Lessons From The Counterculture Part 2/9: The Psychedelic Wave

How drugs created a new American freedom

Note: this series is intended to be read in sequence, and this part makes references to personalties and concepts developed in the preceding part.

“Have nothing to do with identity politics. I remember very well the first time I heard the saying ‘The Personal Is Political’. It began as a sort of reaction to the defeats and downturns that followed 1968: a consolation prize, as you might say, for people who had missed that year. I knew in my bones that a truly Bad Idea had entered the discourse. Nor was I wrong. People began to stand up at meetings and orate about how they 'felt', not about what or how they thought, and about who they were rather than what (if anything) they had done or stood for. It became the replication in even less interesting form of the narcissism of the small difference, because each identity group begat its sub-groups and "specificities." This tendency has often been satirised—the overweight caucus of the Cherokee transgender disabled lesbian faction demands a hearing on its needs—but never satirised enough. You have to have seen it really happen. From a way of being radical it very swiftly became a way of being reactionary; the Clarence Thomas hearings demonstrated this to all but the most dense and boring and selfish, but then, it was the dense and boring and selfish who had always seen identity politics as their big chance”.

-Christopher Hitchens, Letters To A Young Contrarian

1968

The youth are running, in New York, San Francisco, London, Paris, Prague and Berlin thousands of pairs of legs strobe past. Glass bottles break against the shimmering barricades, sending sheets of flame towards the cops. Gas contrails arc across the sky, long hair and dirty Levis duck for cover, wet red bandanas pressed against mouths as bullets, flares, cannisters, shells, shot, cannons crack and echo off the blocks.

The Youth are here. The babies born in the shocked aftermath of World War 2 are of age and have some demands: an end to the frozen trauma, no more silence, no more business as usual, no more repressive, sclerotic old men and their wars, racism and violence, or silence and complicity. No more shame, no more staying in your lane, no more women in their place, no more money race, no more that’s enough and no more - be grateful. No more Christian guilt. It’s been coming. During the love-ins, the acid trips and marijuana haze, the flowers, poetry readings and protest songs it was approaching, and now it's here, the future, time to fight for it.

In January the North Vietnamese swarm from the jungles in a massive offensive, overwhelming the US Army and putting the lie to Lyndon Johnson’s claim that America is winning the war. Student protests and demos erupt across the country, demanding an end to the war and the removal of Johnson from office, the protests are replicated in cities across Europe.

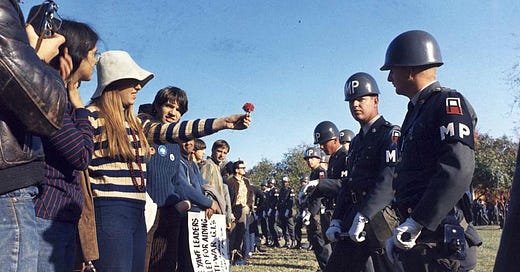

The Civil Rights Movement continues to march, expanding its original mission of racial justice to demand economic and social rights for the poor and dispossessed throughout America, but as its purposes intensifies so does the violence. Terrified racists crowd columns of black pacifists with rows of armoured cars and rifle-carrying guardsmen, dogs are loosed, snarling and barking while fat sheriffs grab and club helpless demonstrators and summary executions pile up bodies in the south. Hours after Martin Luther King describes his vision of the Promised Land to the hopeful faces of striking workers in Memphis, he is shot to death on a dreary motel balcony.

Spring comes to Europe and the old order starts to burn away in the heat of the sun. The cold Soviet grip on the East strains under the weight of democratic uprisings in Prague and Belgrade. Students in Paris rise up against capitalism and its imperialist wars. Running battles in the streets between the state and the future, the revolution is here, 11 million workers rebel in sympathy, thousands of pairs of legs strobe past. President de Gaulle takes flight in fear of the guillotine, a midnight escape to seek the protection of his old enemies in Berlin.

British youth storm the US embassy in London, a wave of police horses breaks over the hedge rows that ring the building and rushes up towards the crowd, cracking skulls and shoulders with oak truncheons. Protests and sit-ins roll across the schools and colleges: end the war, solidarity with Vietnam.

Robert Kennedy promises the future to the youth and calls for racial unity in honour of Dr. King, “We have to convince the Negroes and poor whites that they have common interests. If we can reconcile those two hostile groups, and then add the kids, you can really turn this country around”. By August he is lying in a pool of blood on the floor of a hotel kitchen, his head cradled by an 18-year-old bus boy, he will not be the future.

More protests, sit-ins, riots, confrontations, police violence, the future’s coming. Who will run for President in Kennedy’s stead? A nominee is to be selected at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, 10,000 protestors descend, Yippies, Black Panthers, women’s groups, Students for Democracy, Committee to End the War, the youth are running, thousands of pairs of legs strobe past. 23,000 cops ready for war, blood streaming down the split faces of American children, batons and rifle butts raining down on terrified students prone on the ground, palms held out in surrender, screaming rebels hoisted aloft, their arms twisted backward in cuffs. Gas contrails arc across the sky, long hair and jeans duck for cover, thousands of pairs of uniformed legs strobe past, chasing out the future.

In the autumn, on a quiet, cold morning in Washington, President-Elect Richard Nixon pulls up his chair and begins work. In Prague, frost crawls along the surface of silent Soviet tanks in cowed, deserted streets. In Paris, the half-remembered chants of “Adieu, de Gaulle!" no longer disturb the President’s sleep, and the promises of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy lie entombed with their corpses, six feet beneath the earth. The defeats, the downturns.

The climatic violence of ’68 was the apex of the Counterculture, the point of maximum pressure on the established order, the moment of confrontation. The youth of the post-war baby-boom came of age in the 1960s and when President John F. Kennedy, their President, was assassinated in ’63 and the Civil Rights Movement marched across the southern states, they rebelled against the political-economic establishment. It was an inter-generational struggle that spread to most democratic societies: “don’t trust anyone over 30” was their maxim.

The Counterculture was a revolutionary cultural movement that sought to break the established systems of authority, struggle for economic and racial justice, end white supremacy, embrace varied concepts of sexuality and gender and promote women’s rights. In short, the main themes of our contemporary culture wars and political conflicts. In ’68 it came for political power, hurling itself against the The Man’s grey granite cliff face, but the rock held and a few too many bones were broken in the effort. A few years later and the movement had more or less petered out, a decade on and the world’s most dynamic revolutionary force emerged on the Right, unlike the Counterculture it was united, ruthless and successful. Regan took the White House, Thatcher, Downing Street. Monetarism and the Neoliberal dark age began which, of course, remains with us.

Christopher Hitchens perceived the entry of identity politics to be a consequence of the Left’s reverses in 1968 and the political defeat of the Counterculture, but identity politics (or, at least, the philosophical seed of identity politics) was always encoded in the Counterculture, in the 1970s it simply became dominant. To an extent the failure of the Counterculture was inevitable, prophesised by its own contradictions. The politics of identity are a virus that originates on the Right but, at times, has found a willing host on the Left, Hitchens saw it for what it was.

There are lessons back there in the Counterculture, lessons worth revisiting, lessons that, if learned, might help prevent new defeats, new downturns. The blood remains on those old battlefields, soaked into the earth, and in the rush to claim the future the modern Left risks sinking in it. It has already made its first serious mistake, that is to adopt identity politics of the type described by Hitchens; its second mistake would be to misunderstand, as the ‘60s Counterculture did, what it is to be an outlaw motorcyclist.

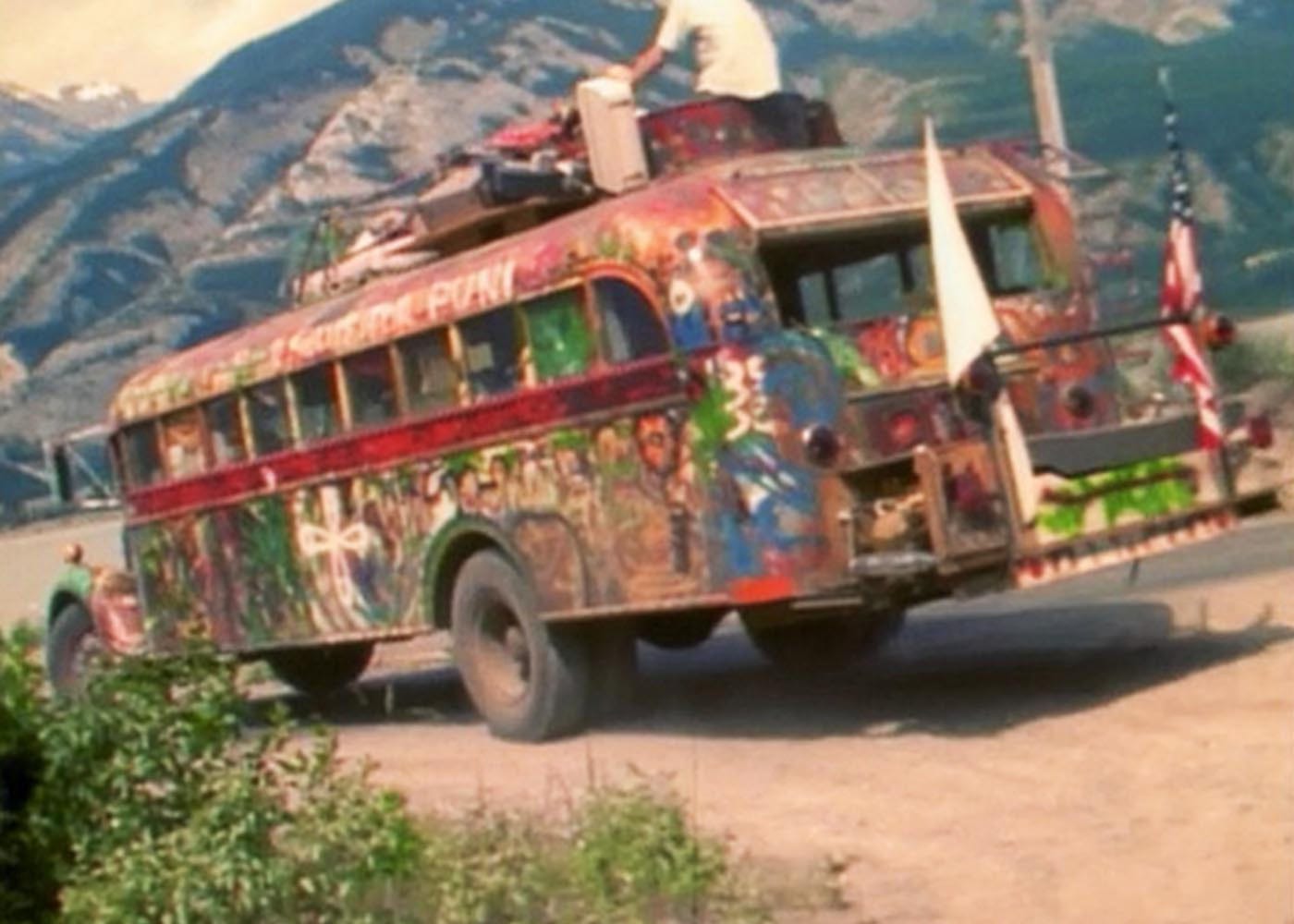

Robert Christgau is looking up to the heavens, his mouth open, swinging gently on its hinges, his head nodding and lilting, brow furrowed, as if he’s experiencing a particularly tiresome epiphany. This is what Christgau, an irascible New Yorker sometimes called “The Dean of American Music Critics”, does when he either finds your question interesting and is searching for an answer or finds your question idiotic and is searching for an insult; impossible to know which until it comes.

It is a decade or so ago, when social media was in its shit, vomit and howling days and we were yet to see the psychopath that it would grow up to be. I am sitting opposite Christgau in his hunched Greenwich Village apartment, tumbling walls constructed from books and cds, relentless noise invading from New York’s war of horns and drills.

Christgau is one of the first ever professional music writers, a tribe that emerged from the youth movements of the 1960s, when the electric energy of Rock and Roll powered the social revolution. Music critics of this era were more than just commentators on some band or album; they were diarists, ethnographers, rainmakers, they interpreted the chaotic promise of the time for those who were too drunk, or stoned or young to understand it. They wrote about the future. I am here because I’m making a film about the Counterculture in 1960s San Francisco, and I have some questions about the past.

Christgau’s face exhausts its struggle, serenity arrives. He looks directly at me: “The hippies could get along with the Hells Angels because their minds were sufficiently open that if they laid down their brains would fall out”. His final expression is one of contempt, it silently calcifies.

It’s easy to become dazzled by the Counterculture in San Francisco, people’s eyes dilate when confronted by the acid and nudity, much of the writing on the subject devolves into a kind of weightless pean to Jerry Garcia’s guitar work and guiltless fucking. But push through the kaleidoscopic parties in Golden Gate Park, the flowers and face paints, naked drum circles, speaker stacks on flatbed trucks, draft cards burning, Grace Slick, communes, clenched fists, impassioned anti-Vietnam speeches screamed through loud hailers and impassive ranks of National Guard touching their triggers and you might notice, as I did, a persistent, disturbing anomaly: the ubiquitous presence of Hells Angels.

Looking through the film archives, I found Angels everywhere: among the crowd at the Be-In; climbing off a Harley on Haight Street; sitting on top of a speaker, swinging a leg and necking a beer at a Grateful Dead gig. There was always an Angel, black leather twisting discretely through the bright primary colours like an ink blot, as if placed there at some later time by an avant-garde video artist interested in subverting classical notions of mise-en-scéne.

I found it to be a mysterious and disconcerting phenomenon – what were these gentle hippies, “the love generation”, harbingers of the coming consciousness, doing in confederacy with a band of ultraviolent, reactionary stormtroopers? I relegated all my other enquiries about the Counterculture to an order of importance below this one.

Stay with me, the history is important. It begins with…

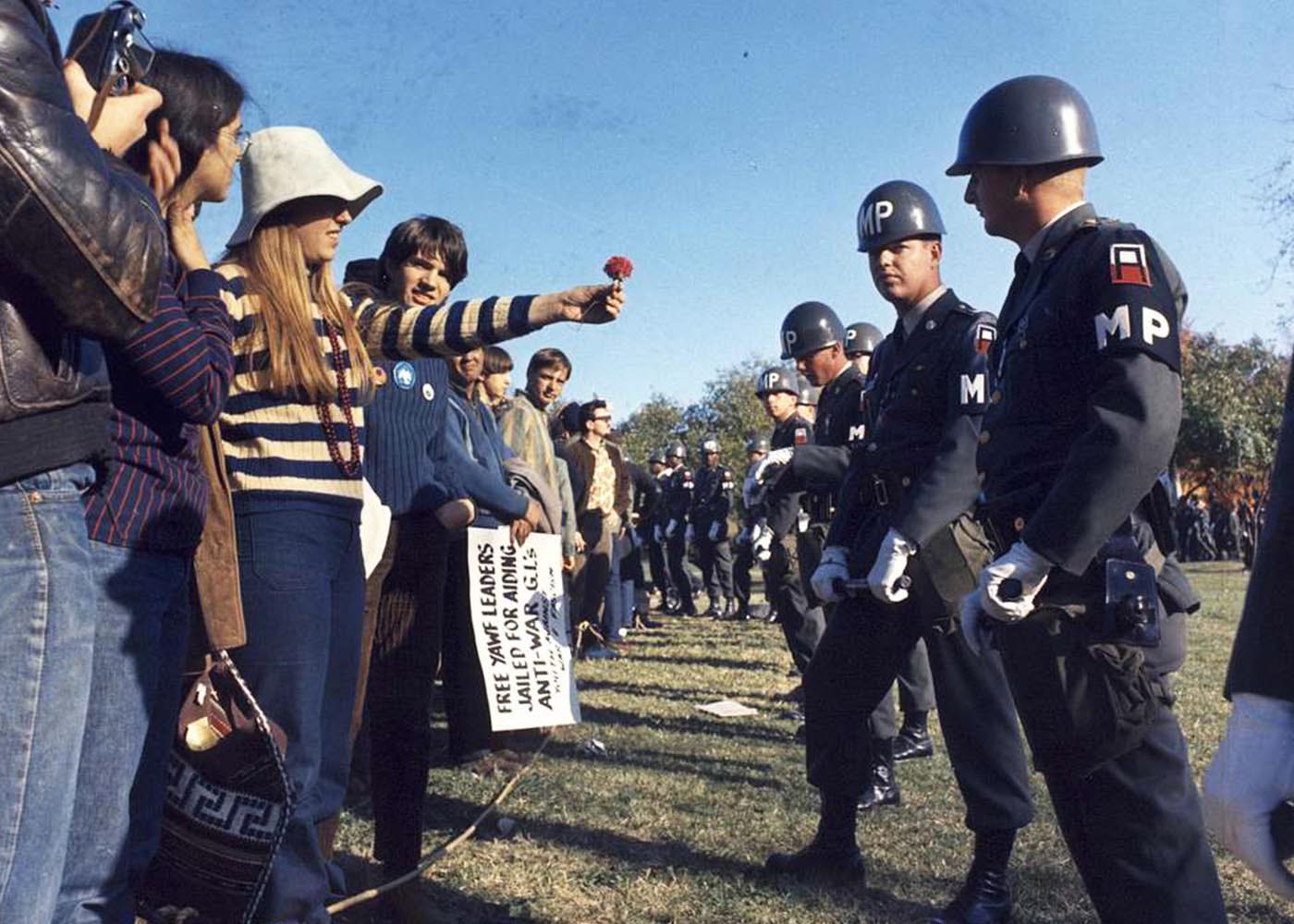

The Magic Bus

I’m in rural Oregon, where a limitless blue wall descends to meet a narrow, shimmering gold strip on the horizon and dust devils spiral upwards like spirits escaping the dead. All is silence and heat. I’m at Ken Kesey’s ranch, leaning on the bonnet of ‘Furthur’, an old, 1930s yellow school bus painted all over with intricate, psychedelic murals. Kesey, most famous as the author of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, died some years ago, but the ranch remains in the family and I’m here in the company of Ken Babbs, his long-time lieutenant.

Babbs, a tall, clean-cut man in his mid-seventies is dressed formally in pressed trousers and a starched white shirt, although a lurid, day-glo yellow, blue and green long-sleeve t-shirt creeps from beneath his cuffs. He is rolling a joint, I’m smoking a cigarette, it’s uncomfortable. I always hated smoking in hot weather, the hot breath, hot smoke, hot lungs, hot, clammy fingers stained dark from the nicotine pressed from the dank, sweaty cigarette butts. I peel off to go and look for water, Babbs whistles and motions me back, he hands me a small box stuffed to overflowing with drugs of various type, “that’s for your trip”, Babbs chuckles, and his mouth expands into a thick, toothy grin. I’ll eventually have to toss the box at Portland International, having managed just one furtive, midnight joint outside the airport motel, panicking every time my hidden corner is strafed by the glare of incoming aircraft, while in the distance my cameraman rages at Albanian roadtrippers and their euro-techno rave-up on the motel balcony.

The shirt, drugs and half-witted grinning are all part of Babbs’s performance, I detect that the real Babbs is sharp and sceptical, but he does a good job of hiding it, pitching instead for Village Idiot; it’s an act that reflects his seniority in the “Merry Pranksters”.

A roving band of “psychedelic cosmonauts” that orbited Ken Kesey in the early ‘60s, the Merry Pranksters traversed America on Furthur, stopping randomly in the towns dotted along the conservative belt strapped around the nation’s midsection, and dispensing acid to bewildered locals. This was the beginning of the Hippie era, the pre-history. I ask Ken about it. Ken waves a finger in the air, his voice soars in proclamation: “It is I, the intrepid traveller, come to lead his Merry Band of Pranksters across the country and back, in the opposite direction of the settlers, and our avowed mission – the institution will be institutionalised and the patients will be free!”.

After recomposing himself Ken offers a more cogent summary: “it would be this bus going across country and stopping, and everywhere we stopped something would happen. We always took a little bit of the LSD that we kept in an orange juice jar, so it would not only be the bus, the drama, the local people, us interacting with them, and us high – see? So this is a stew that had never been cooked up before”.

The Pranksters had started life after Ken Babbs and Ken Kesey met on the creative writing programme at Stanford University in the late 1950s, both supported their studies through means which would bring them into contact with what modern conspiracy theorists would call the “deep state” and, as a consequence, both became convinced that America was in need of radical change.

Babbs’s education had been financed by the Naval Officers Reserve Training Corps, and when the course wrapped up the US Marines called in the debt. Babbs was dispatched to Vietnam, where the looming war was in its covert phase, disguised from the American people. For two years he flew his helicopter over the serene jungle carpet that the US army would eventually obliterate, the reaching, ancient palms collapsing in rows like grass under the blades of a lawnmower, columns of flame surging up into the skies, staining the heavens black and orange while below floating corpses leaked blood into the rivers and the roads were strewn with the remains of incinerated children. He returned to the US a changed man.

Back home in California, meanwhile, the umbra of secretive government agencies had also fallen on Kesey. In the 1950s the CIA initiated Project MK-Ultra, a sort of deranged tribute to the obscene human experiments conducted by Nazi sadists a decade earlier. While the GIs that first entered Hitler’s camps regarded the starved, shrunken bodies and extirpated minds that limped amongst the corpses with a mixture of suspended horror and incontinent rage, their superiors in the intelligence services perceived an impressive exhibition of scientific research, with sensational prospects for the future torture and subjugation of America’s enemies. Celebrity Nazis were invited to Fort Detrick, Maryland, where they lectured eager CIA suits on the use of Mescaline at Dachau and Sarin gas at Auschwitz.

MK-Ultra aimed to rationalise these primitive Nazi enquiries into psychoactive substances and the extremes of human experience. The purpose of the project was to learn how to manipulate the human mind, manoeuvring it between the poles, between madness and sanity, between reality and delusion: means of enhancing or reducing the effects of alcohol, methods to improve perception or cognition, or to erase the memory, to produce confusion on command, to disorientate over extended periods of time, to induce hypnotic states, to destroy ambition and derange the senses. It was a metaphysical assault on the individual, torture elevated beyond the application of bodily suffering, directed to distort or delete the subject’s sense of self and concept of being. It was also illegal, the experiments having been conducted on American citizens without their informed consent, a collection of citizen guinea pigs that included Ken Kesey.

Kesey was working as an aide in the psychiatric wing of Menlo Park Veteran's Hospital, in the part of the Bay Area that would later become known as “Silicon Valley”, when he volunteered to become a test subject in an MK-Ultra study; the role of the CIA and, naturally, the existence of MK-Ultra, remained concealed from the volunteers.

The study battered its subjects’ consciousness with a succession of powerful hallucinogens: Mescaline, Psilocybin, DMT and LSD. For Kesey, this “psychedelic experience” was profound, life-changing. In later interviews he said “there’s something about seeing reality with a new light shined on it that goes right from your eyes to your fingertips…it’s a shortcut to enlightenment for those of us who would like to go on to better realities. I believe that with the advent of acid we discovered a new way to think”.

The substance of Kesey’s epiphany is encoded in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, his Book of Revelation. The novel concerns events in a psychiatric hospital, of the type in which Kesey worked. Patients are committed as “insane” because they refuse to conform to society’s demands and expectations, the institution deploys various techniques to discipline and coerce inmates, techniques that deceive the inmates into colluding in their own subjugation. Ultimately, Kesey suggests, it is the institution that is insane, not its patients.

The novel functions as an allegory for American society of the ‘50s and early ‘60s and in its outraged, disgusted pages we discern Kesey’s mission – as Ken Babbs bellowed at me: “the institution will be institutionalised and the patients will be free!”. For Kesey and The Pranksters, the individual, and their liberation, was everything - liberation from the death-grip of the sclerotic, reasonless social system, its immoral demands, its grim repressions; liberation from your own incarcerated consciousness, your submerged shame, your coerced sense of duty to everything other than yourself. Liberation as a gift, delivered painlessly without struggle, in a clear bloodless drop of liquid, a sacrament for you fallen, offered to your outstretched tongue.

Ken Babbs: “About sixth months [after the experiments] Kesey was working at that hospital and he was on the same floor as where he was when they were doing the experiments, and the doctor’s office was right there, and the door was open, and Kesey went in through the doors and there was a bottle of Sandoz pure LSD…”

Kesey swiped the acid and abandoned writing, “I’d rather be a lightning rod than a seismograph”, he said. The Pranksters clambered aboard their psychedelic bus and set out on the open road, resolved to liberate America one dose at a time.

For the Pranksters the bus was a Starship Enterprise, a vessel floating through the scattered galactic wastes of the twentieth century, in search of the coming consciousness. At the wheel sat the crackling presence of Neal Cassady, a shirtless monologue, spooling out anecdotes, asides and advice to no-one in particular, his mouth and eyebrows twitching erratically, like a smile caught on a damaged video tape, jerking through the static, jerking-repeating, jerking-repeating, while the highway screamed towards him, and the bus chewed it up.

A decade older than Kesey, and a couple of decades older than many of the Pranksters, Cassady was a legend in the burgeoning American Counterculture. He belonged to the Beat Generation, a group of writers and artists that included Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs and which had emerged in the dog days of the second world war. The Beats, defined by Kerouac as “beat, meaning down and out but full of intense conviction”, rejected the dominant post-war culture of conservative, capitalist materialism and the consumer society. They were interested in the perimeters of human experience, the liminal zones, transgression; they experimented with sex and drugs and explored spiritualism - the Eastern religions that have for decades made an idiot of every rich Californian were first imported by the Beats.

All of this of course took place in the basement of the 1950s; the straightened, heavily policed corridors above criminalised such behaviours and the Beats were generally regarded as deviant, profane. They were (and are) often misunderstood as Leftists, which they were not. Although their critique of society included capitalism, they are better described as libertarians and individualists, their revolutions introspective and personal. Rather than seeking to change American society, they were content simply to drop out of it.

An elusive, symbolic figure, Neal Cassady appears repeatedly in Beat literature, most famously as “Dean Moriarty”, the central character in Jack Kerouac’s On The Road. He was something of an itinerant drifter, a bi-sexually voracious hedonist who chased his muse and appetites in defiance of law and morality, a hyperactive chorus whose tumbling, mystifying verbiage was desperately recorded by his peers and entered posterity in some of the most important writing of the twentieth century; “a new kind of American saint”, Kerouac called him.

After Cassady moved to the Bay Area in 1954 many of the Beats relocated from New York’s Greenwich Village to the North Beach district in San Francisco, where their ideas spilled onto the city’s substrata. Together, Cassady and Kesey erected the bridge between the Beats and Hippies; Cassady, the implacable spirit of pure being, who rejected all injunctions other than those of the individual consciousness, its inclinations and caprices. Kesey, self-described as “too young to be a Beat, too old to be a Hippie”, who wanted to detonate Cassady on America, with a drug to liberate everybody’s inner Neal.

The collision of these forces, and their gathering of the Pranksters, would ultimately beget the Counterculture, but even in those blissful early days there were signs of trouble that no-one wanted to be honest about: “Neal is, of course, the very soul of the voyage into pure, abstract meaningless motion”, William Burroughs said of Cassady, “he is The Mover, compulsive, dedicated, ready to sacrifice family, friends, even his very car itself to the necessity of moving from one place to another”. Cassady’s fifteen-year-old wife LuAnne was less florid: “Neal will leave you in the cold anytime it's in his interest”.

Randle P. McMurphy, Kesey’s protagonist in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, is another such free spirit, a mixture of heroism and insubordination with a lengthy record of fighting and fucking that attests to his unrepressed, authentic naturalism. “Maybe that makes him strong enough, being what he is” observes the book’s narrator, Chief Bromden.

McMurphy’s story is one of martyrdom. As the novel progresses he gradually becomes a vessel for the aspirations of the other characters, and eventually sacrifices his life for their freedom. It is, though, a redemption story that contains an uncomfortable tension: as the critic Gary Carey observed, McMurphy dies not to redeem his own sins (and those of the other patients, his “disciples”) but rather to deliver the patients from their victimhood, from sins perpetrated against them by society.

It is this type of uncritical self-justification that makes McMurphy and Kesey’s revolution a particularly American one. There is an attempt to address collective salvation, collective improvement, self-sacrifice in the interests of the greater good that resembles the struggle of the Marxist Left, but the engine of social change is imagined not as class struggle, but as individual liberty. Liberty in which the individual is not required to reflect, atone, improve or demonstrate responsibility, but is simply required to “be what he is”. Liberty in which duty to others stretches only as far as a duty to this idea: that collective liberty secures individual liberty, and that in the tension between individual desire and the collective good, it is the collective good that will submit. It’s an uneasy alliance, one which reflects the obsession with religion and freedom that suffuses the American consciousness.

The Pranksters’ road trip eventually wound its way back to the Bay Area and Kesey’s sun-dappled home beneath the Redwood trees at La Honda. There they got the revolution started, disrupting the bucolic serenity with riotous gatherings of freaks, drop-outs and utopians that they called “The Acid Tests”, it was time for the patients to be free.

The Acid Test

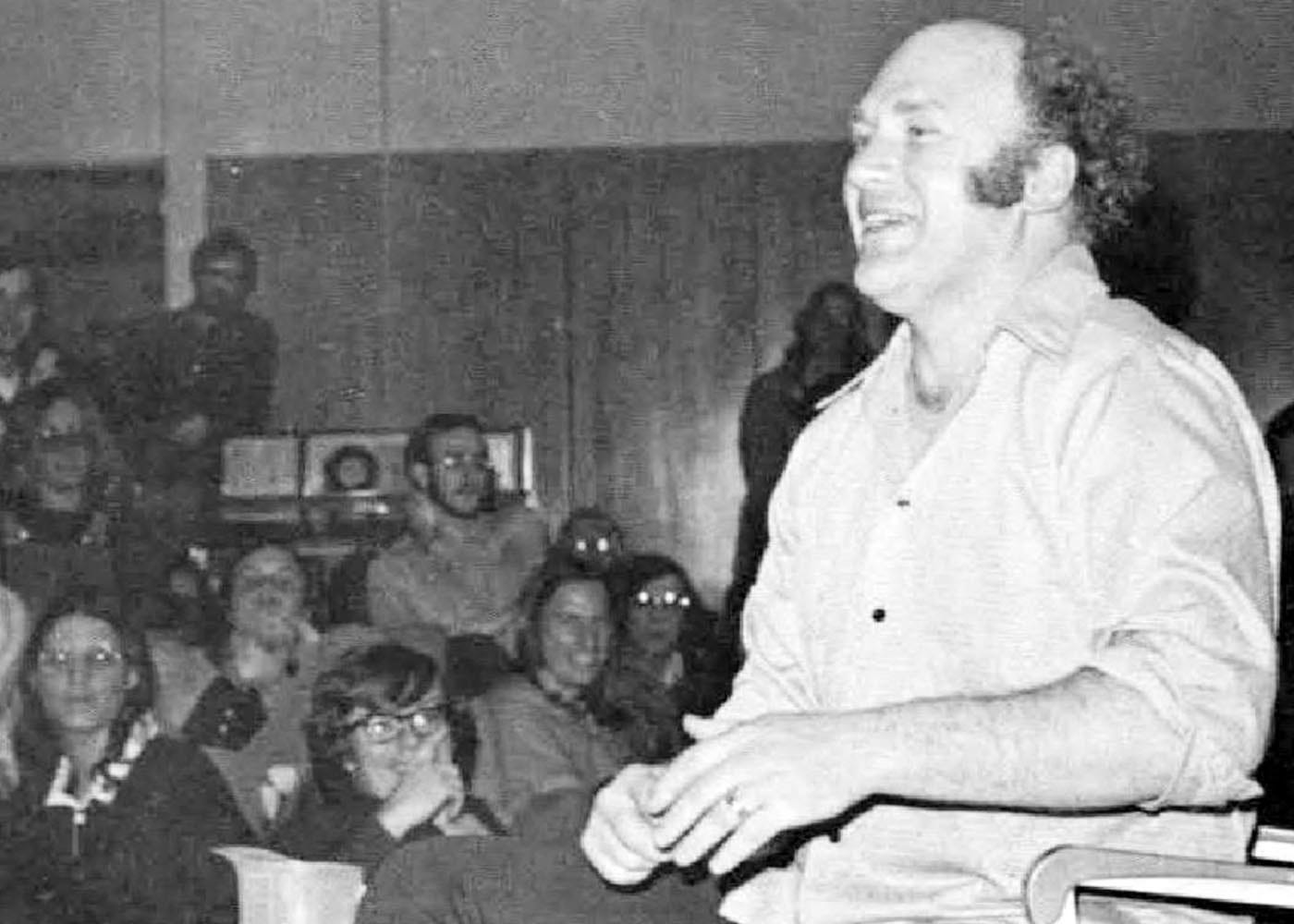

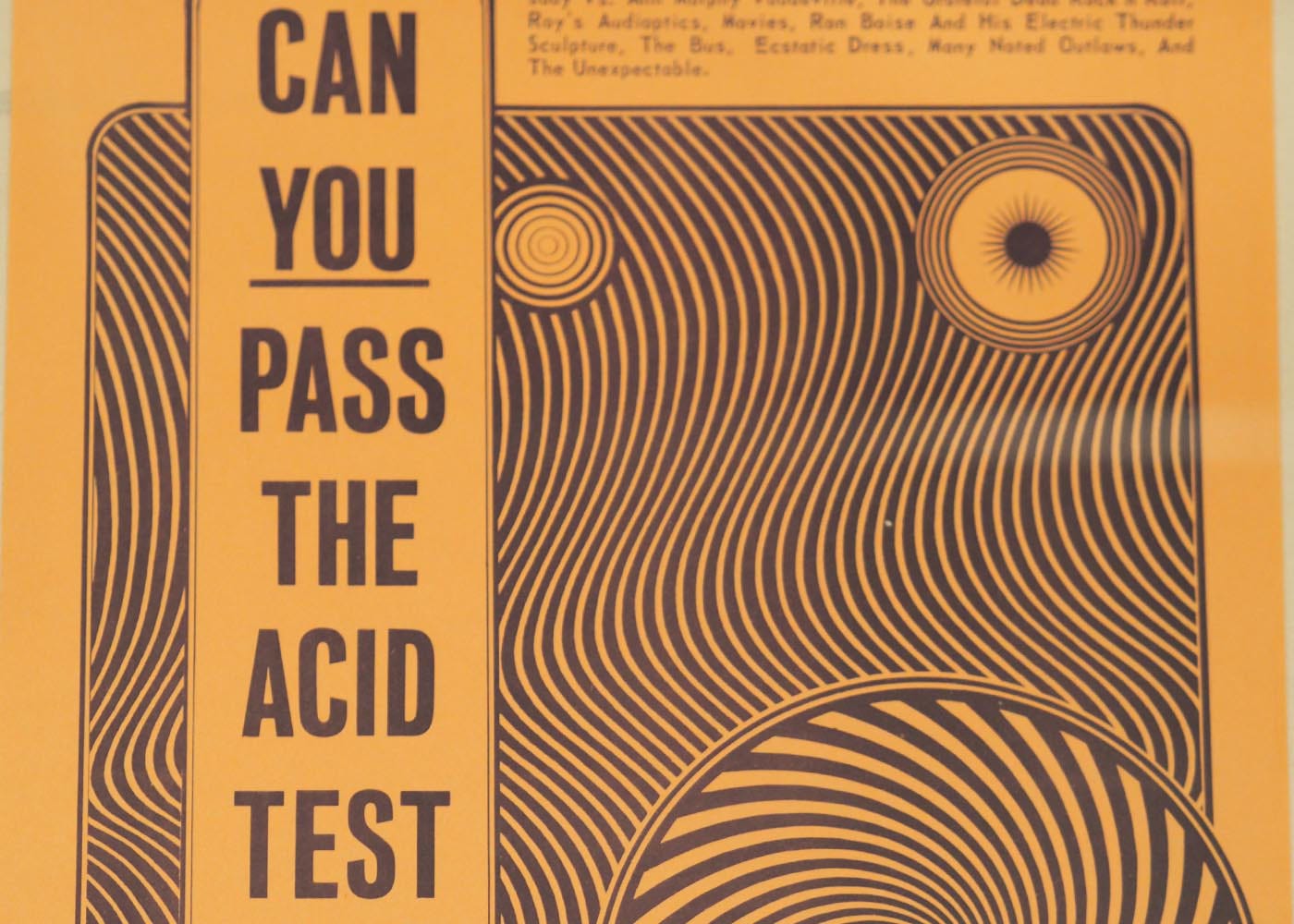

Back to the stifling Oregon heat and faded psychedelic swirls that climb and swarm over Kesey’s bus. There is a fat hornet that has been navigating Ken Babbs’s shirt for some time now and I have been trapped in anxiety, knowing that I should alert him, but not wanting to cut him off – it’s all good material. Eventually the hornet reaches Ken’s hand. “Wah” screams Ken, lifting from his seat, “eeeeeeee”, he flaps his hands above his head before collapsing back into the chair and issuing a series of thick, gulping chuckles “urgh huh huh huh huh”. The sloppy grin returns. “The Acid Tests”, I remind him. Ken picks it up: “We called it The Acid Test – ‘Can You Pass The Acid Test?’ – and we had little Acid Test cards made up. Because it cost you a dollar to get in and then you got your card, and then the next time you came it cost you a dollar, and if you didn’t have a card you could buy one for a dollar”.

The Acid Tests were a psychedelic Check Point Charlie on the border of the ‘60s, the full-colour, “swingin’’, freaked out and stoned, ménage à trois ‘60s, that is, the “kill your parents” ‘60s, the ‘60s that young people in the US and Western Europe were heading into, while monochrome helicopters and middle-aged professionals air-lifted the ‘50s.

They were nocturnal bacchanals held at houses and venues across the Bay Area, people often came in costume, faces painted, crazy wigs. American flags were everywhere, sometimes hanging from the rafters, sometimes pulled around the shoulders of a babbling freak, face crowded with painted stars - the references to America feel both ironic and insistent, the land of liberty, the future.

Everyone in attendance was soaked in acid and communed with one another in a vortex of clashing sound and light. Cassady, shirtless as always, sometimes presided, twitching and jerking, his eyebrows dancing, his mouth running. Film footage of the “Further” road trip was projected onto a wall, images of the Pranksters dancing and jumping around perplexed locals in some dusty mid-west town. There were candles and light shows, inks dropped onto overhead projectors that sent flares of overlapping, coloured light out into the darkness. Tech heads amongst the Pranksters engineered throbbing speaker stacks and experimented with tape loops and shuddering, disorienting soundscapes. Above it all the house band, The Warlocks, who would later rename themselves The Grateful Dead, belted out electrified RnB.

Ken Babbs: “What we tried to do was have two stages, one at each end, two music scenes. The Grateful Dead and The Pranksters would be at opposite ends, sometimes they’d play, sometimes we’d play and sometimes we’d all play together.”

Grateful Dead manager Rock Scully: “Band members, loosely called ‘the band’, could kinda wander off into the crowd and do something else.”

Ken Babbs: “It was really free-form and people would come and they would do their stuff as well, y’know? There was a whole movement in the Bay Area there, the psychedelic wave had hit.”

Disorganised chaos was the essence of the Acid Tests. “There was no ‘show’” Dennis McNally, The Grateful Dead’s former PR guy, tells me. “Everybody in the room was the show, you were the show, or the show is you. Whatever you did was the show”. This last remark catches my attention immediately, it seems to strike at the heart of the matter: the new movement, the hippie movement, was one born of pure solipsism; perhaps unsurprising, given the foundational role of drugs.

The Acid Test represented a kind of Spectacle of The Self, the synthesis of solipsism and spectacle. In this spectacle, performance is no longer a temporary act, aimed at some short-term, discrete end like entertainment, but is a permanent state of being, the self is self-consciously constructed and represented, or even misrepresented, at whim – “you are the show”. Insofar as an audience is acknowledged, it is as a participant in the spectacle, that is to say, any spectacle demands an audience in order to be a spectacle, but in this case the spectacle is not for the benefit of the audience but is a purely self-indulgent exercise staged for the edification of the performer. There are no concessions to the audience, the approval of the audience is unnecessary unless the performer feels it to be necessary, unless the performer wants approval which, when operating within this type of egomania, they often don’t, as the unintelligible madness of the Acid Test proves.

These were individuals concerned with asserting their individuality but doing so in the same room as a lot of other people, perhaps that was the radical thing - what looked like a shared, communal experience was actually a spectacle of extreme narcissism. It embraced early, inarticulate experiments with various concepts of identity, and I’m certain that the effort to reinvent society by freeing the libidinal impulses of the individual during a group acid trip was incredibly exciting. If this is what political action in the new America looked like it’s not hard to see how it was able to recruit immediately and widely, I’ve been to political meetings aimed at sincerely effecting incremental social change, with earnest discussions around labour rights and tax policies - they’re dull.

And so The Acid Tests culminated in The Trips Festival, three nights of drugged-up mania that profaned the distinguished chambers of San Francisco’s Longshoreman’s Union in January 1966, and which Ken Kesey co-produced with the proto-Hippie Stewart Brand (a recurring figure within the histories of the Counterculture).

Greatful Dead PR & Biographer Dennis McNally: “The last of the acid tests is part of the Trips Festival - three days, 5,000 people a night at Longshoreman’s Hall in San Francisco. So we’ve gone from 30 people to 5,000 in two months, this was a cultural mojo the likes of which no-one had seen before or since. 5,000 people tripping? After a while it became obvious that the police were going to take an interest, but there was nothing they could do – they weren’t violating any laws.”

Although acid was legal and the cops were powerless to disband or arrest the alarming hordes of tripping freaks, the festival proved to be a last hurrah for the Pranksters. Later that month, the closing heat engulfed Kesey. Having already faked suicide and skipped to Mexico, he was finally outrun by the FBI, who bundled him to the floor of a San Francisco jail house on Marijuana charges. LSD was outlawed before the end of the year. It didn’t matter, Kesey’s work was done. The Trips Festival was covered by both Time Magazine and Newsweek, the psychedelic wave was washing over America, the Hippies had arrived and a generational struggle for the American future began.

Next — Lessons From The Counterculture Part 3: Hippies & Angels

Reading:

Ken Kesey - One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest

Martin A. Lee & Bruce Shlain - Acid Dreams

Tom Wolfe - The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test

Dennis McNally - A Long, Strange Trip