Lessons From The Counterculture Part 7/9: The Defeat

1968, the Left goes to war

Note: this series is intended to be read in sequence, and this part makes references to personalties and concepts developed in the preceding parts.

“As 1968 began, I felt I was lying on the knife edge of history…Like a Greek drama, it started with legendary events, then raised hopes, only to end by immersing innocence in tragedy – an experience, for those who went through it all, felt to this day in failed dreams, enduring hurts, unmet yearnings” – Tom Hayden, Rebel.

1968

The youth are running. Protests, sit-ins, riots, confrontations, police violence, the future’s coming, American university campuses explode in rage and defiance. At Columbia University a week-long student occupation is broken-up by a column of police that surges through the choking clouds of tear gas and into the buildings, clubs colliding with cartilage, students defending themselves with fists and sticks. Students in Paris and Berlin rise-up in solidarity with Columbia, across the world the youth sprint into battle against state repression, against the war, against the past. Victory in America as Lyndon Johnson announces that he will not seek re-election. There will be more protests, marches, demands, battles and blood. Then come the assassinations. And Chicago. And Nixon. And defeat.

The violent confrontation between “The Movement” and the state came at a moment when the various branches of the Counterculture had coalesced into a muscular bloc that was bent on forcing a radical change to the status quo in America. The Civil Rights movement, the Anti-War movement, the Black Power movement (including the Black Panthers), the New Left, the Yippies all came together in a grand alliance, and declared war. This was FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s blackest nightmare, the point at which the sirens started blaring on The Hill and the political establishment began running for the bunkers.

One of the consequences of the spectacular arrival of the Hippie movement in 1967 was that the radical Left immediately apprehended its insurgent cultural power, ability to beguile and excite mass media, to inspire and recruit youth throughout America. And the Left took notes.

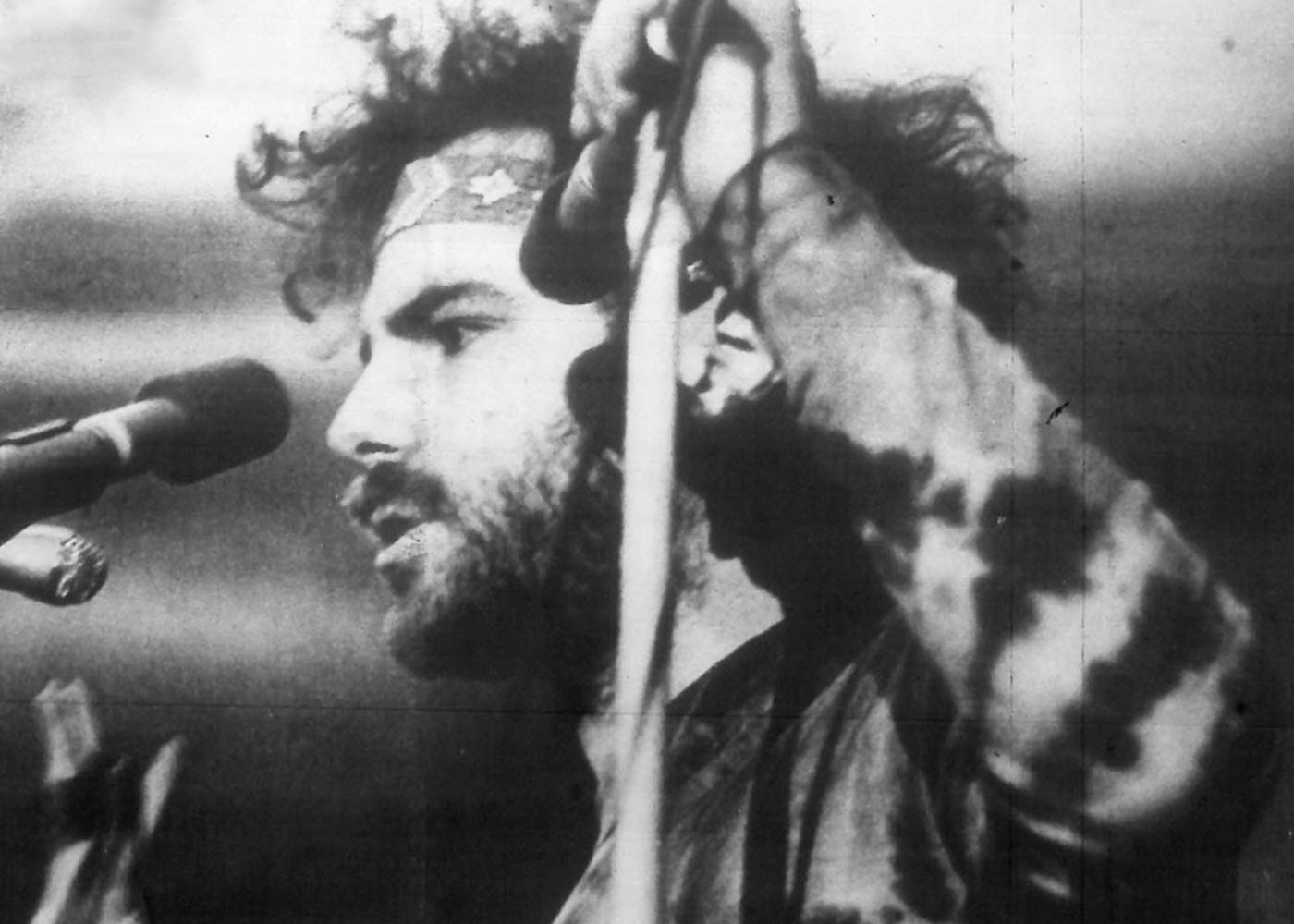

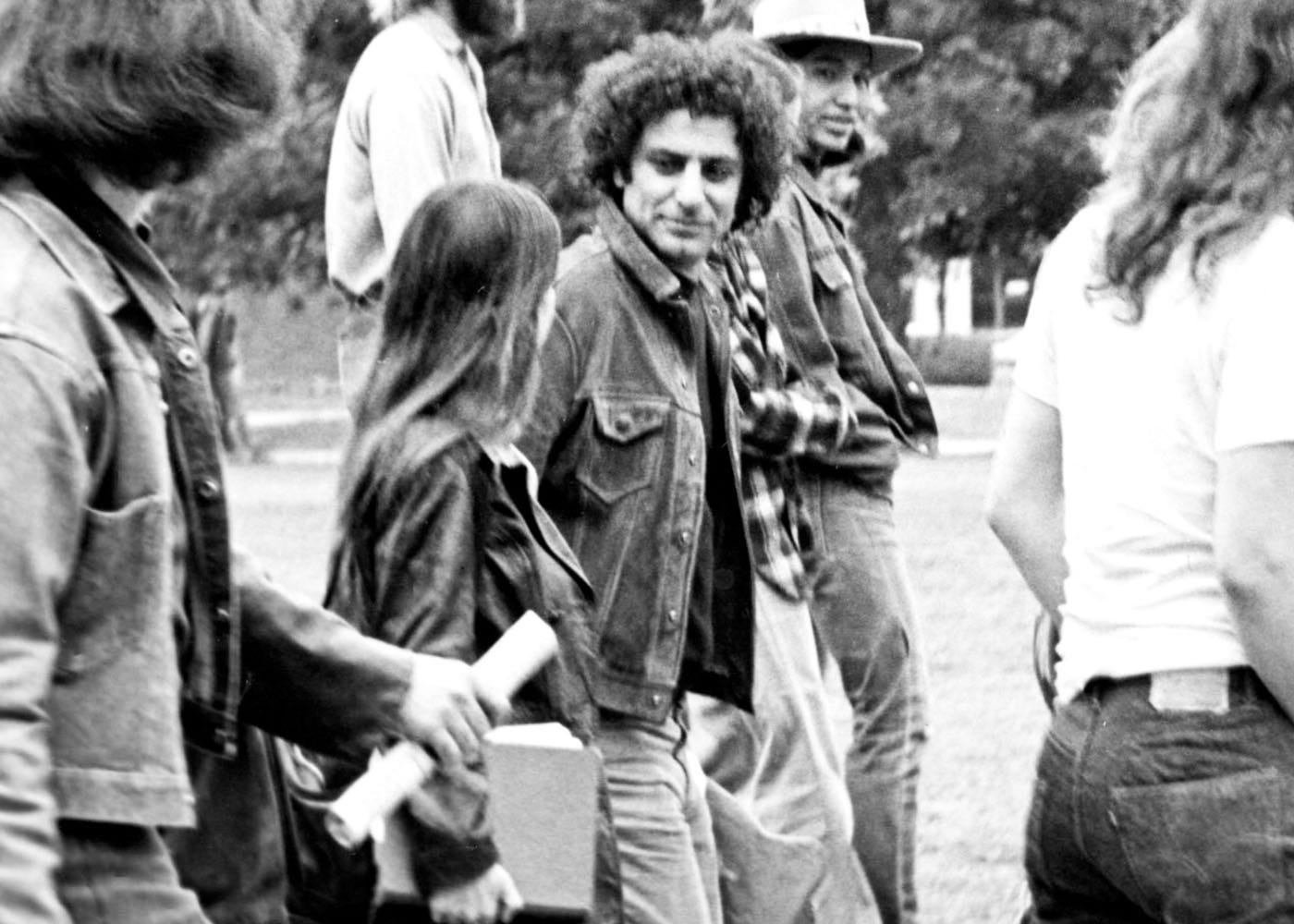

The hippie freak show had fascinated square society in a way that the New Left and Civil Rights movement never could. With the latter, middle America was either cautiously supportive or outwardly hostile; with the hippies, it was incredulous, and often titillated. This energy, pulsing through the cultural ley-lines, was intuitively felt by Jerry Rubin, one of the leading lights of the New Left at Berkeley and future indictee in the trial of the Chicago Seven.

Jerry Rubin had been hurled at life’s sharp edge in his early twenties, when both his parents died within a few months of one another and he was left as sole carer for his thirteen-year-old brother, Gil. The pair moved to Israel, where they joined a Kibbutz, Jerry studied sociology and encountered living, breathing communists for the first time. In ‘64 he returned to enrol at Berkeley, after six weeks he dropped out and devoted himself full-time to radical student politics, beginning with an illegal trip to Havana.

Jerry Rubin in Growing (Up) at 37:

“I looked at the Cuban people and envied their revolutionary spirit, their enthusiasm and aliveness. I wanted to stay and live there. The Cubans said, ‘No, your struggle is in America’. We interviewed Che Guevara…he blew my mind when he told us that if he had choice, he would return to North America with us. ‘The most exciting struggle in the world is going on in North America. You live’, Che Said, ‘in the belly of the beast’. Inspired by Che, I returned to the United States. At the border the U.S. government revoked my passport.”

Rubin’s return to Berkeley coincided with the heat and light of the Free Speech Movement and anti-war protests, in which he became a leading figure, founding the “Vietnam Day Committee” in 1965 and organizing a series of demos and marches across America.

In contrast to the thoughtful, earnest Tom Hayden, Rubin was a firebrand revolutionary and controversialist. He was diminutive and scrappy, five feet five inches tall with dark, piercing eyes beneath a clenched brow, wild black hair and prolific beard, a balled fist of rage and energy. He had a salesman’s instinct for the power of spectacle, he was attuned to the rhythms of the mass media age, and understood its currencies: image, symbolism, notoriety; each more valuable than a thousand manifestos. He was an unconscious disciple of Gramsci, a sire to Steve Bannon, he set out to dazzle and inflame America.

Jerry Rubin, Growing (Up) at 37:

“I was a single-minded, one-dimensional fanatic dedicated to figuring out actions that would make life unbearable for the President of the United States…I was subpoenaed as a witness to a hearing of the House Committee on Un-American Activities…I wanted to do something to before the Committee that would grab the anti-war attention of the entire country. I decided to wear the uniform of an American Revolutionary soldier to the hearings…The press ate it up: it was on page one across the country. With that one zap I inspired rebellious people everywhere to be outrageous. I had used the media to spread my message”.

The appearance of the Hippies amazed Jerry Rubin. As their youthful carnival sang and danced its way through San Francisco, the monochrome pages of speeches, marches, debates, theory and fraught, conceptual shouting matches with the stiff suits, wrinkled faces and old aftershave in universities and meeting halls were suddenly splashed with colour.

But he was also conscious of the suspicion that lurked between his political wing of the Counterculture and this insurgent religious sect, antipathy that could prevent the Counterculture from realising its full revolutionary potential.

Jerry Rubin, Growing (Up) at 37:

“Berkeley radicals saw [hippies] as a diversion from politics; Hippies saw radicals as uptight politicians. I saw the hippies as a true political expression of the breakdown of affluent society. But I also thought radicals were right in focusing their attention on power and foreign policy. I therefore vowed to work to fuse the two forces”.

Rubin had a counterpart on the East Coast: Abbie Hoffman, a high-minded student of contemporary Marxist thought who had spent time with the Diggers in Haight-Ashbury and concluded that undermining cultural hegemony through spectacle, media attention and complete rejection of the system was more important than organising to assume control of political structures and the institutions; Rubin and Hoffman became close confederates.

Like Rubin, Hoffman had a gift for theatrics and self-promotion, during the Summer of Love in ‘67, he masterminded an invasion of the New York stock exchange, causing uproar on the trading floor by scattering bank notes from the public gallery as brokers swarmed and grasped at the cash fluttering down from above. It was a stunning demonstration of the vulgarity and indignity of American Capitalism. “Police grabbed the ten of us, dragged us down the stairs, and deposited us on Wall Street at high noon in front of astonished businessmen and hungry TV cameras. That night the attack by hippies on the New York Stock Exchange was told around the world – international publicity!.. I fell in love with Abbie”, Jerry Rubin writes in Growing (Up) at 37.

Going into ’68 the Counterculture felt the wind at its back. In October ’67 the “National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam”, or “Mobe”, an umbrella body for the factions that comprised the anti-war movement, organised 75,000 people to descend on Washington D.C in the largest anti-war demonstration America had yet seen, a demonstration that bequeathed some of the most iconic images of the twenty-first century when protestors pushed flowers into the barrels of the rifles that were being pointed at them by military police.

During the demo Rubin, Hoffman and Allen Ginsberg led thousands of costumed, tripping hippies to surround The Pentagon and chant incantations in a pagan effort to “levitate” the five-pointed Satanic fortress “three hundred feet” into the air and exorcise the evil forces within. The international media swarmed around them, this was the ethos of the Merry Pranksters elevated to a national level and re-imagined as a political campaign.

In place of the privatised disengagement and drug-induced solipsism of the Acid Tests, Rubin and Hoffman carried the early Hippies’ attack on Cultural Hegemony to its extreme: baroque spectacle pitched at a national, or even international, audience. But what they also represented was the arrival of celebrity within the Counterculture, of political entrepreneurialism. There had always been celebrities attached to the Counterculture, but Allen Ginsberg was famous as a poet, Bob Dylan or Phil Ochs as musicians, Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman became famous purely for being “Counterculturalists”.

On New Year’s Eve 1967 Abbie Hoffman, together with his wife Anita, Jerry Rubin, the activist Nancy Kurshan and the Merry Prankster Paul Krassner met at Hoffman’s home in New York, got high, and founded the “Youth International Party” or “Yippies”. Their logo was a green cannabis leaf over a red star, to symbolise the synthesis of the religious and political sides of the Counterculture, but their 1968 “Yippie Manifesto” confirmed that it was Kesey’s religious project of altered consciousness, personality and disengagement that had subsumed the political side:

“America and the West suffer from a great spiritual crisis. And so the Yippies are a revolutionary religious movement. We do not advocate political solutions that you can vote for. You are never going to be able to vote for the revolution. Get that hope out of your mind. And you are not going to be able to buy the revolution in a supermarket, in the tradition of our consumer society...Revolution only comes through personal transformation: finding God and changing your life. Then millions of converts will create a massive social upheaval”.

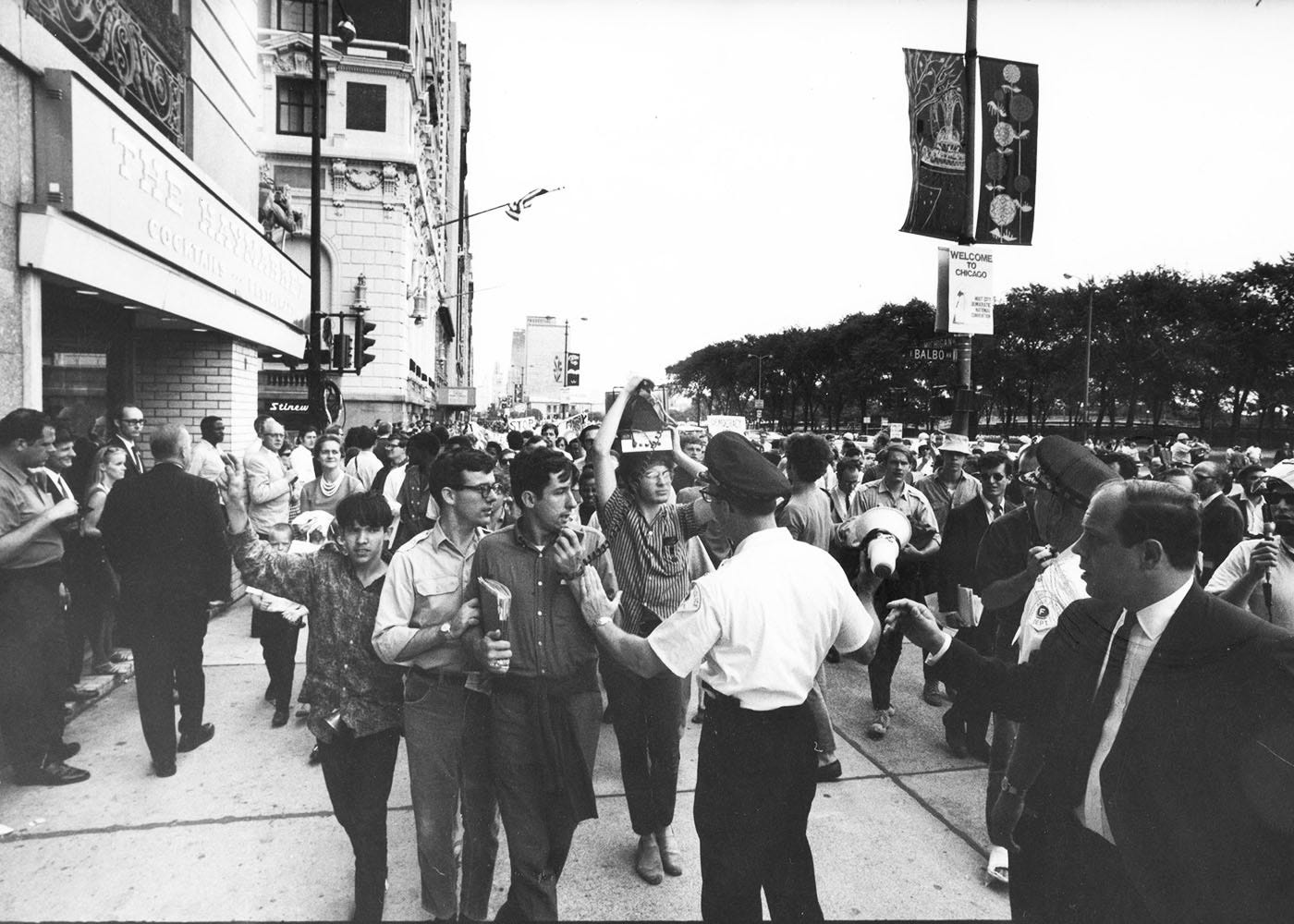

As the Counterculture surged towards Chicago the Yippies rode in as the political wing of the Hippie movement, their Dadaist performances and outrageous statements devoured by an eager media, filmed, photographed and broadcast as the manic face of American arsonists: a press conference to announce a “Festival of Life” in Chicago, a plan to contaminate the city’s water supply with LSD, shake up the squares, open minds. A late-night dust-up with police in Grand Central Station. A press conference a week before the Convention to inaugurate the candidacy of “Pigasus” for President - a small, stout pig arrested by the Chicago police along with several flailing Yippies, charges and trial to follow.

All this had the intended effect of proving to Conservative America that a generational ravine had torn its way through the nation and that the youth, the Left, encamped on the other side, were utterly unfathomable, conciliation impossible. The establishment accepted the Yippies’ warning that they were in a “spiritual”, rather than political, battle and responded with fear and violence – the beatings and tear gas at Columbia University, the riots, the clashes that burned across America.

Rock Scully, Manager, the Grateful Dead: “It was an incredibly disturbing time. We played in Detroit, and the whole downstairs had been burned-out by rioting and looting. The National Guard were in our streets marching down, y’know with rifles and helmets, down Haight Street and Market Street, it really felt very, very repressive”.

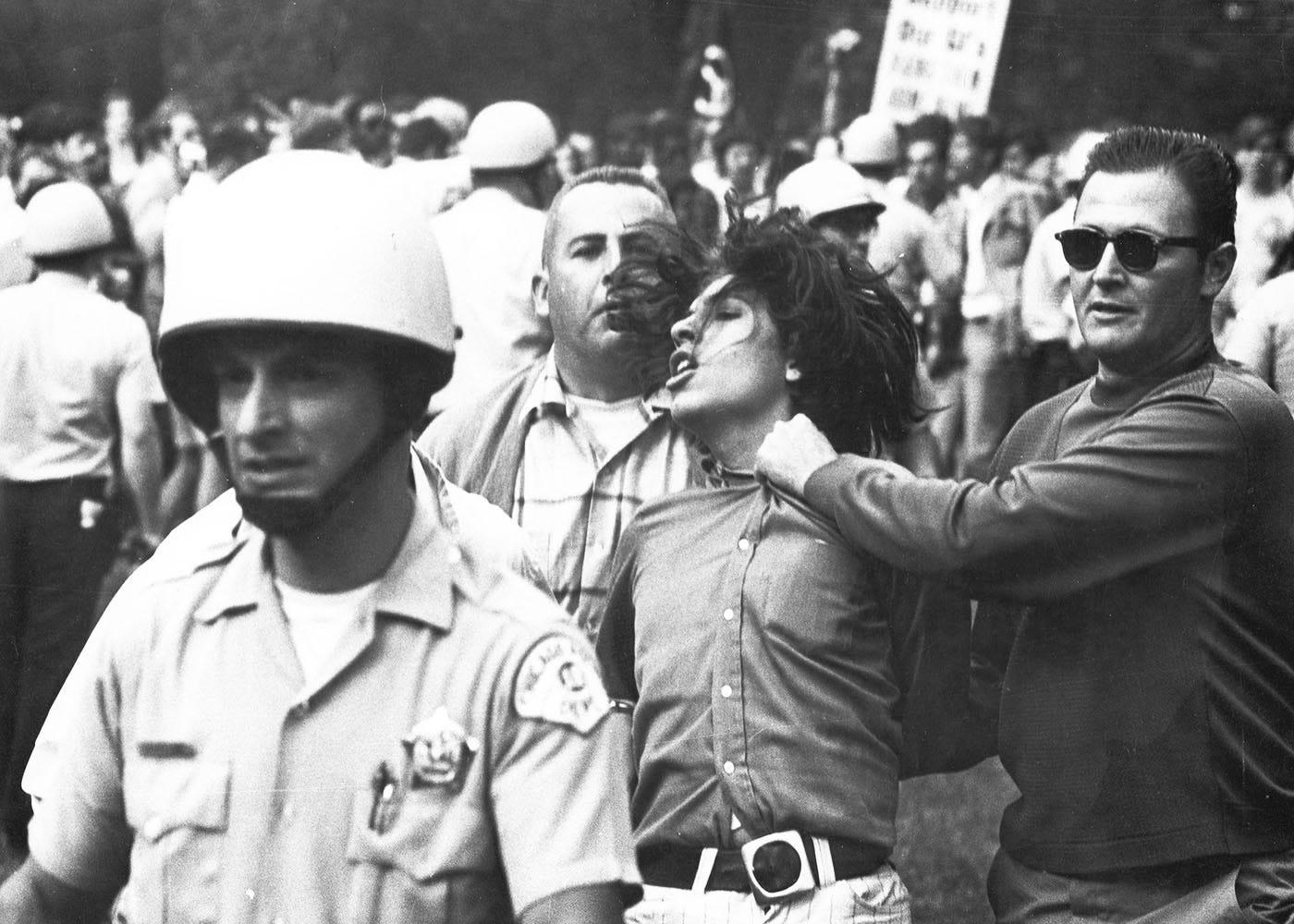

These pitched battles tumbled into Chicago in August, under the summit of a Presidential election, where a wide blue wall fell upon the Counterculture, submerging it in blood.

Rennie Davis of the Mobe on the violence at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, from his testimony at trial: “The police formation broke and began to run, and at that time I heard several of the men in the line yell, quite distinctly, ‘Kill Davis, Kill Davis’, and they were screaming that and the police moved in on top of me, and I was trapped…the first thing that occurred to me was a very powerful blow to the head that drove me face first down into the dirt, and then, as I attempted to crawl on my hands and knees, the policemen continued to yell ‘Kill Davis, Kill Davis’ and continued to strike me across the neck and ears and back…I must have been hit 30 or 40 times in the back and I crawled…I looked down and my tie was just solid blood”.

At the trial of the Chicago Seven, in which Rubin, Hoffman, Hayden, Davis and several others stood accused of inciting a riot in Chicago, the sutures between the religious and political wings of the Counterculture began to rupture. The Yippies wanted to litigate the charges in the media and turn the courtroom into a circus, Tom Hayden and some of the other New Left accused wanted to engage with the trial on its own terms.

Tom Hayden, Rebel:

“There were sharp differences. I was the most cautious of the defendants, wanting to reach the jury by pursuing a thorough, rational defence, combined with a public information campaign, stressing that a prolongation of ‘Nixon’s War’ would inevitably lead to widening political repression…The ‘Yippies’ were advocates of disruptive courtroom theatre, including deliberate contempt of court (as the judge defined it), because they thought that the media image would both desanctify the judicial system and win more identification to our cause”.

Though the Yippies had an explicitly political agenda, they belonged more to the Merry Pranksters’ ideology of disavowal and subversion than to the New Left’s project of a Socialist march through civil society and the institutions. In that sense, the Yippies were converts from the political wing, they had crossed the floor and formed a new bloc on the religious side, strengthening its meandering Libertarianism and politics of personality, and diminishing the Left’s attempts to fashion a broad-based movement capable of reforming the state.

There had always been distrust of the Yippies’ on the Left, in particular distrust of their emphasis on cultural insurgency. The Diggers had been roused to fury when Abbie Hoffman, whom they disdained as a shallow publicity seeker, concluded his time with them by publishing the details of all their various free-living schemes, “we explained everything to those guys [Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman]”, said Diggers co-founder Peter Coyote in a 1989 interview with Etan Ben-Ami, “and they violated everything we taught them. Abbie went back, and the first thing he did was publish a book, with his picture on it, that blew the hustle of every poor person on the Lower East Side”.

The Yippies’ form of Counterculture celebrity carried the Pranksters concept of “you are the show” to its ultimate incarnation, but in doing so risked collapsing under its own cultural weight. Unlike the Pranksters, the Yippies claimed to have a political goal, that their absurdism and theatrics were all part of some revolutionary teleology, in which the clown-face of the state itself would be unmasked, the system eventually rejected by its subjects as absurd. As Ken Kesey imagined in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, as Ken Babbs announced to me on that sweltering day in Oregon, “the institution will be institutionalised and the patients will be free!”

The urgent danger in this avant-garde, spectacular approach to political change is that it reduces everything, everything, to spectacle - the violence and assassinations, the repression, the Vietnam War, all merge into one great, psychotic spectacle, a vision of a disfigured, terrifying world. Does anyone trying to navigate their life within the prevailing system, as painlessly as can be hoped, really encounter the Yippies on television and begin to infer their third-order intentions to explode the Cultural Hegemony? Or do they just take this spectacle at face value? Tom Hayden tentatively approaches this question in his description of the Chicago trial in Rebel:

“Abbie and Jerry wanted to force the judge into revoking our bail the following morning…they wanted to end the trial with us already in jail…I felt that deliberately acting to have ourselves thrown in jail would only persuade people that we were intentionally trying to stop the trial through disruption and would throw a crucial degree of support back to the judge…The next morning, Abbie and Jerry appeared in court wearing black judge’s robes covering blue Chicago police department shirts. Even I had to applaud their sense of theater”.

My own feeling is that Hayden’s instincts were correct, the Yippies’ theatrics would not “desanctify the judicial process” within the public mind, but simply confirm the right-wing judgement that hippies, Leftists, were nothing more than contemptuous degenerates.

Abbie Hoffman’s testimony during the trial was a masterclass in narcissistic performance, in which he talked only of himself, an ungenerous reading of which might conclude that he felt his own thought so elevated as to be unreachable by the primitive urges of the squalid American mind. Rennie Davis of the Mobe, in contrast, offered a simple account of his opposition to the Vietnam War, intelligible to anyone, and carrying with it tremendous moral force.

In voluntarily occupying the role of stoners, freaks and clowns within media representation (and cultural consumption) of the Counterculture, the Yippies’ project directly reinforced, rather than undermined, the Cultural Hegemony. The Yippies didn’t subvert the ideological propaganda of the state, they supported it, enlisting to act as a lightning rod: dissent reduced to spectacle, politics to celebrity, revolution to satire, the status-quo preserved. This is precisely why television, acting on behalf of the establishment, was so keen to broadcast Cliff the Hell’s Angel in the mid-60s, and why it was Cliff, not Hunter Thompson, who was presented as the show’s protagonist.

Perhaps this paradox is not as self-defeating as it appears to be at first glance. Perhaps the Pranksters, the Hippies, and finally the Yippies, had a natural ideological affinity with the Liberal Capitalist state, and had been prepared to strike a bargain all along.

As for 1968? The future rolled back across the horizon like retreating clouds, its shadows tracing the last thin shapes of hope and deliverance across the arid plains of the Nixon era.

State repression of the Left had been largely successful, radical organisations were riven with government agents and informants, even Jerry Rubin’s personal bodyguards were Hoover’s plants. The surge of resistance that had brought down Lyndon Johnson and turned America against the Vietnam War met its nemesis in Chicago, where the young idealists who had worked to get Kennedy and McCarthy elected were battered senseless in Grant Park.

The war metastasised into a theatre of Grand Guignol, both soldiers and their victims conjoined in horror and madness, the jungles of Southeast Asia devoured by a vast tumbling fire, the soil steeped in poison, the waters awash with bodies and blood. The revolutionary fires that had raged across Europe had burned themselves out; in Brazil and Mexico they had been extinguished in massacres.

Tom Hayden, Rebel:

“I had reached exhaustion; so had the protest. So had the hopeful movement I had hoped to build only a few years before….Reform seemed bankrupt, revolution far away… Rarely, if ever in American history, has a generation begun with higher ideals and experienced greater trauma than those who lived fully the short time from 1960-68. Our world was going to be transformed for the good, we let ourselves believe not once but twice, only to learn that violence can slay not only individuals, but dreams. After 1968, living on as a ruptured and dislocated generation became our fate, having lost our best possibilities at an early age, wanting to hope but fearing the pain that seemed its consequence. As Jack Newfield wrote, after 1968, ‘The Stone was at the bottom of the hill and we were alone’”.

And as for the Left? It drew all the wrong conclusions, as defeated movements nearly always do.

Next — Lessons From The Counterculture Part 8: “The Personal is Political”

Reading:

Jerry Rubin, Growing (Up) at 37 [1976]

Tom Hayden, Rebel. A Personal History of the 1960s [2003]

Yippie Manifesto [1969]