Lessons From The Counterculture Part 5/9: A New America, the Liberated Zone

How the Hippies dropped out

Note: this series is intended to be read in sequence, and this part makes references to personalties and concepts developed in the preceding parts.

“Social radicals tend to be arty…their political bent is Left, but their real interests are writing, painting, good sex, good sounds and free marijuana. The realities of politics put them off…they have quit one system and don’t want to be organised into another.”

-Hunter S. Thompson, The Nation, 1965

It’s a supernatural thing, that wall of fog that stalks across the bay before dawn, in the dream hours, severing the city from the rest of world, swallowing the bridge and its towers that grope up towards the clear air, pressing in on the harbour, the streets, the roads out, as if the whole place were under a sign. The first time I came to San Francisco, as a dumb eighteen-year-old riding in on the Greyhound bus, this happening amazed me, how that bright place all apple green and yellow under its pearly Western sky, marching pink, red and teal houses, the pacific sparkling away at the perimeter, would suddenly enter a shadow realm, the wooden houses drained of colour and slicked with damp; dark and grey-blue, the fog falling in from above.

That fog is like melancholy given form, reminding everyone that it’s there. It’s much easier to ignore when the streets are hot and bustling and there’s music in the park, but when the wet sets in and it’s dark and grey-blue, that’s when you notice just how many lost people there are in that city, what a truly staggering quantity of homeless people, more than I’ve ever seen anywhere else. People glassily wandering the streets with their stacked belongings, pulling wet nylon sleeping bags over their heads in the parks, crowding onto downtown Mission Street, outside the shelters and churches where they drink and laugh and cry and seethe.

The first time I went there, as that dumb eighteen-year-old, I walked for nine hours, something once possible before the cigarettes and drinking called it in. I covered as much of San Francisco as I possibly could, I scaled the hills around North Beach where Cassady, Kerouac and Ginsberg had lived, I visited the City Lights bookstore and sat in Café Trieste, where all the Beats had hung out, and I headed down to Mission, where I was staggered by the quantity of homeless people, and the misery and the deprivation, and I wondered why I had had no idea that this existed, this shadow zone, why it’s not something that is talked about in relation to San Francisco, why it’s all the peace and love stuff that gets happily mentioned, and not the casualties. I wondered whether free love, psychedelics and hedonism had some downsides, and then I thought about other things for the next fourteen years.

Back in San Francisco, this time with a rented car, I want to revisit those questions of downsides, what had happened to the Counterculture and the utopianism of the early-mid Sixties, why there seemed to be so much of everything that the Left was supposed to struggle against.

San Francisco bay was the delta into which all the boiling tributaries of the Counterculture flowed. It was where the Beats concluded their journey Westward and stared out over the vast reaches of the Pacific and into the sun, finally risen from behind the black horizon of the Great Depression, the world war, the death throes of Victorian morality. It was where Ken Kesey inaugurated psychedelic transcendence and spiritual freedom, where all the rock ‘n’ roll, light shows and dancing naked in the park happened, where the Left marched and burned draft cards and flung Molotov cocktails towards the rows of white helmets and rifle barrels, it’s where the religious side and political side pulled up their boats and talked about what the future might look like.

San Francisco, 1966.

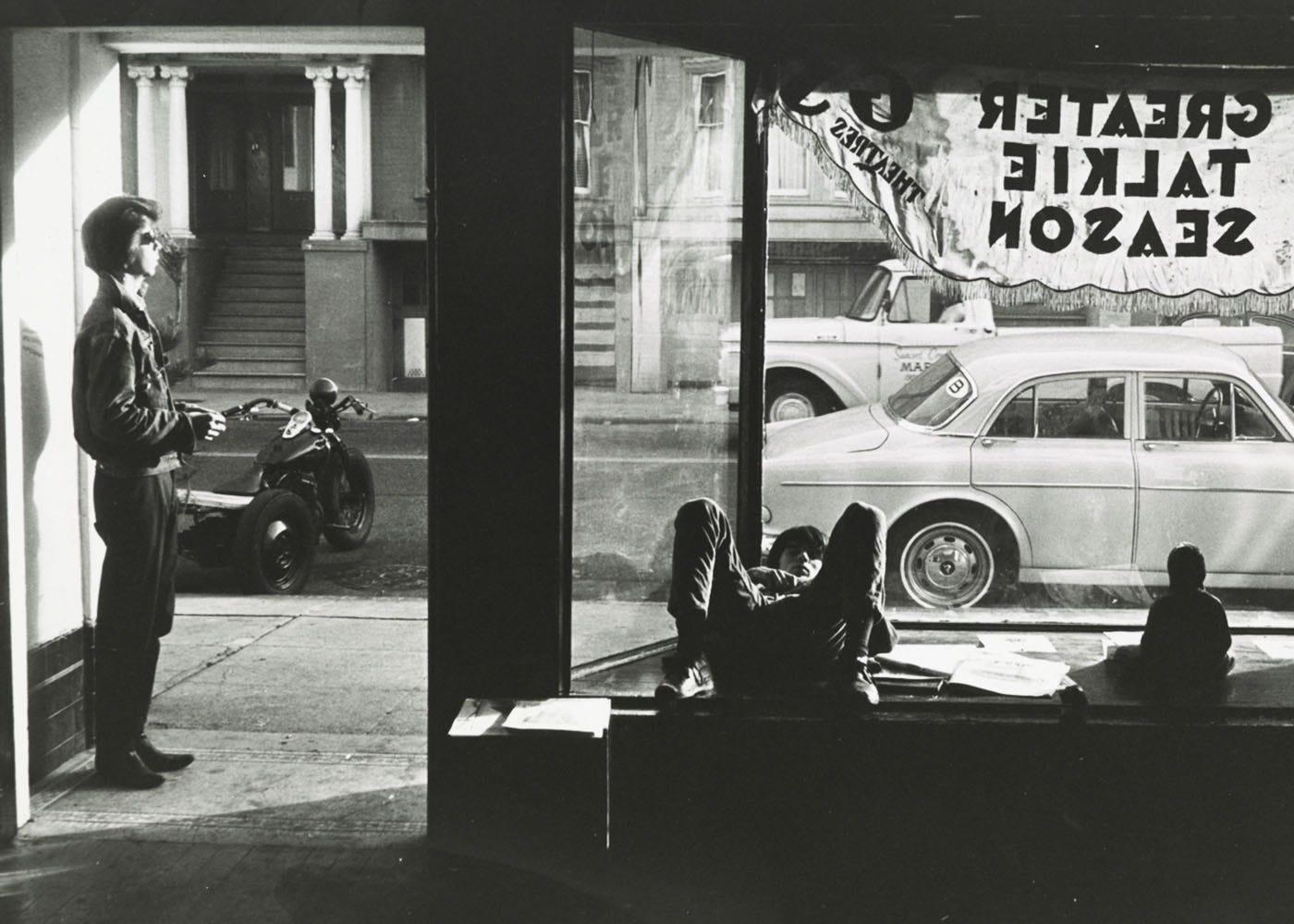

The flowers are in bloom. It’s like a permanent carnival, people in costume crowd the street: native Americans, top-hatted Victorian dandies, poncho-wearing desert-wanderers, railroad riding folk musicians, guitars slung across their backs. Streams of colour travel across windows, shop fronts, signs, clothes and faces, a great expanding mandala of red, yellow, purple, orange. There’s the throb of drums on the wind, people dance and get high in the park, while a band plays on the back of a flatbed truck. This is Liberated Zone Haight-Ashbury, a pocket of the city in which rents are cheap, and into which a community of young people have moved to pull off the “50s straitjacket” and act on Ken Kesey’s advice to “Just turn your backs on it, fuck it”.

Grateful Dead PR Dennis McNally: “[it started as a] group of perhaps three or four thousand people, most of whom made a living somehow connected with rock and roll. You didn’t need much money, it was simply possible to live on the margins and have a great deal of time to do what you wanted to do. They weren’t kids, they were people in their 20s, and they experimented with freedom – sexually, drugs wise, sensually, intellectually, artistically.”

Grateful Dead Manager Rock Scully: “It was a fellowship of people that were like-minded, had experienced something life-changing (LSD), giving us new ideas of how to look at society and how to live together, a very open minded community….everybody had a great idea about something and shared it, liberally, y’know?”

Anthony DeCurtis, Rolling Stone Magazine: “It became a model. The East Village in New York and college towns took on this Haight-Ashbury quality…there were these places that became free. “Liberated zones”. The idea was that we need to establish beach heads here for the new consciousness”.

Musician and Journalist Davis Gans: “They wanted to see if they could live without money, without materialism”.

The community in Haight-Ashbury completely rejected the New Left’s project to seize and remodel the architecture of the state. This was Robert Christgau’s “religious side” of the Counterculture, the hippies - successors to the Pranksters who had inherited the former’s politics of autonomy, introspection and hedonism. Christopher Hitchens described the phrase “The Personal Is Political” as being “a reaction to the defeats and downturns that followed 1968”, but the concept originated earlier, with the hippies.

As we shall see, insofar as that phrase encapsulates the eschatology of the Left after 1968, it is only because, by that time, the majority of the political side of the Counterculture had been finally devoured by the religious. In the early days, however, the spiritual release that the hippies had experienced through psychedelics moved them to disengage from what they saw as a dilapidated system of social relations in favour of self-actualisation within a community of like-minded individuals. Martin A Lee and Bruce Shlain, in Acid Dreams, write:

“By dropping out and joining the Haight-Ashbury scene, young people were not necessarily renouncing their commitment to social change. But they felt that the personal and the political could not be split into separate categories. Human liberation was something to be acted-out because it was right-on, a better way to live, rather than an item petitioned for during protest hour…The cultural renaissance fuelled by LSD…insisted upon a revolution that would not only destroy the political bonds that shackle and diminish us but would also, in the words of Antonin Artuad, “turn and face man, face the body of man himself, and decide once and for all to demand that he change.”

Looking back through archive interviews and vox pops with the aboriginal hippies, I’m struck by how consciously, and repeatedly, they emphasise this politics of personality, although they simultaneously reject, vigorously so, any attempt to describe it in political terms. When one of them tries to answer a baffled interviewer’s questions as to what their collective ethical scheme might be -“what are your principles? Do you have any?”- he is quicky censured by a companion: “we’re not trying to change anything, we’re just trying to be ourselves, man”.

The Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, a thoughtful, articulate figure who was generally more yielding in interviews of this type offers, “what we’re thinking about is a peaceful planet, we’re not thinking about anything else, we’re not thinking about any sort of power, we’re not thinking about any of those kinds of struggles, we’re not thinking about revolution or war or any of that. That’s not what we want. No one wants to get hurt, no-one wants to hurt anybody. We would all like to be able to live an uncluttered life, a simple life, a good life. Like, think about moving the whole human race ahead a step or a few steps”.

Indeed, listening to the hippies themselves, it’s tough to infer any political attitudes beyond John Stuart Mill’s broad defence of negative freedom and the thin liberal aphorism “do no harm”.

This attitude is superficially admirable, and attractive – the Haight was very cool. The neighbourhood began to assemble its own economy and community infrastructure, which channelled the radical hippie ethos of free-expression, psychedelic drug use and the particular strain of Communal-Individualism that had appeared during the Beats and Prankster eras, with a heavy emphasis on music and experimental art.

There was the Psychedelic Shop from which to score acid; an underground newspaper, The Oracle, which disseminated news, art and esoterica; a tall, shambling house inhabited by the Grateful Dead that became the unofficial headquarters of the scene, and the ballrooms, The Fillmore and The Avalon, in which the bands played, audio engineers experimented with speaker technology, visual artists created light shows, and ardent young hippies dropped acid and moved, something previously unheard of at music concerts, flinging and twisting their limbs through an iridescent miasma of light, sound and hallucination.

Despite the effort on the part of the hippies to resist political classification, it’s perhaps useful to think about the early Haight, this “loose community of free individuals”, in relation to the Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci’s concept of “Cultural Hegemony”, which holds that the system preserves itself by dominating culture to present its own ideology as the only legitimate worldview.

Rather than challenge the system on a structural level, through the institutions, as the Left advocated, the hippie project represented a kind of exemplary response to Cultural Hegemony in America; in articulating an alternative culture, the Haight would expose the latent Cultural Hegemony of the state, something that mainstream society would find impossible to ignore.

This was not necessarily conscious on the part of the hippies – consciously, they thought that the best way to explode cultural hegemony was to drop acid – but it does help to explain why they felt that “dropping out”, personal transformation and an alternative mode of living was a sufficient response to a social order that Lee and Shlain describe as being “pervaded by a sense of daily apocalypse”.

It’s notable that in our contemporary politics, also “pervaded by a sense of daily apocalypse”, Gramsci’s lessons have been well learned by those on the radical Right, the most thoughtful of whom are always enthusiastic students of Marx. Steve Bannon, in particular, has taken good note of the Counterculture in exploiting both traditional and new media to mount a panoramic assault on those aspects of post-war liberalism that he perceives as representing liberal Cultural Hegemony in America and Europe: he describes his project as “flooding the zone with shit”.

It's a project that has been joined on a supranational level by Vladimir Putin, who has deployed endlessly proliferating bot farms, client media organisations and credulous political proxies across the world as part of an effort to undermine both global and regional institutions (the UN, the EU) and destabilise Western societies by mounting and amplifying attacks on post-war Liberalism. This is the engine room of our Culture Wars, with blackened characters like Bannon busily sweating away down there, shovelling coal into the furnace, and is yet another warning, for anyone moved to engage in these conflicts, that you had better consider whose game you’re playing. Those forces looking to break Western Cultural Hegemony are clear in their motivation, well-organised and lucid about what they want to build in the breach; the Left had better be able to say the same.

The spectre that haunted the Haight was not a presence, it was an absence; the absence perceived by Hunter S. Thompson when he said “they have quit one system and don’t want to be organised into another”, the absence of leadership and organisation, of positive vision other than to endlessly replicate the hippie politics of euphoria: “taking drugs was a way of saying “No!” to authority, of bucking the status quo”, write Lee and Shlain, “(they) thought they could elevate the world simply by elevating themselves…that massive change would only come about when enough people expanded their consciousness”.

This was the type of tenuous system of ethics, with Libertarian concepts of individual freedom at its summit, that had been at work in the Merry Pranksters’s profoundly unattractive blend of solipsism and moral relativism. Here it was again, applied as the founding ethos behind a new experiment in community; who, this time, might the hippies leave in the cold if it suited their purpose? But, in the mid-60s, these depressing portents did nothing to disturb the hippies’ trip, they genuinely felt that the art, sex, dope and music would elevate humanity, and that Eden could be recovered through ecology, community and good intentions.

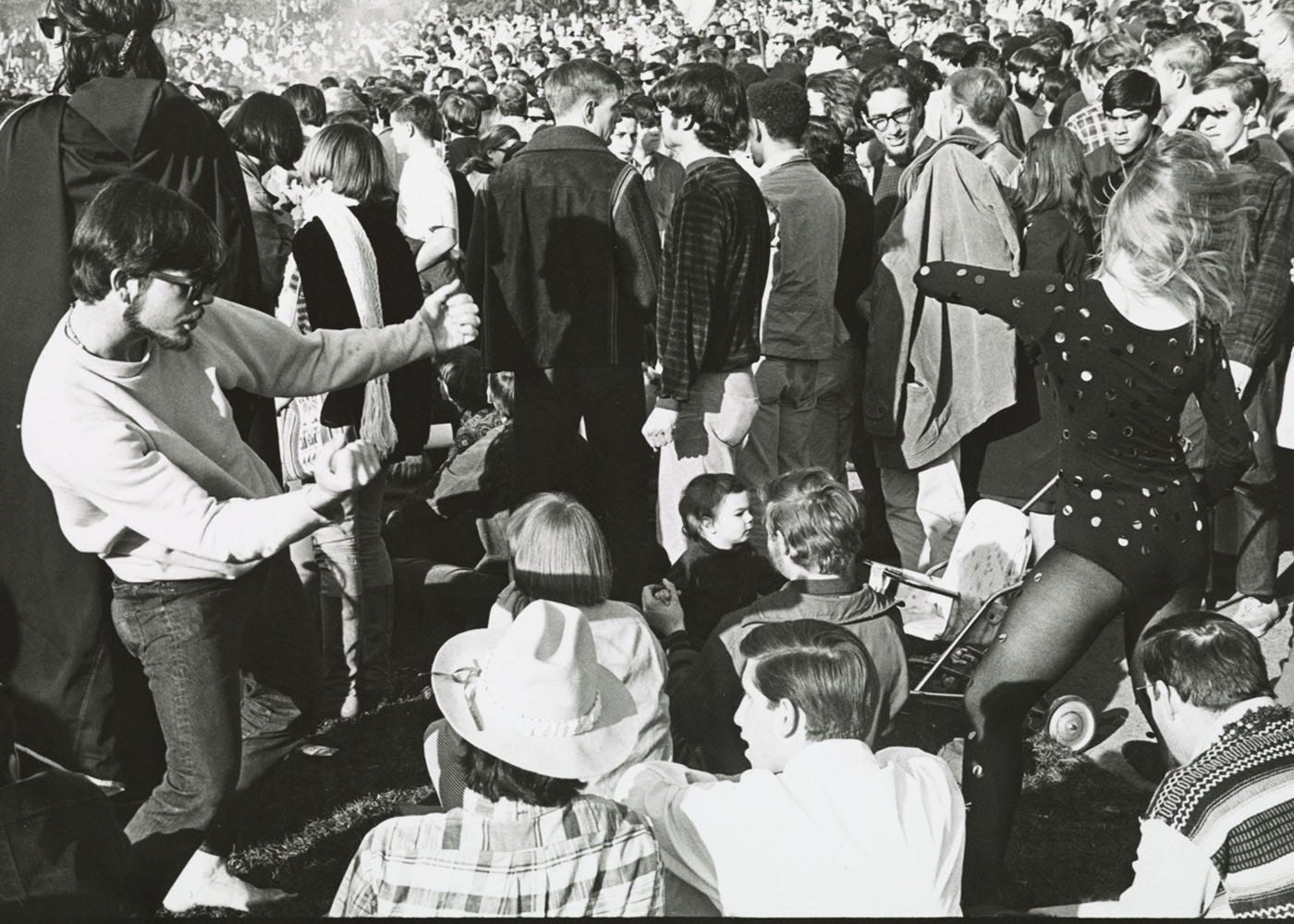

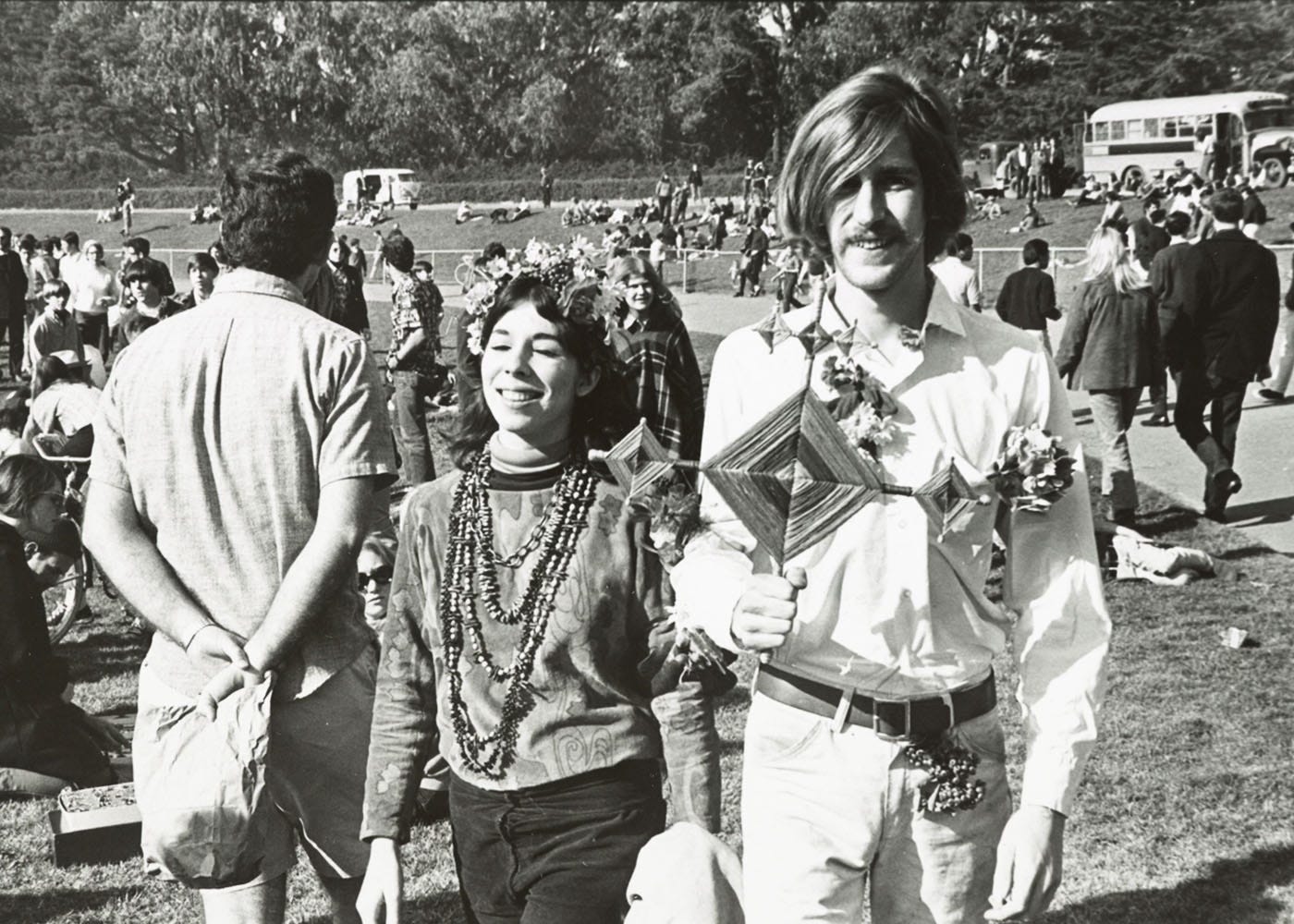

In the opening weeks of 1967 Haight-Ashbury’s luminous eddies washed into San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park for the “Human Be-In”: 20,000 tumbling, dancing, tripping hippies waving flags, banging drums and chiming bells, faces painted with petals and the word “love”, The Grateful Dead high and heavy between towering speaker stacks, Allen Ginsberg leaping up and down in a dazzling white Kaftan, Timothy Leary, flowers pushed into his greying hair, exhorting the brilliant shifting mass to “turn on, tune in and drop out”.

This was the “gathering of the tribes” the great solstice for the politics of consciousness, there was something religious revivalist about it: change your mind, in this case through psychedelic drugs, and you’ll change the world.

Rock Scully: “We had some sort of conception of how far reaching this went, but we thought we’d celebrate each other – everyone who had been turning on over the last year or two. A bunch of us thought this would really be a cool thing, let’s see how many there are of us and see if we can spread the word and have a day to ourselves out in the park. We’d put up a bandstand and get all the bands from San Francisco to come and play it, and the word started spreading, just word of mouth, we had no idea of how many people were going to show up. It was an amazing, amazing experience because it kind of gave us a grasp of how widespread this had gotten”.

The Be-In brought the hippies to the astonished attention of the national media, which recognised that a significant cultural rupture had appeared on the West Coast of America and scrambled to understand what this might mean in political terms. They quickly found that, whatever the answer to this question may be, it would not be produced by the hippies, who giggled inanely into the microphones of bewildered news reporters, and talked about “howling at the noonday sun”.

This declinist attitude towards politics on the part of the hippies was the broad counterpart to the humourless moralising of the New Left that had exasperated Ken Kesey at the Berkeley Vietnam Day Rally, and where Kesey’s interventions at that event had “rankled the hardcore politicos”, it was now the turn of the hippies to find themselves fraternally irritated by the politicos. The energy and organisational achievement of the Be-In was naturally attractive to the Left at Berkeley, and the most prominent of the student leaders, Jerry Rubin, sought to broker some time on stage in which to inflame the passions of the crowd and arouse the youth to revolutionary action; the hippies were not having it.

Rock Scully: “Berkeley wanted to get involved really badly. The activists, the radicals all wanted to come and speak at this thing and we said ‘this is not for speaking, we’re not going to do that. We’re going to have some prayer ceremonies, we’re going to do the native American blessing, Allen Ginsberg is going to teach us how to breathe, and get high that way, and Jerry Rubin – you can have three minutes’”.

Robert Christgau: “The Berkeley Left tries to get these people to do political stuff and provide a forum for their speeches…I think the leftists didn’t have any idea what they were dealing with and were exploiting it and were condescending… and that’s not the way that you go in and forge alliances – to condescend. But, on the other hand, were they worth condescending to? Yeah”.

Lee & Shlain: “The apolitical tone of the event was disconcerting to the New Left activists, who had once looked upon their hipster brethren as spiritual allies. The radicals disagreed with acid eaters who…believed that massive change would only come about when enough people expanded their consciousness [and who] rejected the possibility of revamping the social order through political activity, opting instead for a lifestyle that celebrated political disengagement”.

It was uneasy and unstable, this coalition, Counterculture, with its religious and political wings, between which ideology slipped like spilt mercury, restless and elusive. For the hippies, the ideological reference point was a form of Ur-libertarianism (with a mystic dimension represented by figures like Allen Ginsberg) - both freedom from and freedom to, and, as I mentioned earlier, delimited by a great absence; though not at all nihilistic, these were certainly a type of politics of negation.

As with the Pranksters and the Hells Angels, the hippies’ sense of liberty was freedom from absolute ethical injunctions other than in the most basic sense, freedom from ought (and, as an illustration of just how transgression can metastasize within such a sparse libertarian doctrine, it is worth mentioning that Allen Ginsberg went on to become a member of NAMBLA, the North American Man/Boy Love Association - a paedophile network).

“Consciousness”, in this sense, is not simply a repudiation of the State, it’s an anarchic rejection of any state, a belief in the transformative powers of the liberated human spirit to render the functions of the state, including even at the most basic level of security, redundant.

Dennis McNally tells me of the Be-In: “It was a marvellous day, it was a perfect day. The entire security for the event was two police on horseback, doing nothing. My favourite story from that day is a lady who went up to the police and said ‘I’ve lost my daughter, you have to help me find her’, and the cop says ‘lady, I can’t go down in there, they’re all smoking pot’”.

Dennis, a man of a sharp combative intellect which I am immediately conscious of in his presence, tells me this story as an example, I think, of how the benign generosity of the hippies managed to disarm the disciplinarian impulses of the reactionary state - proof of the capacity of passive resistance to dissolve the Cultural Hegemony, such that authority loses interest in deploying its coercive power, or enforcing things like drug prohibition, and simply observes, ineffectually, the hippies’ refusal to participate in the system.

But she’s lost her young daughter, I can’t help but think, and must be panicking, and requires a level of help that is probably above the competence of semi-naked gyrating acid freaks who don’t want their trip spoiled by maternal terror.

Of course, politics is the irrefutable principle of human societies. This fact, I’m certain, has been true since man pulled himself from the swamp but, at the very least, it has held for the two and a half thousand years since the Greeks took a stab at communicating it to everyone else. This fact, despite the hippies’ best efforts to dispel it with the force of “consciousness”, became ever louder and more insistent in the Haight, until it was eventually left with no other option than to march in and restore the natural order.

The first best example of this came in the form of Bill Graham or, at the moment of his birth, Wolfgang Grajonca, a German Jew who began his journey across wartime Europe and over to the United States as an eight-year-old, while his mother remained to perish in the death-gears at Auschwitz.

Graham arrived in San Francisco via a tough upbringing in the Bronx and tougher military tour in Korea before making contact with the San Francisco MIME Troupe, a radical theatre group whose members performed free acts of political theatre in public places, repeatedly defied the prohibitions of authority, and sought to change America through the same form of exemplary cultural movement as the hippies.

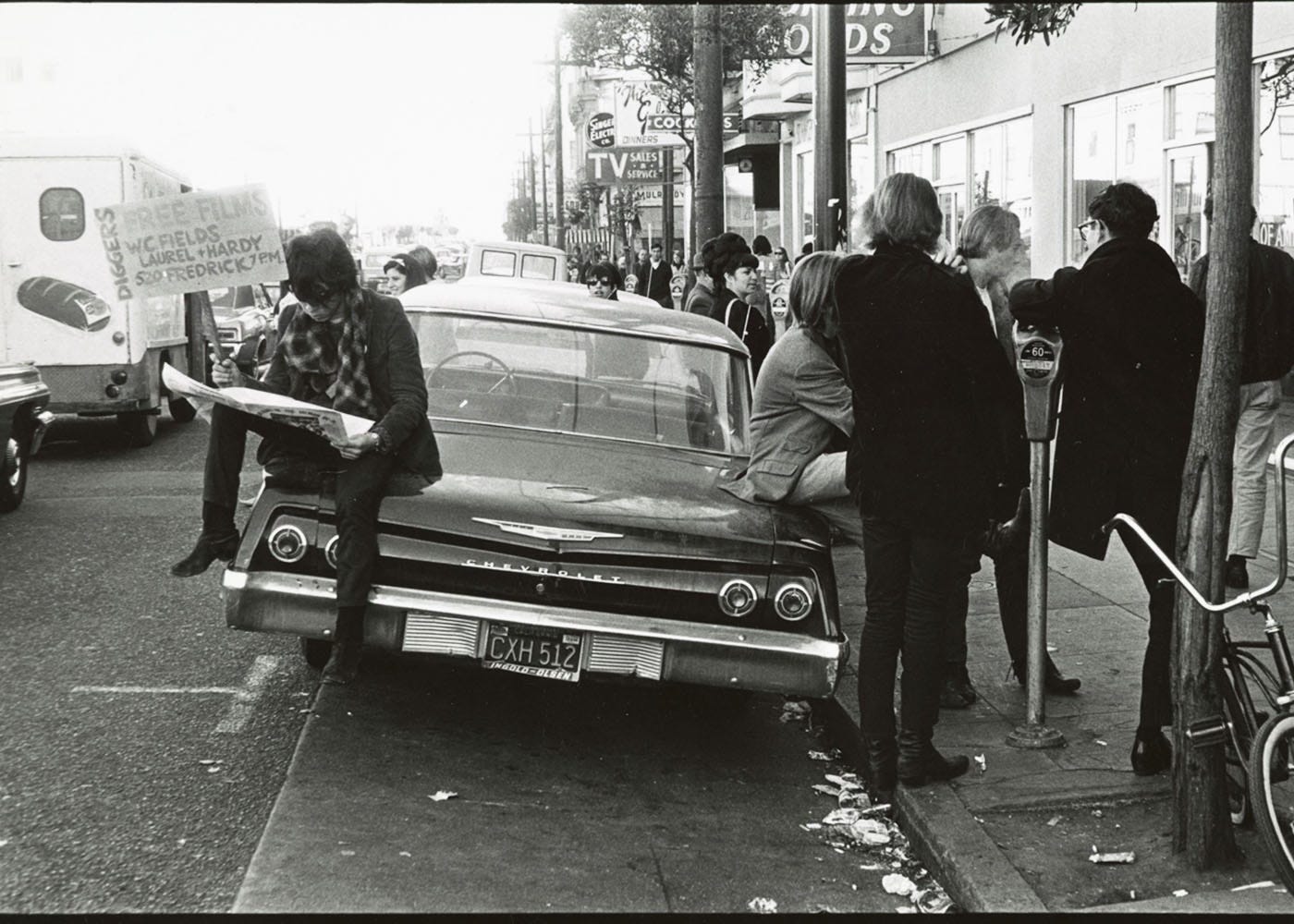

From the MIME Troupe came the Diggers, an anarchist collective that perhaps best embodied the Haight’s hybrid politics of communal-individualism, in which the interests of community are promoted through Libertarian individualism, anti-materialism and anti-statism, and which tried to develop from theatre a form of praxis that would challenge the apparatus of economic exploitation. In an early manifesto they proclaimed “the US standard of living is a bourgeois baby blanket for executives who scream in their sleep…our fight is with those who would kill us through dumb work, insane wars, dull money morality… Any important human occupation can be done free… Give up jobs. Be with people. Defend against property”.

Dennis McNally: “The Diggers [were] radical Left-Wing theatre veterans of the MIME Troupe who had dropped out and decided to carry street theatre to its ultimate context and that was ‘the one thing they can’t exploit is free. If you give it away they can’t do anything with it’ and they started giving out free food to hungry hippies and they started doing these little theatrical bits like creating what they called ‘the free frame of reference’, just a big frame, and you stepped into it and they said ‘now you’re a work of art, if you put a frame around it, it’s a work of art’”.

Graham, however, took an alternative set of lessons from his experiences in the MIME Troupe. A natural organiser with a wide smile, loud charisma, explosive temper and combative sense of justice (“one thing that growing up in the Bronx taught me: I got my rights”), Graham arranged finance for the legal defence of beleaguered Troupe members periodically dragged away on obscenity charges, by staging benefit concerts in the Bay Area. It was in these fundraisers that he spotted a business opportunity and unlike his former colleagues, he wasn’t interested in the philosophy of “free”.

In the mid-‘60s live music was still presented in the antiquated, torpid format of seated spectator events; there was nowhere in which the blaring rock bands of the counterculture could jam before an audience that wanted to drop acid and dance. Together with a rival promoter, Chet Helms, Bill Graham established San Francisco’s “ballroom scene”, live music promotions staged at Graham’s Fillmore Auditorium and Helms’s Avalon Ballroom which featured combined bills of bands like The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Quicksilver Messenger Service together with psychedelic light shows and expansive dancefloors. Given how critical the music scene was to the economy of the Haight, these enterprises quickly became indispensable, and their proprietors hugely influential.

In Graham, the Haight-Ashbury counterculturalists had among them someone who broadly shared their left-leaning, progressive outlook and was invested in the community, but who took a traditional, materialistic approach to business and the organising principles of local economics, in contrast to both the hippies and politically conscious radical groups like the Diggers.

When generators and flat-bed trucks were needed for free shows in Golden Gate Park, it was Graham who supplied them; when finance was required for legal defence work and community assistance projects, it was Graham who coughed up the lion’s share; when it was necessary to engage San Francisco’s civic institutions and negotiate the bureaucracy, it was Graham who would often assume a leading role. For all the utopian talk about expanded consciousness and new modes of living, so much of the Haight’s ability to function as an alternative community depended on the unsentimental pragmatism of people like Bill Graham, which eventually overwhelmed the dreamy idealism of Chet Helms and devoured most of his operation, to leave Graham as San Francisco’s pre-eminent impresario.

David Gans: “Bill Graham being as ambitious as he was, it was bound to take off and be more commercially successful because Chet Helms, who ran the Avalon, was a much more laid-back hippie, Bill was never a hippie”.

Dennis McNally: “Bill Graham who was all about work ethic, being organised, being on time and delivering very high quality – now it sounds like your basic hippie would want to work with Chet and not Bill, but one of the side-effects of Chet’s hippieness was there would be times when he didn’t have money to pay you, Bill always had money to pay you, so for working musicians after a while it became a pretty easy choice”.

Bill Graham, and his relationship with the hippies, is an example of where the Haight encountered what we might call the “Starbucks Paradox”, a facetious objection beloved of the Right (and sometimes idiotically endorsed by sections of the Left) which had its glory years during the anti-globalisation demos of the early millennium and into the post-crash “Occupy” era. The Starbucks Paradox holds that it is impossible to advance a critique of Capitalism if you have recently purchased a coffee from Starbucks, or bought something from Amazon, or, latterly, owned an iPhone/Macbook. This was the objection levelled at Graham – that in running a successful business, he was guilty of advancing Capitalism, and exploiting the community in the Haight.

What the Starbucks Paradox ignores, or pretends to ignore, is that when both the global economy and the nation state are arranged according to the rules of Capitalism, then it is not possible to exist outside of Capitalism. That does not make Capitalism the immutable law of the universe and its metaphysics, as the Right likes to suggest, nor preclude it from critique. In fact, all that this facile argument achieves is to buttress the fallacious moral apology for Capitalism, which is to suggest that the Capitalist system is subject to ultimate democratic accountability via the mechanism of individuals exercising choice within the marketplace. This is why the Right loves the Starbucks Paradox, it’s an attempt to bait anyone credulous enough on the Left into accepting the premise of Capitalism, and it’s why anyone on the Left seriously advocating consumer behaviour as a means to fatally undermine Capitalism needs to give themselves a slap.

Tom Hayden and Students For A Democratic Society at least in part understood that the prevailing systems of power had to be challenged on a national level, which would require an enormous effort of political organisation and an attempt to work through the existing institutions. Bill Graham understood that for the community and its enterprises to be self-sustaining it meant working within the existing systems, and that some level of professionalism would be required. Many of the counterculturalists in the Haight, however, fell victim to the assumptions of the Starbucks Paradox, and the siren calls of Ken Kesey, that it was possible to live outside of Capitalism, that some alternative system could exist within the system, that Bill Graham and those like him were simply hypocritical liberals playing the capitalist game.

The “state without the state” is the project that The Diggers embarked on, out of conviction that it might be possible to organise around Kesey’s principle, to give it form. Lee & Shlain:

“The Diggers went about their business as if Utopia were already a social fact and everyone were free. They chided other lefties for being stodgy, dull and fixated on social models that had little relevance to the situation in the United States….tough, charismatic and streetwise, the Diggers illuminated the Haight with wild strokes of artistic genius. In acting out their version of an alternative society, they emerged as the avant-garde of American anarchism…They were more activist-oriented than revelatory; things were real when people did them, and what they did had to relate to the basics: food, clothing, shelter, creativity. As a counterpoint to the vague love ethic of the flower children, they promoted the no-nonsense ethic of ‘FREE’!”

The Diggers organised “Free Stores”, ramshackle charity shops in which all the donated goods were free. They ran a soup kitchen in Golden Gate Park, where mal-nourished hippies queued to step through the “free frame of reference” and receive a bowl of meat and vegetables. They organised healthcare clinics staffed by medical students and crash pads where the homeless could find shelter; but it is hard to see how their programme differed from traditional, basic charity, of the type practiced by groups like the Salvation Army.

Beyond the revolutionary street theatre (and you might say that the church also goes in for theatre, in a big way), their efforts were directed at rescuing people from tumbling into oblivion: starvation, exposure, disease. But surely rescue from oblivion cannot be the highest ambition of a new American Utopia? Soup kitchens and shelters are a wilderness wandered by those who have dropped through the bottom of society, they are not the basis of a new, thriving, egalitarian community. The Diggers’ errant sibling, Bill Graham, built an alternative system in which people could earn, could feed, house and clothe themselves, but it was not “free”, and it meant departing from the ideological purity of Digger anarchism and Kesey’s politics of renunciation; this is where the community in the Haight, dizzy on acid, love and utopian dreams, had to confront the insistent concepts of politics and political choices.

David Gans: “[Bill Graham] took a lot of shit from the hippies about being a profiteer, but everyone was headed in that direction. It’s not possible to live in a ‘cashless society’, y’know? The Diggers found that out, and the MIME Troupe found that out, and all the hippies found that out and the Jefferson Airplane found that out when they became phenomenally wealthy rock stars”.

And this great “finding out”, the inevitable collision with reality, arrived in the Haight during an horrific series of months in 1967 that became known as the “Summer of Love”.

Next — Lessons From The Counterculture Part 6: The Horrific Summer of Love

Reading:

Martin A. Lee & Bruce Shlain - Acid Dreams

Dennis McNally - A Long, Strange Trip