Lessons From The Counterculture Part 4/9: The New Progressivism

The uneasy alliance between the Left & the Hippies

Note: this series is intended to be read in sequence, and this part makes references to personalties and concepts developed in the preceding parts.

“The so-called Counterculture of the 60s was divided into two parts. It had its religious part and its political part. The religious part was much bigger than the political part, say two to one, three to one. Hippies were the religious part. The so-called ‘Movement’, the Left, was the political part.”

-Robert Christgau

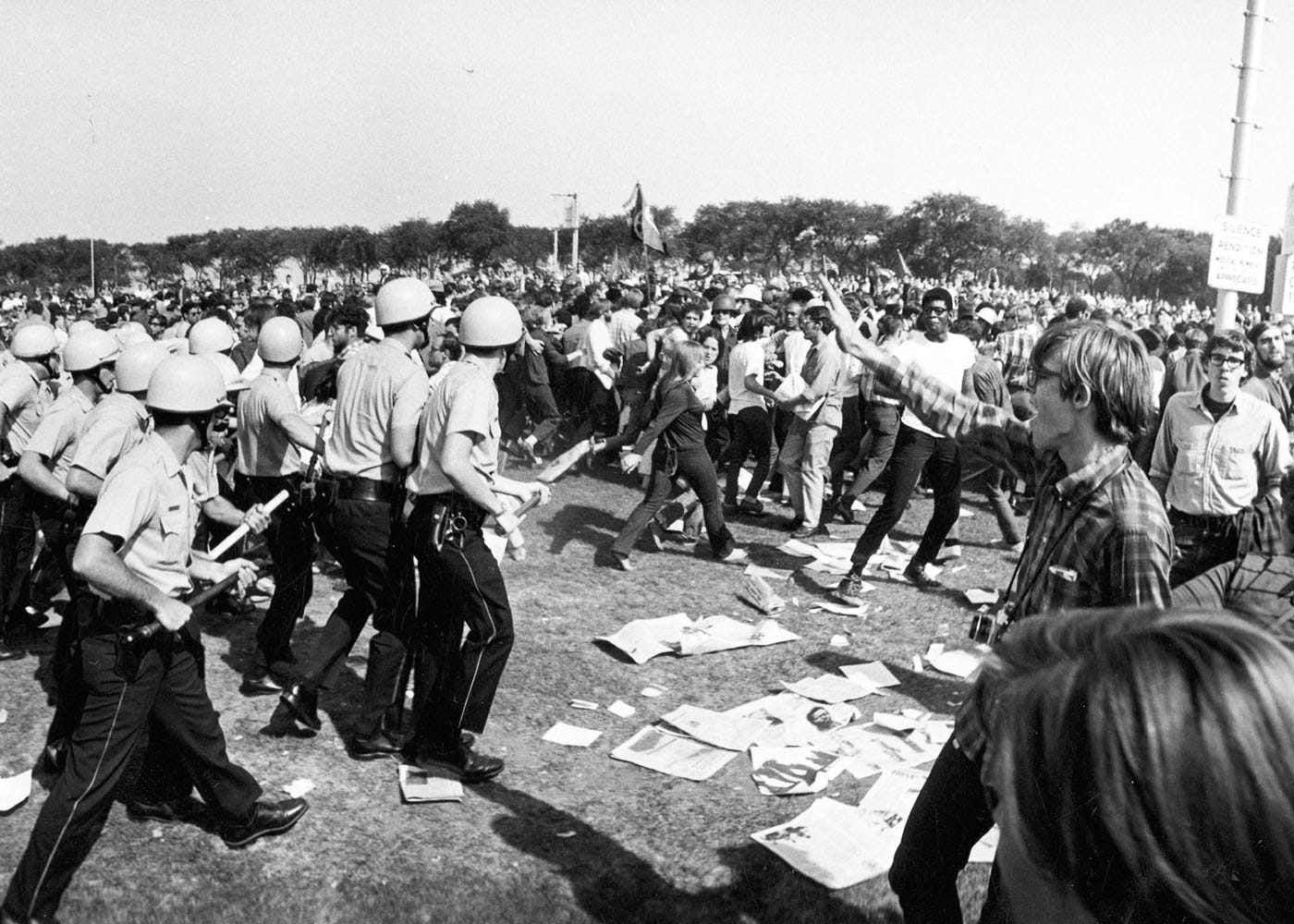

Chicago, 1968

Heat converged on Chicago in August, during a boiling summer in ‘68. Heat that drifted up from the gleaming Mississippi river and the Tennessee plains that had swallowed Martin Luther King Jr. that spring. Heat shimmering over a hundred cities that burned in the riots that followed. Close, thick, L.A. heat in the kitchen of The Ambassador Hotel, where Robert Kennedy lay dying on the floor at midnight, having summoned his faithful to Chicago, and now they had all come to Chicago - the Black Panthers, the anti-war demonstrators, the student radicals, the Movement, the Left. And Chicago was all tumid with heat and blood and rage.

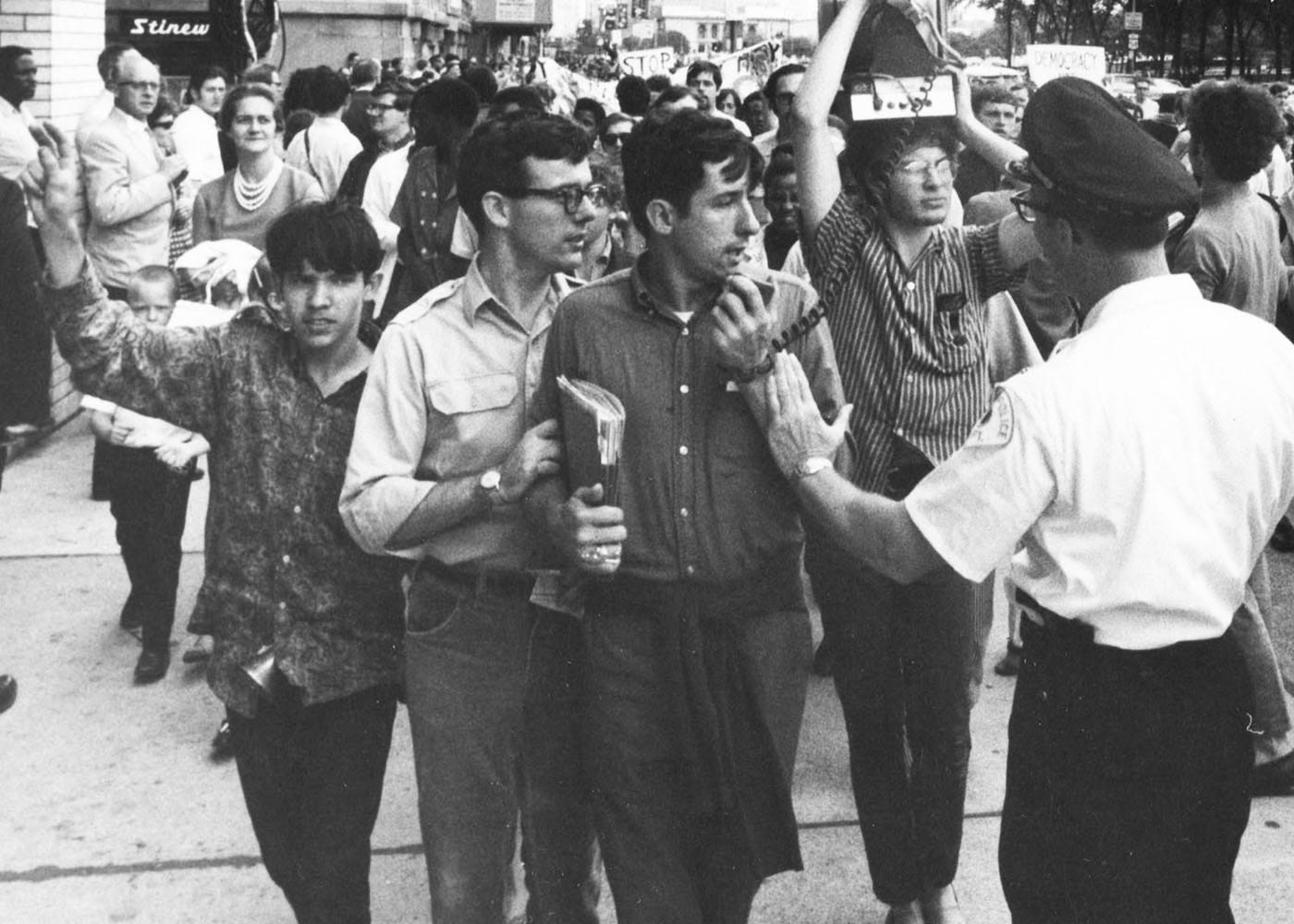

The 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago was the iconic point of confrontation between the Counterculture and the forces of reaction, in a city teeming with marijuana, marches, protests and the pyrotechnic state violence that a US National Commission memorably described as a “police riot”. After the columns of bloodied and wounded youth were triaged to the hospital or the jailhouse, seven anti-war protestors and Countercultural figures were tried for conspiracy and “crossing state lines with intent to incite a riot”. These were some of the most prominent leaders of “the Movement”, the coalition of politically engaged youth groups, student organisations, intellectuals and radicals that had spent the Sixties constructing a New Left in America, while the hippies danced consciousness and rattled tambourines on the periphery.

Among the accused were Tom Hayden, President of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and Director of the Mobilization Committee To End The War In Vietnam, and Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman, leaders of the Youth International Party or “Yippies”, a kind of political wing for the Hippie movement.

Tom Hayden had achieved notice as a twenty-two-year-old student at the University of Michigan. He was a sincere, practical idealist, motivated by a childhood terror of hell and abhorrence of the injustices, prejudices and immoralities visited by its agents. He combined a charismatic’s belief in a better future for mankind with a materialist’s understanding of diagnosis and cure; he was an intellectual and an activist.

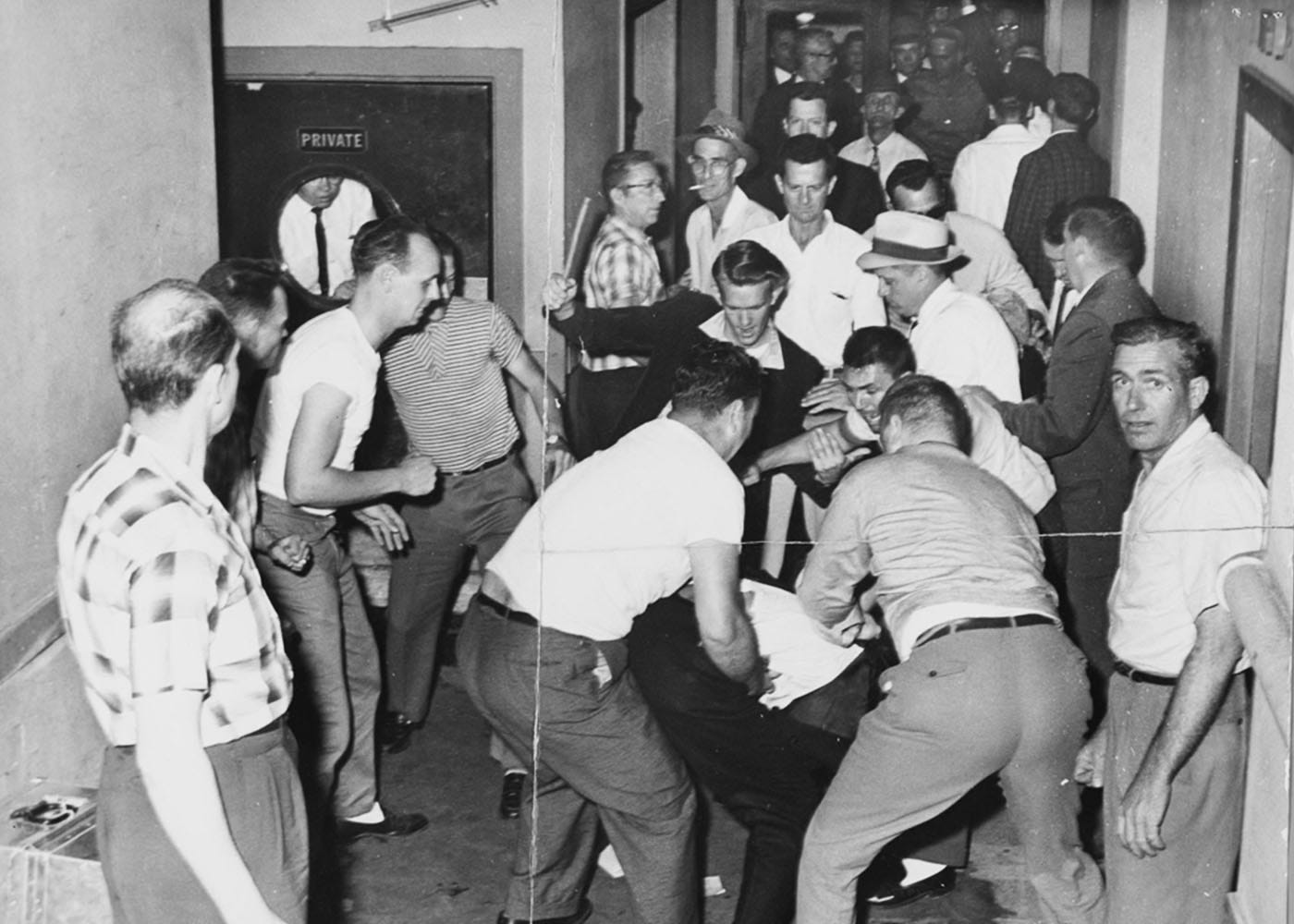

Hayden formulated his ideas in the infernal heat of Mississippi, while on the messianically titled “Freedom Rides”, a series of bus trips over the course of 1961 that aimed to break southern racial segregation by enforcing a US Supreme Court decision issued a year earlier, in which the court had ruled that segregating passengers travelling between states was unconstitutional.

The Freedom Rides came to act as a hazing ritual for the companies of youths that would enter the ‘60s Left: they were set upon by crimson-faced mobs of club-wielding Klansmen and police, who tirelessly dispensed fractures, lacerations and concussion as mankind’s better nature collided with its very worst. Hayden was an energetic volunteer for these beatings, and while recovering his senses in a Georgia jailhouse he started to compose what would become the manifesto of Students for a Democratic Society.

Students for a Democratic Society, or SDS, was inaugurated in 1960 at the University of Michigan as a successor to the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, an older left-wing student organisation founded by such distinguished names as Upton Sinclair, Walter Lippmann and Jack London. SDS’s initial significance was as the vehicle for student participation in the Civil Rights struggle, but in the summer of 1962 it articulated a more expansive political vision with the publication of the Port Huron Statement, a manifesto initially drafted by Hayden, and perhaps the founding document of the New Left.

What is immediately striking about the Port Huron Statement is that, in its description of the malaise and inertia that afflicted post-war America, it could be discussing the malady of Western societies post 2008 crash, with all the dislocation between the government and the governed, all the furies and disorders that have ensued:

“Politics today are organized for policy paralysis and minority domination, not for fluid change and mass participation… As man's own technology destroys old and creates new forms of social organization, man still tolerates meaningless work, idleness instead of creative leisure, and educational systems that do not prepare him for life amidst change… Automation, the process of machines replacing men in performing sensory, motoric, and complicated logical tasks, is transforming society in ways that cannot be fully comprehended”.

In fact, the statement’s themes correspond so directly to our present discourses that in reading it is easy to feel that no progress has been made at all. It is suffused with a biting anxiety over war and the prospect of nuclear conflagration, it perceives technology to be the implacable instrument of a borderless world, and abjures nationalism as the engine of war, it is anti-colonial, and critical of the cloaked projection of American imperial power, it is anti-racist, and feels that the issue of racial justice is one of the most urgent facing America, it warns of a crisis in mental health, it indicts America’s two-party system as unrepresentative and undemocratic. This in 1962. And aren’t we back there?

Although it would be wrong to collapse into fatalism over a lack of progress (there has been massive progress), it is certainly worth asking, given the Port Huron Statement’s diagnosis of the condition, what exactly happened with the treatment? Why did it fail to accomplish its aims? Why, in the grand scheme, did the 1960s conclude with Richard Nixon in the White House and base camp preparations for the ascent of the radical right, Milton Friedman, Regan and Thatcher? I think the answer lies partially in an ideological ambivalence within the New Left and partially in its relationship to the wider Counterculture and, in particular, to the hippies.

In contrast to the subversive contrarianism advocated by the Beats and the Pranksters, Students For A Democratic Society was at pains to outline a programme for practical political action within America’s existing political and civic structures. The students took inspiration from the gains of the Civil Rights struggle, which it saw as a form of praxis that could be expanded to encompass all areas of American politics. “Note must be taken of the Southern civil rights movement as the most heartening and exemplary struggle in this time of inactive democracy”, the Port Huron Statement announces, “it is heartening because of the justice it insists upon, exemplary because it indicates that there can be a passage out of apathy……the new emphasis on the vote heralds the use of political means to solve the problems of equality in America, and it signals the decline of the short-sighted view that "discrimination" can be isolated from related social problems”.

Indeed, the Port Huron Statement is directly critical of the peace movement and other “protest groups”, which it feels constitute nebulous organisations with conflicting aims. It accuses any movement that does not make itself felt within national institutions of being irrelevant and ineffective, it advocates instead for groups with overlapping or complimentary goals to unite and insinuate themselves into Labour unions, universities and the Democratic Party as the most promising vehicles for social change. Along with the standard Leftist critique of class and economic injustice, the Statement emphasises the need for broad political participation, greater democratic control over the economy, the “abolition of the structural circumstances of poverty” and enumerates the steps it perceives as necessary to “end the Cold War and increase democracy in America”. “If we appear to seek the unattainable”, it proclaims apocalyptically, “then let it be known that we do so to avoid the unimaginable”.

Yet for all its fastidiousness, all its insistence on building a political movement with dense foundations and solid construction, the statement is also home to a collection of ambiguities and contradictions that rattle around like misplaced screws on a workshop floor. Although the text hums with spiritual fervor, and regrets that “the retreat from ideals and utopias is in fact one of the defining features of social life in America”, its own utopia, its positive ideal for an American future, remains elusive: “We write, debate, and assert this manifesto, not as a declaration that we have the Final Cure, but to affirm that problems must be faced with an expression of knowledge and value, and in action… Our form is tentative—it will change as a response to growth”.

The cause of this flustered and apologetic evasion is, I think, the ideological ambivalence that I mentioned earlier, that is, an inability to confront and reconcile the ideal relationship between the individual and society; it isn’t quite sure of how to balance competing rights and interests, it doesn’t quite know how to approach the individual with both the gift of liberty and the demand for responsibility, or, as Isaiah Berlin formulated it, the proposition that “the liberty of some must depend on the restraint of others”, except in the most particular and unambiguous sense – that racist violence is unacceptable and must be stopped and punished, for example.

In attempting to draw the various countercultural factions that it derisively labels “protest groups” into a coherent and disciplined political movement, the manifesto of the New Left seems either troubled by the prospect of advocating for a society that might place demands on its constituency of supporters, who want to “break free of the 1950’s straightjacket” (and have no intention of being invited to pull on another one), or it genuinely doesn’t want to, in which case, there is no authentically Leftist prospectus, merely a Liberal one. Writing in 2007, the political journalist E.J. Dionne observed “The New Left in the 1960s was both powerfully communitarian and strongly individualistic…The Port Huron Statement, the New Left’s classic statement of principles issued in 1962, almost perfectly captured the era’s tension between individualism and community. At one point, it declared: “As a social system we seek the establishment of a democracy of individual participation, governed by two central aims: that the individual share in those social decisions determining the quality and direction of his life; that society be organized to encourage independence in men and provide the media for their common participation.” (author’s emphases).

There are a lot of smudges across Hayden’s manifesto, perhaps deliberately. Despite flicking between the words “individual” and “social” like a metronome indifferently marking time, the text never finds the courage to stop, and adopt a position on the role of politics in mediating the relationship between individuals and society. Perhaps this is because to do so is to head into a bewildering labyrinth - limitless, barbed passages of compromises, paradoxes and inconsistencies that often arrive at an uncomfortable destination.

The liberal democratic state invariably, inevitably, seeks to compose some balance between individualism, communalism and coercion, and this is where aspiring political leaders can be quickly swallowed in a dialectical swap. The Counterculture demanded liberty, demanded individual rights and denounced the carceral, bourgeois state of stale moral discipline and aimless production, yet the American Right, which controlled the state and which the Counterculture opposed, venerated freedom and individualism, at least on an ideological level; it promoted individual responsibility, private property, free markets, limited state intervention in the economy and limited state provision of social services. It was generally critical of communal organisations and initiatives - for example labour unions and social welfare programmes, which it accused of being coercive, and suppressive of individual agency.

But the real animus for these positions was, and is, always a communal one, that it is to say old-fashioned class antagonism. Political actors on the Right have through common endeavour constructed a vast metropolis of political groups, lobby groups, think-tanks and media organisations and pooled their considerable wealth in order to organise a collective defence of their class interests. When they advocate for liberty, it is not in the universal sense of liberty for all (as highlighted starkly in ‘60s America by the Civil Rights struggle), but simply in the particular desire to preserve the various individual liberties and privileges associated with the common membership of their class. And, again, with scant regard for philosophical consistency, they were and are more than happy to deploy the coercive power of the state in defence of those liberties, even while they denounce collective action in the form of strikes or protests as coercive and in violation of individual rights. They will almost always mobilise the legislative functions of the state to defend corporate interests over the interests of private individuals, for example.

The Left has likewise to wade through the same morass. What, in Michael Foot’s “great creed of human liberation”, is the role of coercion? When are the liberties of the individual circumscribed in the interests of the communal? Again the totemic programmes of the Left all energetically invoke coercive state power: land reform and public ownership – expropriation of private property; welfare programmes and social security – demands for a higher tax burden, and so on with civil rights legislation, equalities legislation etc. The Communist states of the twentieth century provide the salutary reminder that emancipatory movements can become so gratuitously coercive that in the extreme case the maniacal genocidaire Pol Pot, having exterminated two million of his fellow Cambodians, was able to stand before the stacked towers of their skulls and lament, bitterly, that “the line was too far to the left”.

Libertarians on both the Left and Right have a hard time acknowledging these paradoxes, often preferring to retreat into shallow mantras about maximum freedom, and it’s from this ideological vortex that perplexing hydras spring – weird political agglomerations that defy reason and with which democracies are a present struggling to cope: the bizarre libertarian-authoritarian groups that participated in the January 6th riots, the smiling New Age Spiritualists that demand the violent execution of Bill Gates and Anthony Fauci.

The ultimate ideological choice that must be made by any emancipatory programme is in how one confronts Berlin’s horrifying aphorism: “the liberty of some must depend on the restraint of others”. It is this confrontation from which the Port Huron Statement recoiled, if not with the same easily facility as Ken Kesey, happily propping up a San Francisco bar with the Hells Angels. It is a confrontation that Hunter Thompson ultimately had the substance to choose, a bloody lesson that should have served to make Kesey’s mind up for him.

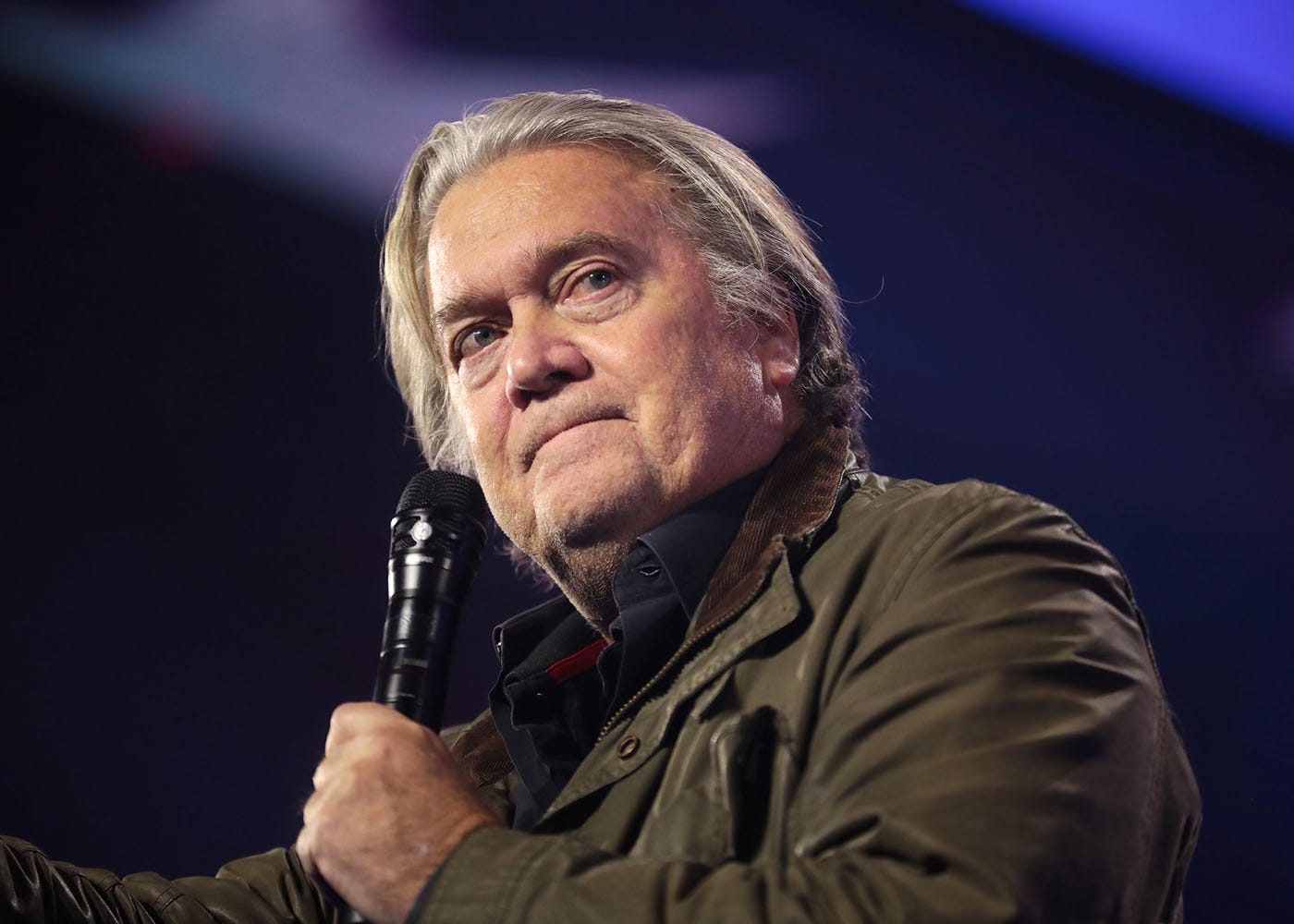

There’s a moment in American Dharma, Errol Morris’s 2018 documentary portrait of the Alt-Right superintendent Steve Bannon, (a film, by the way, that was reflexively denounced by the pious Left who witlessly abandoned the essential strategic principle of “know thine enemy” in order to howl about “platforming fascism”) which is revealing of this point of ideological departure.

Over the course of the film Bannon embarks on an impassioned castigation of the tarnished Neoliberal order and the iniquities that it has visited, with impunity, on the working class:

“Look at where the country is, look at working class people, look at where the middle class is, particularly from the financial crisis. People have been getting fucked. It’s as obvious as the nose on your face, we have a consolidation of power, we have a consolidation of wealth… you’re not going to earn anything, they’ve got you in this consumer environment where you’re always paying off your credit cards, they’ve destroyed thrift, so you can’t save anything – saving doesn’t make any difference. Digitally they’ve taken all your rights, they’ve taken all your personhood and they’ve written these algorithms that treat you like a hamster. You totally controlled. Absolutely totally controlled….you can’t fulfil your destiny…you’re nothing but a serf”.

These are sentiments that could have been quoted from the pages of the Port Huron Statement, or the slogans of the Occupy movement, or the speeches of Bernie Sanders, but Morris is a wise old hand, and throughout the film he seeks to cut to the chase: “but what good does it do to throw all of the darker people out of America? What good does it do to allow corporations to pollute the environment?” he demands of Bannon, “Is this populism? Or is this something much uglier? [It’s] serving big business and the rich. It’s anti-populism”.

What American Dharma illustrates is that both Left and Right can arrive at the same diagnosis, but that diagnosis is far less important than prescription, it is prescription that is the active zone of ideology, ambivalence on the part of the Left is the great opportunity for the Right, which will exploit an irrefutable diagnosis to obscure the mendacity of its appealingly simple, and appalling, prescriptions.

For the Right prescription is always easy, for the Left, it involves hard choices. This was the great dilemma for the New Left as it embarked on the road to ’68, and Hayden to the dock. Without an explicit vision of its destination, its prescription, how could it accurately know what “the Movement” was? How could it know whether its comrades in the Movement, the tumbling, laughing, arguing, protesting mass of bohemians, counter-culturalists, intellectuals, activists, students, drop-outs and contrarians were all fellow travellers committed to a unified cause, or whether some of them might represent something else entirely?

Whatever the liminal ambiguities, the fuzzy edges of the SDS’s programme might have been, the students did at least back talk with action and, energised by the successes of the Civil Rights struggle, embarked on the Economic Research & Action Project, or ERAP, a street-level programme to organise the urban poor that ran from 1963-’66 in a series of Northern cities including Chicago, Baltimore, Cleveland and Newark.

ERAP was in part a response to the incipient danger that the New Left’s vision of participatory democracy might become contaminated by identity politics. There was concern within the Civil Rights movement that the (entirely justified) focus on black emancipation risked alienating the white working class and, with ERAP, Hayden admirably sought to reconcile, rather than emphasise, racial divisions by building a racially diverse, class-based community movement that pre-empted Robert Kennedy’s ambition to “convince the Negroes and poor whites that they have common interests” – Hayden would later describe it as “organising the poor for power”. Backed by trade union finance, ERAP was able to deploy one hundred and twenty-five student volunteers into ten inner city projects where before too long reality bit, and hard.

Many of the student activists quickly tired of what we might call the “dog shit report”, the grey mundanity of small battles: chasing welfare claims and garbage collection, organising childcare, challenging the impunity of landlords or the local cops, negotiating with all the pressure and mental illness and casual violence and the thankless anger of the poor. This was not good grass and The Beatles, and sparkly-eyed young libertine sex beneath posters of Che Guevara. The project began to haemorrhage volunteers, who returned to university campuses to engage in revolutionary intellectualism and perform in the high theatre of anti-Vietnam War demos.

All this had been prophesised at the outset of the project by veteran community activist Saul Alinksy, to whom Hayden and his associates had been introduced by a supportive trade union leader. Alinsky listened to the students with complete scepticism, like a weathered old mechanic silently wiping grease from his hands, while some fearless young racer outlines his plans for a ground-breaking hot rod. They were, Alinksy felt, hopelessly naïve, with romantic notions of the poor and a misapprehension of the patient attritional work required to achieve enduring change. Sanford D. Horwitt, in his biography Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky, His Life and Legacy records of the meeting:

“‘Participatory democracy’, a central concept of the SDS Port Huron Statement, meant something fundamentally different to Hayden and the others from what ‘citizen participation’ meant to Alinsky. Theirs was something akin to the old town-meeting democracy, where everybody speaks his piece, consensus is the goal, and leadership and hierarchy are resisted, while Alinsky’s ‘organization of organizations’ put a premium on strong leadership, structure and centralised decision-making…While Alinsky himself was a harsh critic of ‘our materialistic, sanitized, Madison Avenue dominated society’, he was also adamant that effective organising had to begin with ‘the world as it is’ – and in the here and now, he told the young radicals sarcastically, what the poor want is a share of the so-called decadent, bourgeois, middle-class life that the SDS kids were so eager to reject”.

Hayden’s later regret at the failure of ERAP appeared to accept Alinsky’s analysis. Had the Left, he lamented, spent more time focusing on America’s internal issues, they may have been able to achieve the real structural reform that, ultimately, remained elusive.

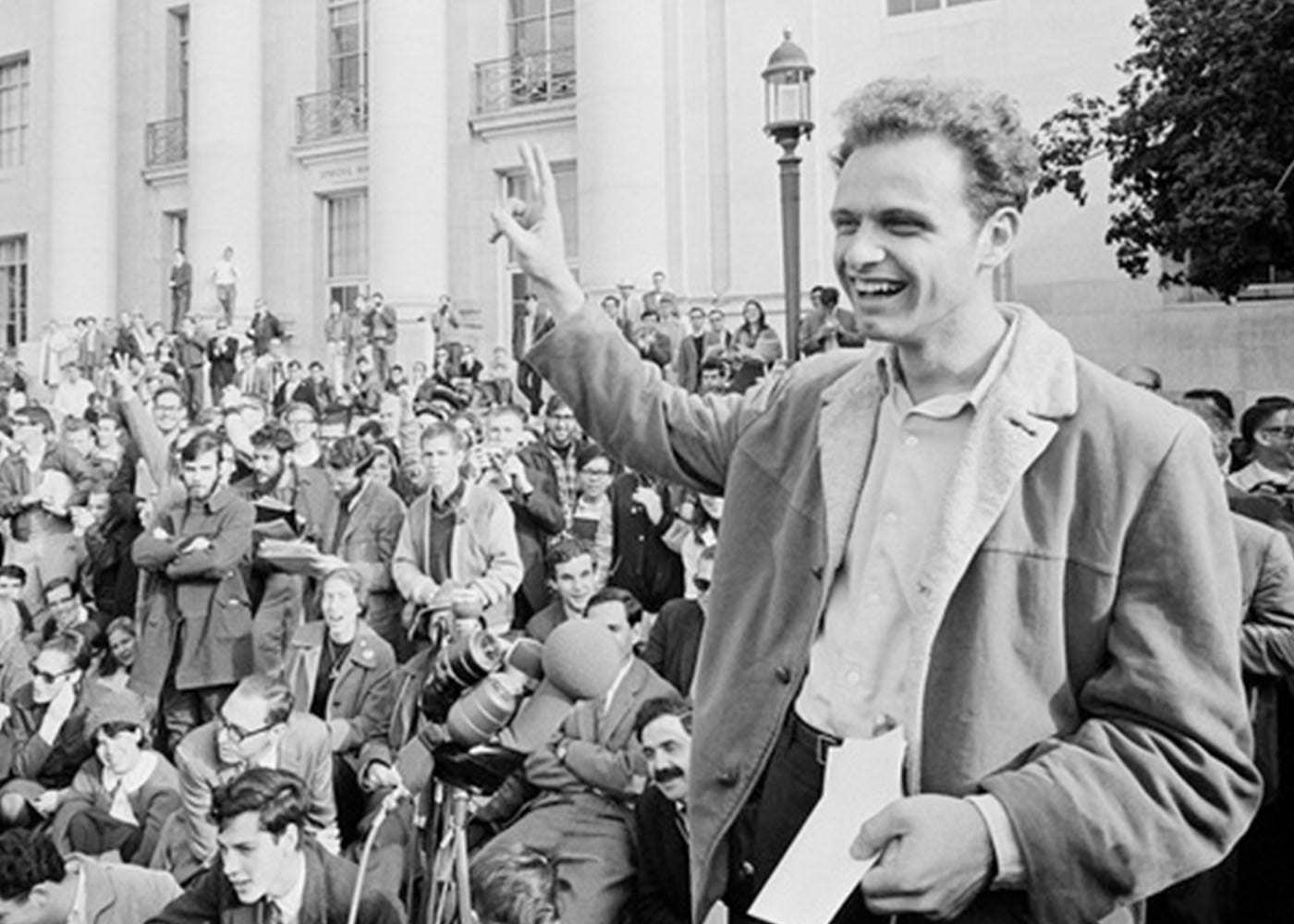

Still, in the early ‘60s the Civil Rights movement and the SDS had galvanised the nascent student Left, which began organising at Universities across America in furtherance of the political agenda described in the Port Huron Statement. In 1964 a mass rebellion of students broke out at the University of California at Berkeley, on the eastern fringes of San Francisco, after the Dean (a Colonel in the US Marine Corps) sought to ban political activity on campus. Led by the twenty-one-year-old Mario Savio, who exhorted a crowd of his fellow students with “there’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes one so sick at heart that you can’t take part, you can’t even tacitly take part, and you have to put your body upon the gears and wheels, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to stop it”, Berkeley activists launched the Free Speech Movement, or FSM, a long-running series of sit-ins and acts of disobedience in which thousands of students participated to demand the right to free speech and academic freedom.

The Free Speech Movement was a seminal moment in the history of the New Left, it forced the University hierarchy to capitulate, became a progenitor of the anti-Vietnam war movement and established Berkeley as the fountainhead of Counterculture protest in America. Its antecedents on our contemporary student Left would do well to mark what it struggled for – free speech and academic freedom, achievements currently jeopardised by their hysterical mission to censor, silence, “de-platform” and discipline.

A few months after the FSM’s victory, fifteen thousand young people marched against the war at the Berkeley Vietnam Day Rally. Organised by Jerry Rubin, a Berkeley drop-out, Marxist and activist who would later join Hayden in the dock, the rally was the point of fateful collision between the New Left and Kesey’s proto-Hippies. Martin A Lee and Bruce Shlain, in their outstanding history of the era, Acid Dreams, describe the scene:

“Kesey’s entourage, which included a number of mean-looking Hell’s Angels, grew restless while the anti-war speakers riled up the crowd about the genocide across the ocean….the lack of humour amidst all the self-righteous rhetoric rubbed [Kesey] the wrong way….he pulled out a harmonica and regaled the crowd with a squalling rendition of Home On The Range. ‘Do you want to know how to stop the war?’ Kesey screamed. ‘Just turn your backs on it, fuck it!’ And then he walked away”.

With this profane flourish did Kesey dismiss all of the Leftist neuroses to be discovered in the pages of the Port Huron Statement, the tension between the individual and society, the spiritual diffidence that yearned for an ambiguous return of “ideals and utopias”. For Kesey, society was nothing more than a tumultuous noise at his borders, unworthy of notice, and utopia a private matter, a state of being particular to each individual, if anything, utopia was an absence, a repudiation of the desultory limits imposed by history and externalities. “Kesey represented those elements of the hip scene that emphasised personal liberation without any strategic concern whatsoever”, write Lee and Shlain, “the task of remodelling themselves took precedence over changing institutions or government policy. This posture rankled hardcore politicos who were committed to busting the system that had driven them into limbo”.

Although “hardcore politicos” may have taken offence at Kesey’s flippancy (though usually not at his exemplary hedonism) there were many (perhaps a greater number) on the Left, including veterans of the FSM and refugees from ERAP, that found his permissive philosophy-of-self-centredness appealing, particularly if it offered intellectual justification to abdicate from life on the breadline, filling the index of the dog-shit report in some chilly northern ghetto.

Kesey received a hearing precisely because of that ideological ambivalence in the Port Huron Statement, the tension between individual/communal, that struggled for reconciliation and expressed itself within the embryonic form of the New Left. From Lee and Shlain:

“The young radicals were fashioning the beginnings of a unique political gestalt that encompassed a dual-pronged radical project. They believed that challenging entrenched authority entailed a concerted attempt to alter the institutions and policy-making apparatus that had been usurped by a self-serving power elite; at the same time they sought to lead lives that embodied the social changes that they desired. For sixties activists, the quest for social justice was in many ways a direct extension of the search for personal authenticity”.

It is revealing, in this formulation, that the “search for personal authenticity” precedes the “quest for social justice”. Social justice is a concept that should be arrived at, in my view, through an objective analysis of what constitutes fair treatment of individual actors within societies and the matrix of rights – economic, civil, social, legal – that serve to implement it.

Social justice should not be understood as a subordinate branch of subjective and libidinous desire, a “search for personal authenticity”. If the origin of the project is not to mediate between the individual and the social spheres, not to confront Berlin, but instead an expression of some benevolent impulse within individual desire, or the “politics of consciousness”, then the consequences are at best unstable and at worst destructive.

This is where the Counterculture began to emerge as an uncomfortable hybrid of these two tendencies: the quest for personal authenticity as personified in its pure form by Kesey, and the movement for systemic political change and social justice as envisaged by Hayden; it would be given form in the “liberated zones” of San Francisco, and go to war in Chicago, where, in the aftermath, Saul Alinksy re-appeared to walk the battlefield; Horwitt:

“One night Alinsky and the writer Louis Lomax walked across the street into Grant Park to talk to the students, many of whom felt defeated or demoralized. They had worked for [Eugene] McCarthy -or Bobby Kennedy- but even though their efforts had helped knock Johnson out of the presidential race, here they were being tear-gassed and beaten, while Johnson’s Vice President, who supported his Vietnam policies, was being nominated in the Amphitheatre. Alinksy was sympathetic to a point, urging them to go back home and begin organizing so that next time they would be in the convention hall wielding the power. But in the months that followed he was also highly critical of many student activists who, he felt, “aren’t interested in changing society. Not yet. They’re concerned with doing their own thing, finding themselves. They want revelation, not revolution”.

Next: A New America, the Liberated Zone.

Reading:

Tom Hayden - Rebel: A Personal History of the 1960s

Martin A. Lee & Bruce Shlain - Acid Dreams

Sandford D. Horwitt - Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky: His Life and Legacy