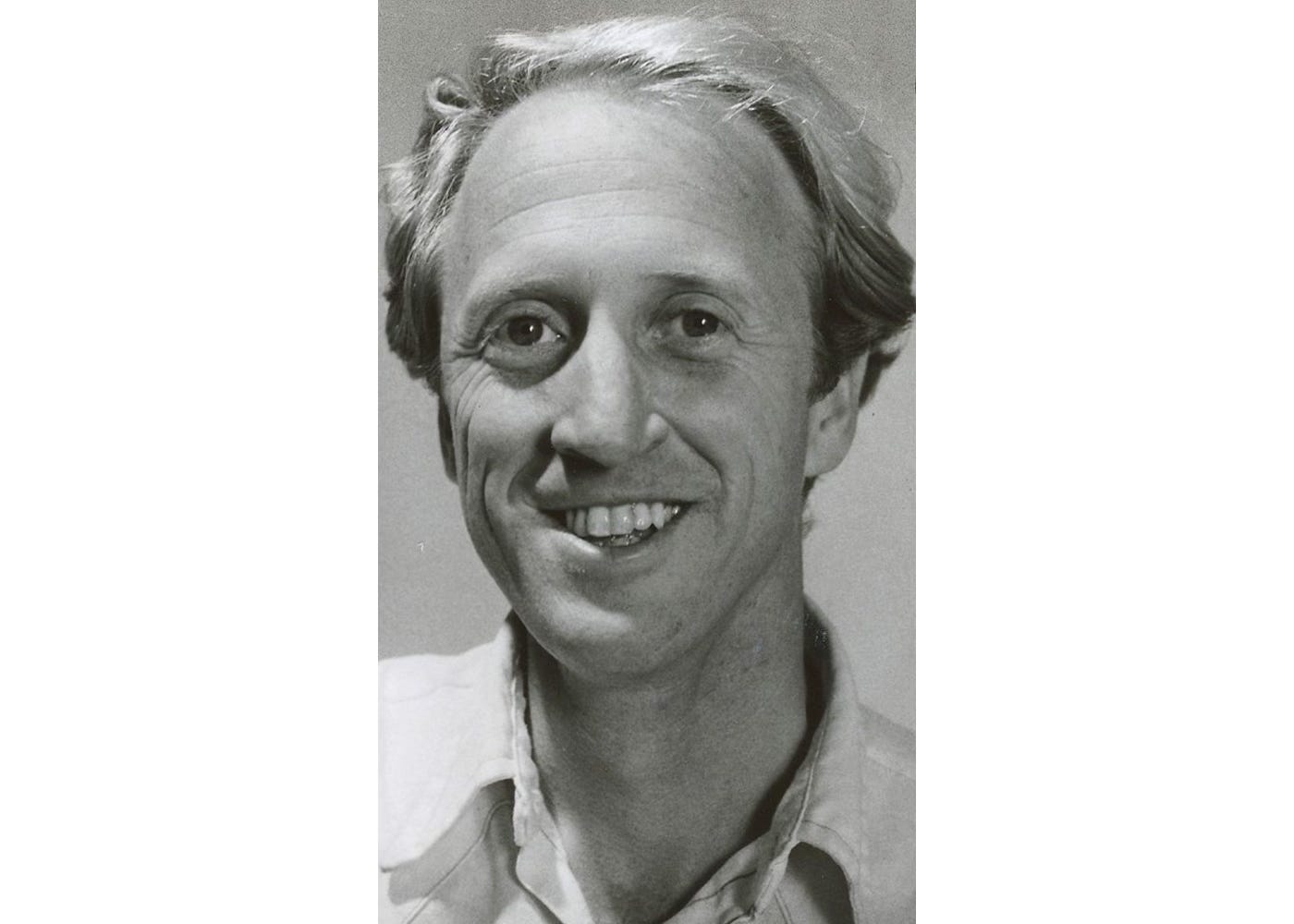

The Trips Festival at Longshoreman’s Hall was the Hippies’ coming-out event, it announced them to world. Although Kesey was its frontman, the charismatic face of the drop-out generation, the celebrity author, he was not the festival’s only organiser: among the three people responsible for putting it together was Stewart Brand, a Prankster associate and counterculture gadfly who appears repeatedly in the histories of the period, including in the opening paragraphs of Tom Wolfe’s famous ‘60s chronicle The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test:

“At the wheel…Stewart Brand, a thin blonde guy with a blazing disc on his forehead too, and a whole necktie made of Indian beads. No shirt, however, just an Indian bead necktie on bare skin and a white butcher’s coat with medals from the king of Sweden on it.”

I contacted Brand some fifteen or so years ago, when I was making a film about the counterculture in San Francisco. We exchanged some emails, he politely declined to participate in the film and I didn’t really push it, back then I had only wanted to speak to him about The Trips Festival, I hadn’t appreciated his wider significance in the story of the counterculture.

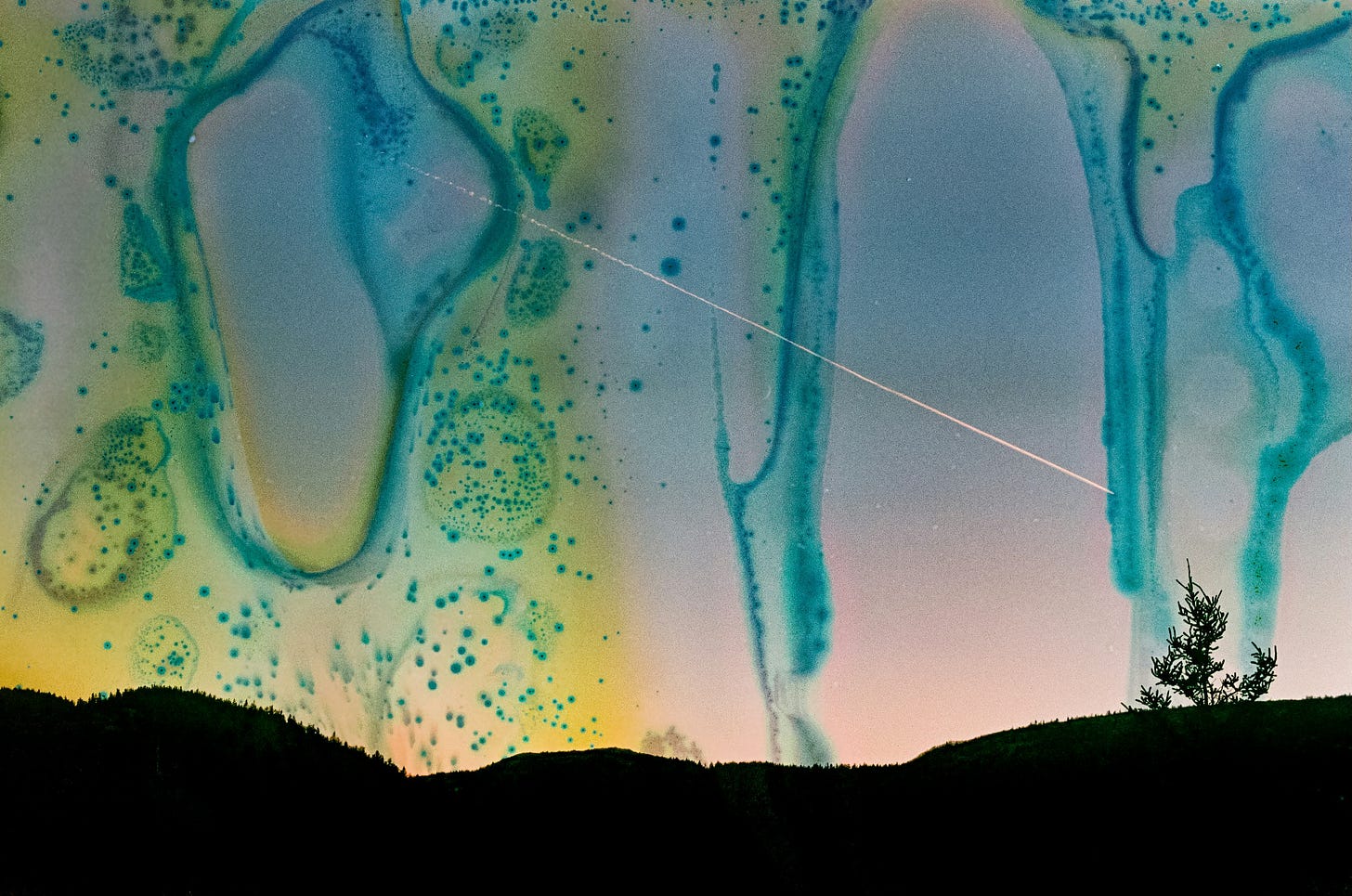

Brand was a leading figure in an obscure sub-tribe within the Hippie movement, which we will call the techno-hippies. While the counterculture is popularly remembered for its explosion of artistic creativity - the alternative literature scene, avant-garde art, the revolution in music and fashion – it also had a lesser-known scientific, technological side. Clustered around the perimeter of the Acid Tests, behind the stage where the Grateful Dead powered through forty-minute guitar odysseys and face-painted, costumed hippies shimmered in projected colourscapes, were small bands of stoned engineers and mathematicians who experimented with speaker stacks and audio technology. Many of these characters, who had names like “Wizard”, ended up working at Lucasfilm, where they pioneered THX sound technologies. And of course LSD itself is a synthetic drug, developed in a laboratory by a Swiss chemist, it is a product of deliberate, scientific technology, rather than a naturally occurring substance handed down by mystics.

The techno-hippies were the counterculture’s left brain. Whereas Ken Kesey and his lieutenant, Kenn Babbs, had been on the creative writing course at Stanford University, Brand had studied biology at Stanford; while Kesey stole a batch of LSD and used it to send bewildered normies off on acid trips, Brand participated in a scientific study of the drug. What the techno-hippies and Kesey’s religious hippies shared, however, was the Libertarian ideology of dropping-out, of political disengagement, of personal freedom.

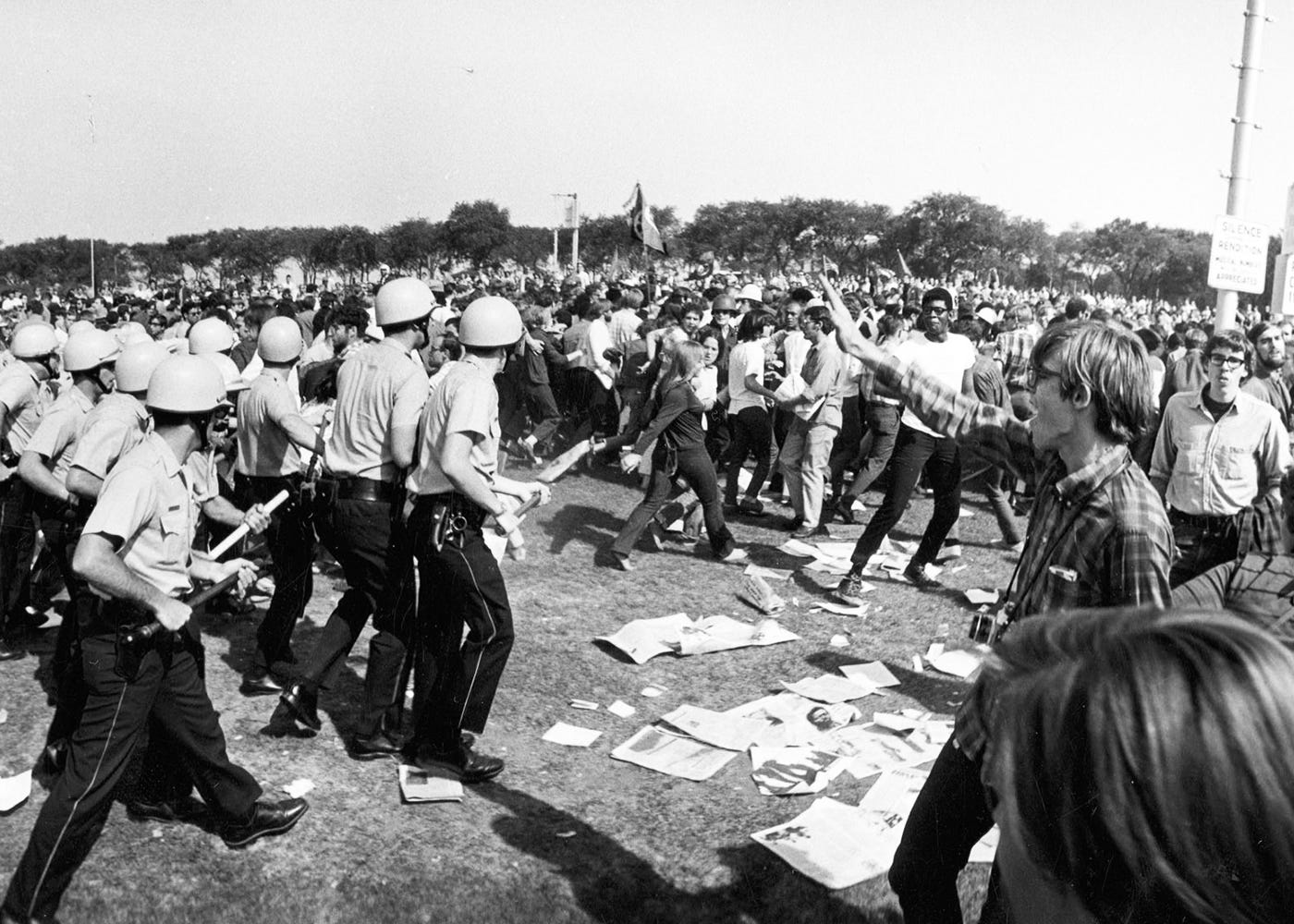

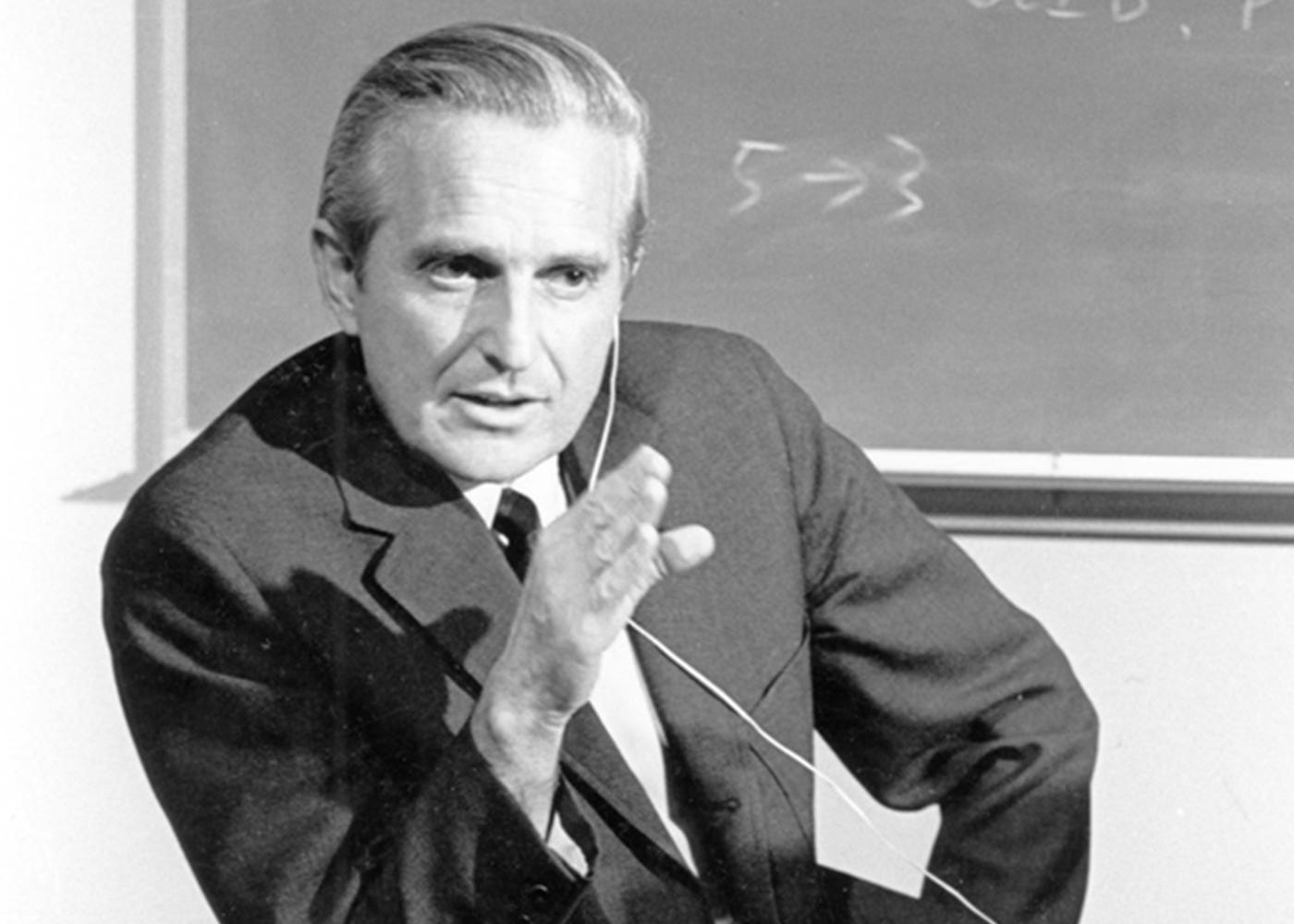

In Lessons from the Counterculture I traced the evolution of the religious and political sides of the counterculture through to the conflagration of 1968, the point of maximum confrontation between the New Left and the forces of reaction. But 1968 was also the key year for the techno-hippies. While American cities burned in the aftermath of the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, while police rioted at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and the anti-war movement turned violent, the techno-hippies prepared to assemble in San Francisco for the Fall Joint Computer Conference, where Stewart Brand and Douglas Engelbart, a forty-three-year-old computer scientist, were scheduled to give a presentation that became known as The Mother of All Demos, it would be the techno-hippies’ revolutionary counterpart to the Acid Tests.

The Mother of All Demos

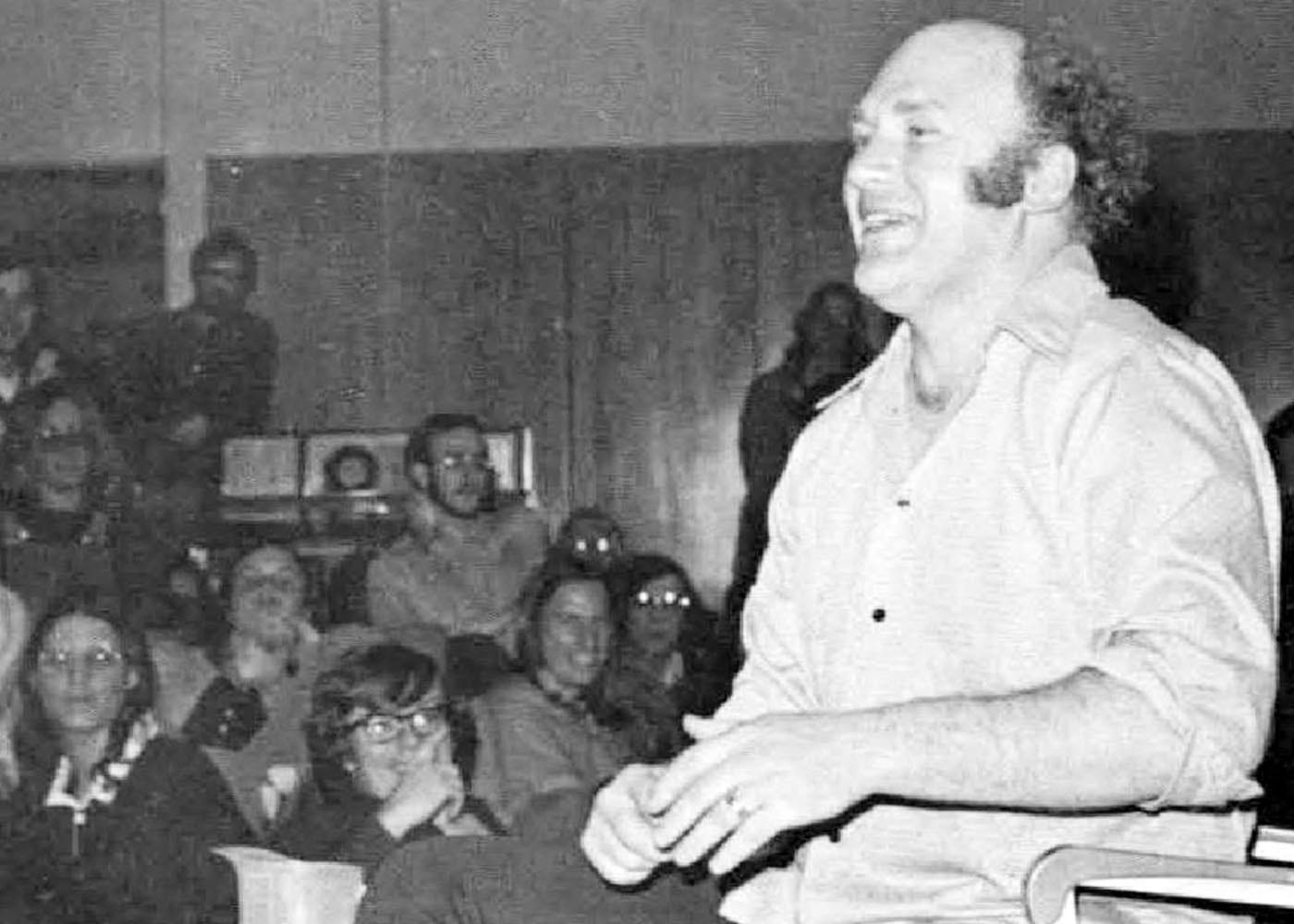

On December the 9th, 1968, a ghostly image of Douglas Engelbart flickered onto a twenty-two-foot high screen above a crowd of nearly three thousand people at the Fall Joint Computer Conference in San Francisco. Engelbart, founder of the Stanford Research Institute's Augmentation Research Center (ARC), announced to the stunned audience that while he was making his presentation, he would be connected to a computer at his lab in Menlo Park, thirty miles away from the conference hall, from where his staff (including Brand) would also participate.

“The research programme that I’m going to describe to you”, opened Engelbart, “is quickly characterisable by saying: if in your office, you as an intellectual worker were supplied with a computer display backed up by a computer that was alive for you all day and was instantly responsive, how much value could you derive from that?"

Engelbart then went on to demonstrate the principal elements of what we would today recognise as a networked, personal computer, a system that he called oNLine: there was a keyboard, mouse, hypertext links, video monitors, screen windowing, word processing programs, and a graphical user interface, all connected by a home-made modem.

Attendees described Engelbart as having “lightening in both hands”, and “it was like Moses opening the Red Sea”.

The oNLine system set the template for the technology that would come to dominate all of our lives, but it didn’t have to be so; computer technology could have evolved differently. Engelbart’s system was a product of his ideology, his vision for what computers could be and how they could change our world, which he described in a 1962 research paper entitled Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework. Computers, Engelbart argued, should be an extension of the human individual.

It was a vision that chimed with the countercultural, Libertarian ideology of Stewart Brand and the young techno-hippies that worked at Engelbart’s research institute, for whom computers were a means of achieving human freedom, liberation from the domination of corporate America and the political establishment, the same vehicle for transcendental self-reinvention that Ken Kesey had found in LSD.

“Our ethic of self-reliance came partly from science fiction”, wrote Brand in We Owe It All To The Hippies, “We all read Robert Heinlein's epic Stranger in a Strange Land as well as his libertarian screed-novel, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. Hippies and nerds alike revelled in Heinlein's contempt for centralized authority. To this day, computer scientists and technicians are almost universally science-fiction fans. And ever since the 1950s…science fiction has been almost universally libertarian in outlook.”

Prior to researching the subject, I had never really considered what computers were for, on a conceptual level. I just experienced computer technology as a useful tool for calculating, writing and playing games, and a crappy tool for painting. As the technology and its capabilities expanded, I uncritically adapted these capabilities into my life without thinking that deeply about where they had come from, or the motivations behind their development.

But in asking the question what are computers for? and studying some of the answers provided by computer pioneers like Douglas Engelbart and the techno-hippies, we are better able to understand the ideologies that glow behind our screens, and what that has meant for modern life.

In the next part we will look at those ideologies and concepts: where computers came from, Engelbart’s Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework, and where the libertarian techno-hippies, in particular Stewart Brand, took his vision.