Lessons From The Counterculture Part 6/9: The Horrific Summer of Love

The Hippie dream becomes a nightmare

Note: this series is intended to be read in sequence, and this part makes references to personalties and concepts developed in the preceding parts.

The counterculture is global, its political side marching, fists raised, bellowing through loud-hailers in New York, Paris, London and Berlin in columns of red and black. The religious side spread primary colours through the grey streets, rainbow-painted Volkswagen love buses, bright swirling patterns across shirts, dresses and long coats; flower garlands, painted faces.

Square society’s fascination with the hippies, first inspired by the spectacle of San Franciso’s “Be-In” Hippie festival, has been steadily escalating. Hippies are on the front of Time Magazine, hippies crowd around a bewildered Harry Reasoner, who presses on down Haight Street in a grey suit and tie, like a desperate refugee from the 1940s, trying to maintain his even patrician delivery while filing an on-camera report for CBS news, pounding drums and clanging metal swallowing his voice, the sidewalks teeming with youth.

The intensity of the press attention across the Spring of ’67 generates a cultural wave that gains irresistible momentum. Young people across America grow their hair and roll joints, Scott McKenzie’s maudlin pop ballad San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair) scales the charts in the US, UK and Europe. By the summer, the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, an independent Hippie republic, has become a meme, and now tens of thousands want to escape to the Liberated Zone.

Robert Christgau, Village Voice: “There was a lot of stuff in the press all the time. People saying ‘well, maybe this utopian idea will actually work’. Of course, it was complete nonsense and our initial scepticism was completely justified”.

Dennis McNally, PR, Grateful Dead: “Too many people came. They weren’t people in their 20s with some world experience and a little bit of money in their pocket and an ability to negotiate their way, they were high school kids saying ‘feed me, help me, I want to be a hippie’”.

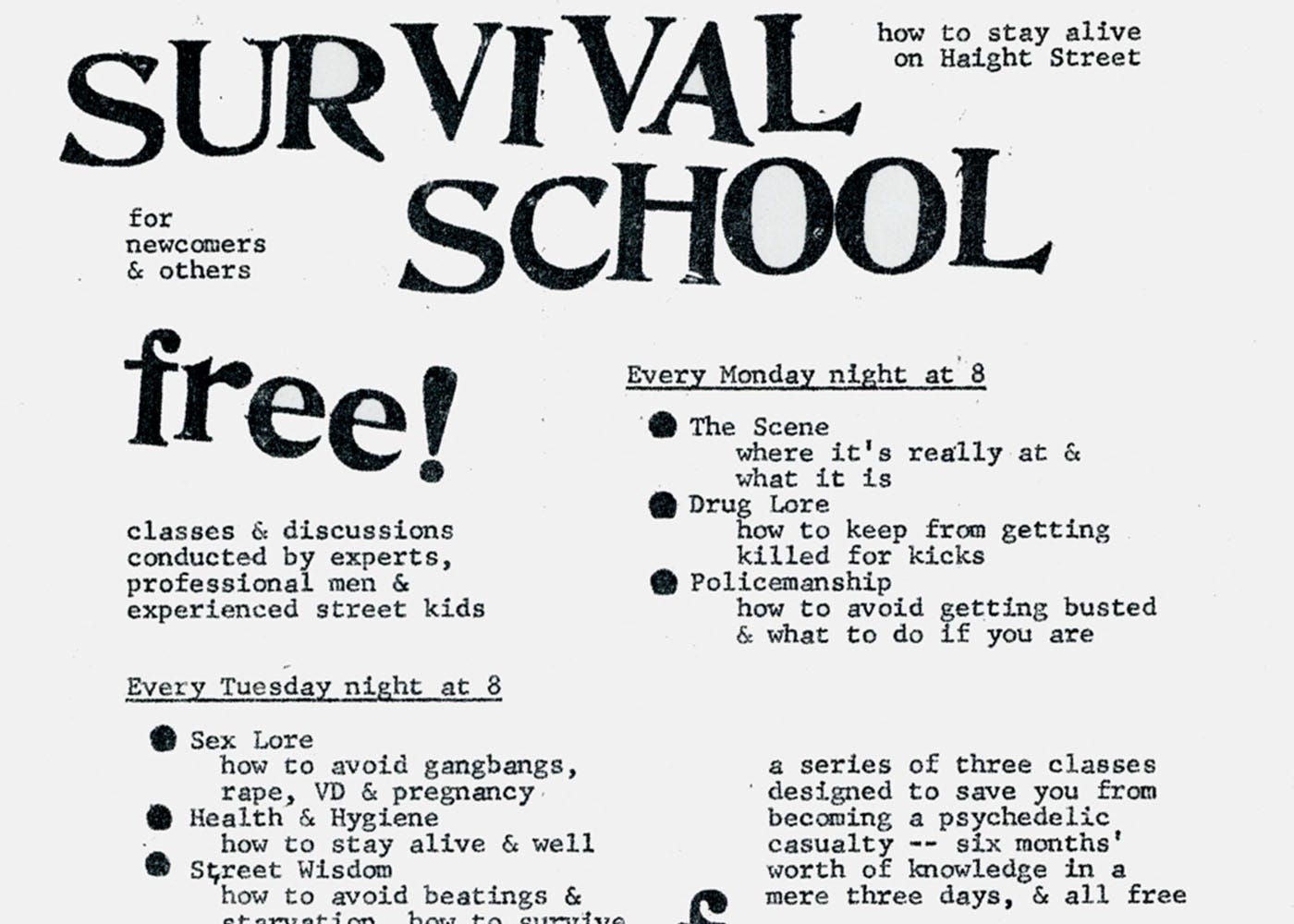

Looking back through the film archives of the Summer of Love is a shocking experience. Yes there’s a lot of dancing, kissing, smoking pot, inspiriting reels of light and colour; but there are also unsettling blemishes across the footage, like tumour shadows, the occasional shot that must have been framed deliberately by a nervous cameraman who has been hired to capture utopia, but wants to dispatch a silent warning to the outside, to history: a grubby teenage girl with wide, staring eyes wanders across a patch of grass, head jerking from left to right, occasionally turning, clearly in an elevated state of psychological distress; a wall of flyers across which the camera slowly pans, they advertise seminars on “How to stay alive on Haight Street”, “How to avoid gangbangs, rape, VD & pregnancy” and “How to avoid beatings and starvation”.

Rock Scully, Manager, Grateful Dead: “I’d go down and look at that wall in the police station of runaways whose parents were looking for them. It was just frightening”.

Mike Wilhelm, musician, The Charlatans: “They just got exploited. Drug dealers, organised crime started moving in”.

Peter Albin, musician, Big Brother & The Holding Company: “It was joints, y’know, and some hash in ’66. In ’67 it was points, it was smack, y’know, ‘you want some meth?’. The scene was changing and becoming a place you didn’t want to be. My wife was held up at knifepoint and I said ‘that’s it, we’re leaving’”.

And here once more we find those left in the cold, victims of someone else’s purpose. Freedom, undefined, amorphous freedom, became freedom to exploit, freedom to pimp, freedom to take and take until all the colour and love and good intentions were denuded and “utopia” was revealed as sobbing, damaged, regretful poverty.

This is the paradox of the Hippies’ strain of Libertarianism. As with the individualism-communitarianism of the Pranksters, they wanted a community that was selective and self-selecting, a community-without-society, without having to confront The Man, or organise the poor, or deal with all the decades of grievance and inheritance and ideology or look up at the vast inscrutable wall of history and try to describe what exactly might be beyond it, and how one could possibly begin to scale it.

It’s easy to see how this ethos could attract so many people, there is no definition, which means it’s entirely open to projection, it is whatever you want it to be, you can be anything you want to be. But, naturally, the pursuit of one’s own desires will collide those of others and there will be rights conflicts, that is why the mediating forces of politics and the state exist.

When Lee & Shlain describe the experiment in Haight-Ashbury as “a revolution that would…destroy the political bonds that shackle and diminish us” and that “Human liberation was something to be acted-out”, well, political bonds are the abiding principle of human societies, and if you give everyone a stage on which to “act-out” as they choose, you may find that you don’t enjoy the performance quite as much as you had hoped to.

Again, here we arrive at the active zone of ideology, at the indispensable requirement to properly identify the ideologies at work. In 1978 the British writer and counterculturalist Barry Miles interviewed the Canadian rock group “Rush” for an article in the NME. The interview soon became adversarial, Rush, and in particular their drummer and lyricist Neil Peart, liked to evangelise for Libertarianism. They stuffed their work with references to the ideas of Ayn Rand, their 1976 album 2112 is an absurd, baroque panegyric to Rand’s book Anthem, in which the protagonist struggles to express his individuality, and creativity, from under the anonymising repressions of the State.

During the interview Peart advocates passionately for individual freedom, limited government, and the dissolution of political bonds; the purist’s vision of American freedom, in which man sets forth across the abundant, empty plains towards the horizon of his heart. As a sharp Leftist from the European tradition, Miles could see that this was all bullshit – he entitled his article Is everybody feelin’ all RIGHT (Geddit…?).

What Miles sought to highlight in his article is that this form of shallow Libertarianism is not new, and that its long history belongs to Right-wing political ideology. The concept of the abbreviated state, of human potential uncircumscribed by the demands of others, of basic needs being provided either by charities or by some magnanimous tycoon or corporation – we have seen all this during former epochs, it led to exploitation, injustice, poverty, its only advocates the small class of people that were able to get rich off it. “Make sure that next time you see them, you are there with your eyes open and know what you see” Miles concludes of Rush and their ideas, “I, for one, don’t like it”.

And in 1967 the Diggers didn’t like what they saw on Haight Street. They issued Uncle Tim’$ Children, a pamphlet that excoriated the hippies, and in particular Timothy Leary, for their recklessness, cynicism and selfishness:

“Pretty little 16-year-old middle class chick comes to the Haight to see what it’s all about & gets picked up by a 17-year-old street dealer who spends all day shooting her full of speed again & again, then feeds her 3000 mikes and raffles off her temporarily unemployed body for the biggest Haight Street gang bang since the night before last. The politics & ethics of ecstasy. Rape is as common as bullshit on Haight Street…. The selectively expanded consciousness does not notice misery. Misery is not beautiful”.

To their credit, the Diggers, together with a coalition of alarmed Haight-Ashbury old hands tried to do something about it.

Peter Albin: “There were community meetings at churches and community halls. They were afraid that there was going to be a problem with housing, food, hygiene. I think they came up with good solutions, there were different houses where these people could go and get food. The Diggers started providing free food in the park.”

This urgent organisational effort pitched the anarcho-libertarians of the Haight straight into the first principles of the political state: the need to band together to confront common problems, the need to deter transgression, the need to form institutions, even the requirement to raise revenues.

Rock Scully: “1% it was called. We charged 1%. The Grateful Dead paid 1%, Bill Graham paid 1% out of all the profits just to feed these people and find them housing and cover their legal expenses and so on. We did a benefit and started HALO, the Haight Ashbury Legal Organisation, started The Free Clinic because people were getting sick, and living outdoors and getting bronchitis…”

Once you establish a new society you soon find that you have to run it. The Diggers efforts to denounce and confront the depredations of the Summer of Love were laudable, but they saw all the pain and squalor as a consequence of greed and economic exploitation, rather than in train with the political logic of the Haight. If you disable, rather than reform or re-orientate, the functions of the state, as both they and the hippies advocated, misery is precisely what can follow.

The coercive functions of the state as functions are politically neutral, they can be directed to repress or to liberate, to protect or to persecute; that’s the political challenge; they are not sufficient but they are necessary, and in their absence violence and exploitation will approach.. “Consciousness”, and good intentions, are inadequate substitutes. Contemporary campaigns to abolish the police would do well to study the files on this subject.

Rock Scully: “The city fathers were getting concerned…to make people aware that they were cracking down they busted us [the Grateful Dead]….it just really told us that it was going to become an adversarial kinda situation. And it was”.

To illustrate this point about the need to address messy material realities, rather than rely on nebulous concepts of “consciousness” and good intentions, I’ll make a brief digression into an example from the most extreme form of social breakdown.

Some years ago I made a series of films about the civil war in Sierra Leone, a gratuitously distressing conflict in which the state collapsed and the country was overrun by hordes of blood-soaked psychopaths that elevated rape and death-by-torture to industries of mass production. They maimed, killed and abused children, amputated the hands of entire communities and roamed the streets of Freetown in snarling, wild-eyed packs looking for opportunities to commit casual murder.

In the final episodes of the series we focused on post-conflict Sierra Leone, the efforts to rehabilitate the child soldiers, describe a meaningful future to the rape victims and resurrect a functioning democracy. Joe, an academic attached to the project, was there to advise on themes of post-conflict reconstruction and the role of international agencies.

Joe was a slightly stooped, thin veteran of the 60s Counterculture and Vietnam War protests. He had a loud American accent, wavy grey hair and an Old Testament beard. He still wore leather sandals. He was jovial and perspicacious, he had started trying to change the world for the better forty years beforehand, and had never stopped.

At the time the buzzword in international development and post-conflict reconstruction was “peacebuilding”, in all our interviews representatives of the major NGOs and international agencies would talk loftily about finding opportunities for “peacebuilding” and helping victims emerge from the trauma of war. Every time they did so Joe would curse and lift his sandals up off the floor, “gah!”. After a few days I asked him why he was so triggered by the utterance of this particular term.

Joe explained to me that over 40% of countries that emerge from civil war return to civil war within ten years. This concept of “peacebuilding” was, in his judgement, utterly fatuous, concerned as it was with “getting people to be nice to each other”. It had nothing, he explained, to say about why the war started in the first place, the material conditions, the reality of people’s lives that provided a context in which a formally dutiful citizen would be prepared to go out and murder his neighbour, and induce a thirteen-year-old child to do the same. It was, in other words, hippie bullshit, and that is why so many of these societies quickly slide back into chaos.

So much for the religious side.

The attempt to create a “state without the state” in Haight-Ashbury, to live without materialism, the project to drop out, that had originated with the Beats and the Pranksters, the shallow impulse to say “Fuck It”, as Kesey advocated, none of this had proved to be an adequate response to the problems and injustices of American society.

The concept of breaking the cultural hegemony through privatised, personal change was spectacularly unsuccessful, the consequences appalled most of the American public and brought the wrath of The Man down on San Francisco – and with justification, too. A new democracy based on justice and the common interest could never be based on the politics of narcissism and self-interest that typified the hippies' attitude towards the social organism.

When I put this point to some of the more thoughtful hippies, they often took it badly. “It is possible to be true to yourself and also to care about others, your community and building a better world” would be the typical reply. But on which of those propositions is your political outlook premised? What happens when they conflict? In studying the lessons from Haight-Ashbury we find no better answer to these questions than that served by LuAnne Cassady, right at the start: “Neal will leave you in the cold anytime it's in his interest”.

Back in New York, getting ready to fly out to San Francisco, I ask Anthony DeCurtis of Rolling Stone about ’68, the defeats, the downturns, what had happened to the optimism and naivety that had attended the Be-In. “You had the radicalisation of the Counterculture”, Anthony says, “what had been ‘consciousness will change this culture, consciousness will change our society’, if you take LSD and you listen to the right bands and you believe the right things everything will change, it will just happen - I don’t think anybody believed that anymore. It was a transition from a politics of consciousness to a politics of the street, a straight-up politics of revolution”.

Next - Lessons From The Counterculture Part 7: The Defeat

Reading:

Martin A. Lee & Bruce Shlain - Acid Dreams

Dennis McNally - A Long, Strange Trip

Diggers - Uncle Tim’$ Children