Lessons From The Counterculture Part 3/9: Hippies & Angels

The strange alliance between outlaw bikers and the love generation

Note: this series is intended to be read in sequence, and this part makes references to personalties and concepts developed in the preceding parts.

“Despite the machines they ride and worship, they insist that their main concern in life is ‘to be a righteous Angel’, which requires a loud obedience to the party line. They are intensely aware of belonging, of being able to depend on each other.

This desperate sense of unity is crucial to the outlaw mystique. If the Hell’s Angels are outcasts from society, as they freely admit, then it is all the more necessary that they defend themselves from attack by ‘the others’ – mean squares, enemy gangs, or armed agents of the main cop. When somebody punches a lone Angel every one of them feels threatened. They are so wrapped up in their own image that they can’t conceive of anybody challenging the colours without being fully prepared to take on the whole army.”

--Hunter S. Thompson, Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs

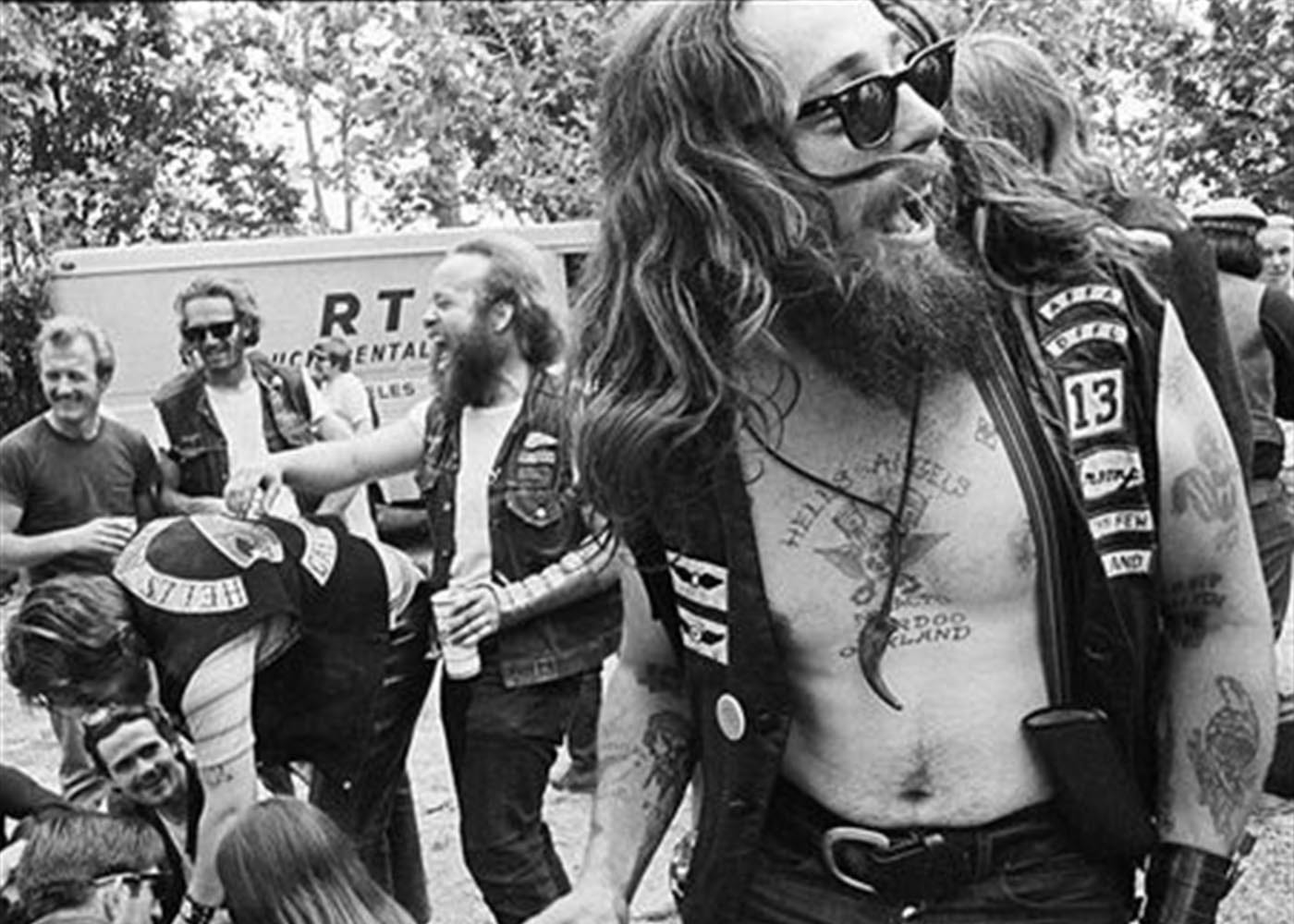

The Hells Angels are omnipresent in the footage of the Acid Tests. Lank, greasy hair, patchy beards and filthy leathers, dancing awkwardly opposite blissed-out teenage girls. There’s one! stumbling precariously across the room, seized by whatever terrible hallucinations are escaping from his damaged psyche. He lifts his hand up in front of his eyes, splaying the fingers and turning it rapidly between the palm and back, mouth agape, before fighting on through on the strobing colours and twisting bodies. They’re everywhere, everywhere, a weird, primal energy squatting amongst the bright, ecstatic youth.

The Angels had quickly become an intimate part of the early Hippie scene. It was a discrete nod from Angels in the Longshoreman's Union that clinched the Union Hall for the Trips Festival, hippies stranded by the roadside next to a steaming love bus might be lent a spanner and a jump start by a passing Angel, they were silent, willing drug couriers and useful roadies, a brute race of Morlocks that accompanied the hippie Eloi on their journey to the future. But when I raise the matter of the Hell’s Angles with the Grateful Dead’s laughing manager, Rock Scully, his smile plummets and his eyes expand: “these guys are Vietnam veterans and Korean War veterans” he says with urgent fear, as if I’m about to invite the local Angels chapter to join us in his living room, “you don’t mess with them and you don’t ask them for anything, ever. Other than to be peaceful”.

The Angels roared into Ken Kesey’s life in late ’65, while he was out drinking with the infamous progenitor of “Gonzo Journalism” Hunter S. Thompson. Thompson had spent a delirious year embedded with the Hell’s Angels and he had a couple of bikers in tow when he first met Kesey. The whole band hit it off famously, united by a shared enthusiasm for drink, drugs and disobedience.

“Kesey invited the Frisco chapter down to La Honda for a party”, Thompson records in Hell’s Angels, a memoir of his time with the gang. “[He had] a sign on his gate saying ‘The Merry Pranksters Welcome The Hell’s Angels’. The sign, in red, white, and blue, was fifteen feet long and three feet high. It had a bad effect on the neighbours…five San Mateo County sheriffs’ cars were parked on the highway in front of Kesey’s property. About ten Angels had already arrived and were safely inside the gate; twenty others were said to be en route”.

In Thompson’s account, the life of an Angel is an aimless procession of violence and hedonism. And rape. A disquisition on rape runs throughout Hell’s Angels, including an especially repugnant episode in which a fourteen and a fifteen-year-old girl (one of them pregnant) are gang raped by a baying phalanx of drunk bikers. It is accompanied by a disgusting disputation on the part of the Angels about whether the girls were really “asking for it”.

These were the specimens that Kesey and the hippies chose to identify as, and here I deliberately use a term popular in our current culture wars, “allies”. In this gang of primal, libidinous thugs, a motorised Mongol horde, the hippies saw noble anti-establishment free spirits and iconoclasts, the shock troops of the coming consciousness. This was a slow-minded and dangerous confusion between transgression and progression, a mistake repeatedly made by “progressives”, even now.

In the postscript to Hell’s Angels, Thompson describes the moment when the Angels turned on him, beating him into the hospital, ribs snapped and spitting blood. The book makes no mention of the reasons behind the attack, but a year later Thompson is being interviewed on television in front of a live studio audience, where he is confronted by an offended Hell’s Angel named Cliff and the beating is brought up. The reaction of the audience is particularly instructive.

Cliff rides his Harley into the centre of the studio, where Thompson and the interviewer are seated, and begins circling them as the audience whoops and claps. His entry is received in the dominant postmodern mode: irony. The audience laugh along in admiration at Cliff growling around the neatly arranged studio in his leathers, intimidating the squares, refusing to acquiesce to the demands of polite society and its conformist media (notwithstanding that this is all, of course, choreographed by polite society and its conformist media). The only person in the studio who seems to take this deadly seriously, who shifts in discomfort, pulls on a cigarette, is Thompson himself.

The discussion arrives at the difficult subject of Thompson’s violent break with the Angels and Cliff outlines the justification: “Junkie George is beating his old lady”, the audience explodes in laughter, “Junkie George’s dog bit him”, the laughter intensifies, Cliff starts grinning, obviously enjoying his moment, “to me this is a personal feud, if a guy wants to beat his wife and his dog bites him, that’s between the three of them”. The audience collapses in hilarity, applause breaks out, whistles of approval. Cliff gestures contemptuously towards Thompson: “here comes this peacemaker, he doesn’t have a patch on, he isn’t in the club. Junkie George is stiff and you walk right up to him and you say ‘only a punk beats his wife and dog’. These were your words…and he said ‘Hunter, you want some of this?’ and you said ‘no’, but you got it anyway.”

Cliff strikes me as someone who is fully self-aware; he is clear on who the Hell’s Angels are and he has no compunction about saying it. They are creatures of pure inclination, Libertarianism in its most extreme form, where each individual acts according to his immediate, temporary desires and moral schemes are either relative or subordinate to the principle of “being true to oneself”, however ugly that may be.

Hunter Thompson’s intervention, on the other hand, was born of obedience to absolute moral injunctions: “only a punk beats his wife and dog”. For the Angels, violence inflicted on others is just a “personal feud”, a privatised matter of individual conscience and consequence. For the Angels it is Thompson who is the transgressor, his attempt to constrain Junkie George a greater crime than the violent beating George is visiting on his wife. The fists and boots that rain down on Thompson, the mask of blood, the smashed rib cage, as the Angels see it this is all proper justice and retribution.

In Cliff’s court, the aggravating factors are also revealing: “here comes this peacemaker, he doesn’t have a patch on, he isn’t in the club”. This is where the politics of identity make their entry, and the notion that the value of any proposition or objection depends on who’s making it. In this instance, that Hunter Thompson doesn’t “identify” as a wife-beating Hell’s Angel precludes him, in the mind of the group, from coming to the defence of a woman being subjected to explosive, brutal male violence (our contemporary culture war is riven with this poisonous anti-thought, it abounds in concepts like ‘positionality’ and remarks prefaced with the phrase “speaking as a…”).

Both Hippies and the Angels came to exhibit a type of Communal Individualism, groups and collectives that form around protecting and asserting various forms of individualism, protecting the primacy of individual desire and struggling against its perceived enemies.

This is completely different from the collectivism of the traditional Left, which seeks to find and assert the universal, rather than the specific, and that old Left concept of Solidarity is very different from the nebulous, modern concept of Allyship, which appears to be little more than uncritical chauvinism or, like almost everything in the Instagram era, a hollow aesthetic position.

These are the politics of feeling, of emotion and sensation, rather than reason, a perfect engine for conflict, as desires, wants, demands, as narcissistic identities abrade one another - as Thompson said of the Angels, “they are so wrapped up in their own image that they can’t conceive of anybody challenging the colours without being fully prepared to take on the whole army”. This was the mistake that Thompson made, he broke through the solipsism, he appealed to the universal, “only a punk beats his wife and dog”, and he was punished for it.

It’s interesting, watching the TV debate between Cliff and Thompson, how much the audience laughs and applauds at Cliff’s disgraceful remarks and how genuinely disgusted, and alone, Thompson is. The warm fascination with outlaw bikers on the part of bohemians and liberals was a phenomenon that he touched on in Hell’s Angels: “The Angels had become a factor to be reckoned with in the social, intellectual and political life of northern California…no half-bohemian party made the grade unless there were strong rumours that the Hell’s Angels would also attend [and where the guests] wanted to talk about ‘alienation’ and ‘a generation in revolt’…the only real problem with the Angels new image was that the outlaws themselves didn’t understand it. It puzzled them to be treated as symbolic heroes by people with whom they had almost nothing in common”.

I remember once talking to Pamela Des Barres, the original groupie, priestess of L.A.’s bohemian “Freak Scene” (the local, hippie-esque counterculture, in which the musician Frank Zappa was the key figure) and muse/concubine to rock stars from Jim Morrison to Jimmy Page. She raised her arms while she spoke, pushing out her elbows and grimacing: “we were trying to break out of the old, ‘50s straitjacket”. This hints at the attraction of the Angels for the progressives of California in the ‘60s – they were radicals, free spirits who had snapped the bonds of the ‘50s straitjacket.

Publicly transgressing the social and moral codes of the 1950s is what wins Cliff the approval of the studio audience, who are happy to applaud snappy aphorisms like “to keep a woman in line, you got to beat ‘em like a rug once and a while”. It’s a funny thing, approving of this; apart from being morally repellent, Cliff’s remarks are, in their general affirmation of patriarchal violence within the context of traditional domesticity, a pretty strong endorsement of the conservative, reactionary politics of the 1950s. Of course, the whole performance is cloaked in irony, hence all the laughter from the bleachers, it’s only Thompson who refuses to legitimise the irony, and instead insists on taking it deadly seriously, and at face value. The audience want their radical and a radical Cliff may be, but not in the sense they think. Sometimes it’s important to call a spade a spade and Hunter Thompson understood this, the studio audience, and the hippies, did not.

The Counterculture sprung from hopeful rebellion. Rebellion against the establishment of the 1950s and its conservatism, racism, social hierarchies, demands and prohibitions. Beats, bohemians, progressives and Angels were all joined in a communal struggle for individual liberty in a new American future. That is why a liberal TV audience applauded Cliff, or what Kerouac meant when he described the proto-hippie Neal Cassady as “a new kind of American saint”. You might think that a new progressivism built on pacifism, equality, civil rights, liberty and anti-discrimination would explicitly oppose the attitudes of a violent, misogynistic biker gang, until, that is, you contemplate the ideological centre of this nascent Counterculture: “the patients will be free”. The Angels had broken out of the Institution, and they were ‘being true to themselves’, just as much as the hippies.

“It was about an American tradition, which is a notion of freedom that fails to carry with it the measure of social responsibility that I think ideally goes with freedom. Hippies were like that, the Angels were like that”, Robert Christgau tells me. “The Angels were more violent, supposedly, a little worse to women….hippies were not so great either. Yes, they were different and I prefer the hippies, sure. But I don’t think that they were diametrically opposed”.

This is the lesson that I took from the story of the Hippies and the Angels, that aimless notions of freedom and rebellion are dangerous ends, that it is incredibly easy to mislocate ideology, and that freedom in which responsibility towards others is less important than the satisfaction of one’s own individual desires is the ideology of the Right. That, in blindly and superficially casting all rebels as allies and all critics as allies of one another, the Counterculture made both friends and enemies injudiciously, without due regard for the character of either, the same misplaced sense of belonging and obedience that motivated the Angels.

The danger in constructing a two-sided culture war is that it can’t be won, it devours itself through the same logic of narcissism and solipsism that infects the identity politics that drive it. In order to be an in-group, there must be an out-group, to be a Hell’s Angel was to be an outcast from 1950s square society, to menace it by roaring along the perimeter in oily denims and a Death’s Head patch, middle finger raised; to choke it with black smoke and fumes, to beat its men and rape its women. This was the Hell’s Angels identity, so powerfully felt, but it required 1950s square society in order to exist at all, without that, with real, meaningful, permanent social change that took the whole of society into account, the Angels would represent nothing more than people who liked to ride motorbikes together. They would have no symbolic value to the Counterculture, or to the liberal TV audience that applauds Cliff’s violence.

Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters undoubtedly had an important subversive purpose, but their role in achieving serious, radical social change could only ever be a limited one. Ultimately, the philosophies of tripping court jesters stuffed into a shambling rainbow bus are not the best basis on which to construct a new society. The real question is once the patients have been freed, what will they do with their freedom? Well, as LuAnne Cassady said, “Neal will leave you in the cold anytime it's in his interest”. That was the warning for the Counterculture, the apple in the garden.

Leaning back in his wrinkled leather armchair, Christgau is wrapping up his answer: “Yes, they were different and I prefer the hippies, sure. But I don’t think that they were diametrically opposed. Who is diametrically opposed? My side of the Counterculture, the political people. We understand that the Angels are no good, I don’t think that the religious side [the hippies] understands it that well because they’re….too stoned”.

For Christgau, the Pranksters’ individualistic, personal revolution, in which consciousness will change America, is not the whole story of the Counterculture: “the so-called Counterculture of the 60s was divided into two parts. It had its religious part and its political part. The religious part was much bigger than the political part, say two to one, three to one. Hippies were the religious part. The so-called “Movement”, the Left, was the political part”.

I’m unconvinced that the distinction was as clear as Christgau would have it, but that there was a political “Movement” is indisputable, and by the mid-60s it was gathering momentum.

Next — Lessons From The Counterculture Part 4: The New Progressivism

Reading:

Hunter S. Thompson - Hell’s Angels

Martin A. Lee & Bruce Shlain - Acid Dreams

Tom Wolfe - The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test