How Prince Changed the Music Business

And what independent creatives can learn from it.

Introduction

At the present moment there is blood all over the floor, viscous and stinking, and more of it daily washes in.

2024 has been a desolate year for the creative industries, another interval in its age of unreason, where the economic and creative logic of independent film and television has collapsed and commissioning executives refuse to dream, insisting instead on the dull materialism of returning series, “IP” and celebrity vehicles. It’s like the Great Nothing from Neverending Story, chewing its way remorselessly through imagination and a stable industry.

All the signs are that this destruction has not yet culminated. Over the past few years, the royalties that my companies receive from the streamers have declined by about two thirds, not because fewer people are watching, but simply because the streamers have decided to pay less in a one-sided, take-it-or-leave-it deal. Acquisition fees have similarly declined, commissions have dried up completely, advertising revenues are vastly diminished, linear tv is on its way out and with it the shared cultural experience is lowered into its final resting place. Real, proper news is under threat.

All of this hits the small independents particularly acutely, many have already gone. History (and Marx’s always accurate predictions) shows us that when industries come under this level of pressure, they enter a period of consolidation: most companies fail or are devoured by the bigger fish, who then form a cartel and dictate their terms. This is in turn leads to a crisis in plurality and creativity. Smaller creatives are presented with a miserable choice: either you work for the cartel or your work becomes a hobby.

We have an imminent, depressing example of this phenomenon: beginning this month Apple will take a 30% bite out of all the earnings that creators make through the Patreon app on iOS. Apple deliberately makes it incredibly hard for iPhone users to access and pay for services other than through its App Store, and will now use that leverage to divert into its own pocket a massive amount of what is a small sum of money pledged by individual members of the public in support of an independent creative whose work they enjoy. Why? To paraphrase Succession, so that Apple can have another billion dollars to throw on top of its pile of billions of dollars, and fuck it if the small creative’s income dries up.

We’ve already seen the sequence of collapse-consolidation-cartel on a grand scale in recent history, it happened to the music business back in the late nineties and early noughties. The music industry is now basically a cartel, it’s almost impossible for small and independent musicians to make a living by recording and selling music to music fans. Surviving now means sync licensing, writing on commission, live performance and a range of other business activities that alienate the artist from their art. Meanwhile the cartel acts to gate-keep the industry and rig it in its favour.

Yet there are reasons not to topple into fatalism, artists will always want to produce art, and audiences will always want to appreciate it. The challenge for independents is to find a means of reuniting these two constituencies within a commercially viable system of production and distribution.

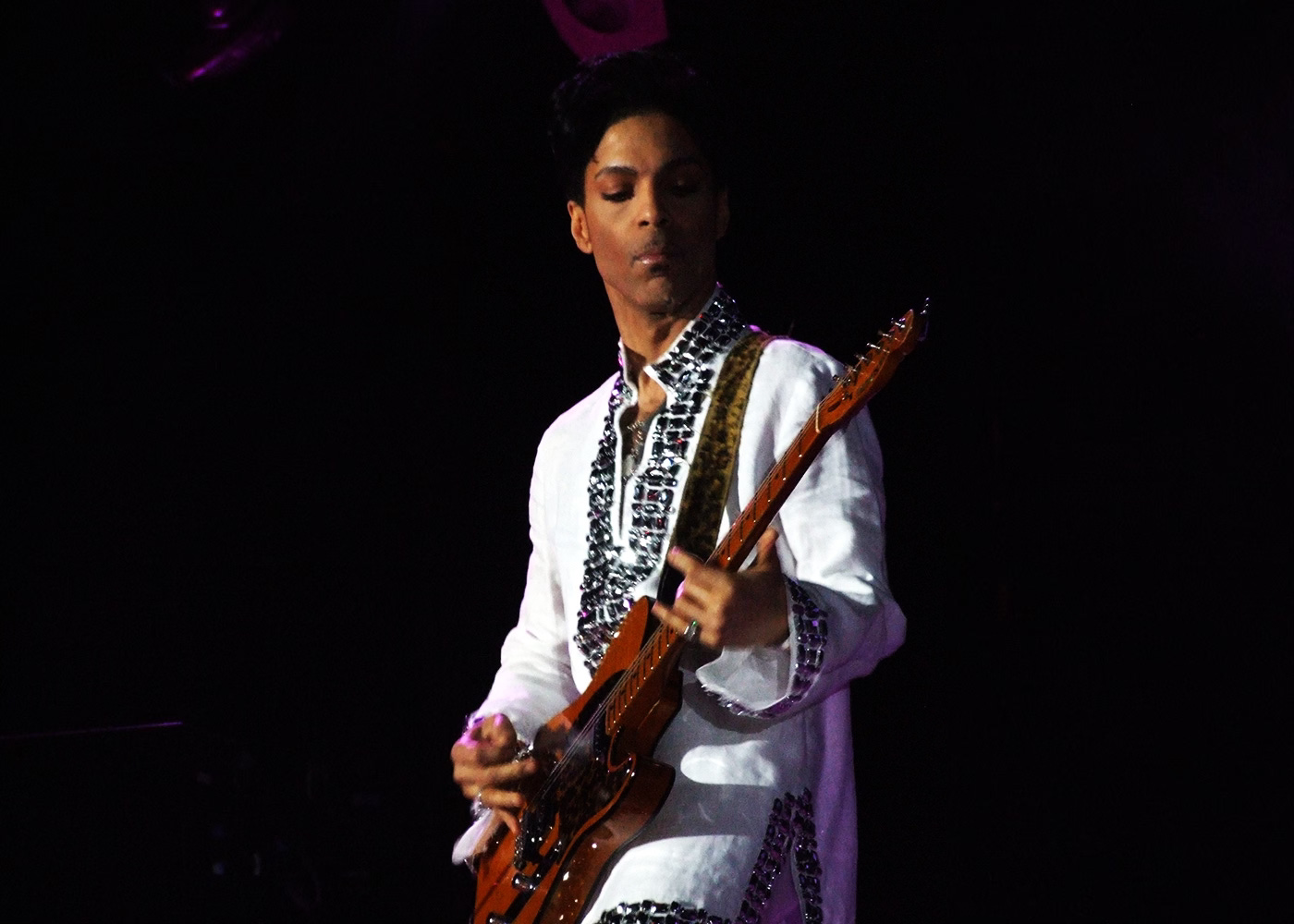

Interestingly, when the gears of the collapse and consolidation process first began to turn in the music business, a lone resistance fighter emerged: Prince. At the time he was derided as a nut, which he was not (at least not wholly), or a megalomaniac, which was more accurate, but he was able to see over the horizon to the coming, networked future and imagine a world in which the individual creator could build a more intimate connection with their audience, free from the parasitical manipulations of the cartel.

A few years back I made a film on this subject, I contacted Prince’s band, the New Power Generation, his business manager, Alan Leeds, as well as music industry executives. I’ll share those conversations in this article, they provide some lessons that I think are directly relevant to the current environment in which creatives are trying to produce and communicate art. It’s an interesting story.

SLAVE

In the early weeks of 1995, Prince started to appear in public with the word “slave” scrawled across his cheek, in angular, lacerating characters. It was a public declaration of war against the music business, a repudiation of the mediating power that record companies held over their artists and the culmination of a years-long ambition to break free of it.

Alan Leeds, Prince’s business manager:

Prince was both prophetic and way ahead of his time when it came to understanding the impact that the digital age would have on the music industry. You must understand that this was a guy who was already looking for alternative means to market and promote music to the public because he was so dissatisfied with the old business model. We had a meeting and this would have been 1990, 1991, where he called me in, and it was after he had delivered a record to Warners and was frustrated because they weren't in a hurry to put out another record again. The subject matter had once again become the fact that he was too prolific and giving Warners product too quickly.

And in his frustration, he was expressing to me, “you know, we've got to find another way to get music to the public. In fact, what if we went to late-night television and did like these oldies packages that people sell and we actually marketed a record on our own label to the public and we just sold it by mail order. We just do television adverts late at night and people write to a Post Office Box, or whatever, and we sell it through the mail”.

And I said, “yeah, that's great, except for one problem: you're in contract to Warner Brothers, you can't legally do that”.

“Well, then it'll be your label. You do it and we'll, we'll put a different name on it instead of Prince, we’ll put something else”.

And I said, “yeah, but they're not going to sit and let you do that. If you run a business, you can't allow that to happen. So put your Warner's hat on for a minute. Pretend you're [Warner’s CEO] Mo Ostin. What would you do? You're going to get a cease and desist and you're going to legally prevent us from doing that”.

“Well, I don't care. We got to do it”.

And I said, “furthermore, I'm president of a label that's a joint venture. I can't let you have me in jail. I can't be part of that and put it on my label”.

“Well, then put it in your wife's name. We'll call it Gwen Records”.

He was serious. I knew then that he was going to figure out some way to beat the system, even if it wasn't legally acceptable. He was going to push the envelope.

Michael Bland, drums, New Power Generation:

I think, like most artists, they don't really investigate until it's happening to them, and I think that's pretty much what Prince found himself doing, is examining more closely like, “well, how does this work?” Prince is a student and he likes to read and share ideas. So the more he got into the literature about the music business, the more upset he got. You know, and how it's designed. I mean it's systemic. That's what it does: you exploit an artist and they get paid a mere pittance compared to what you make.

The catalyst for Prince’s contretemps with Warner Brothers, was a landmark, $100m deal that he’d signed at the beginning of the ‘90s – “the biggest deal in the history of music” (although this claim was somewhat defied by the small print). As soon as the deal came into effect, the parties reached an impasse on how it would operate: Prince, an artist, wanted to produce and release music at the direction of his muse; Warners, a large corporate, wanted to maximise returns and so it refused to release Prince’s work at the pace that he wanted.

Alan Leeds:

The problem they were having with Prince was that he was producing too many records too quickly. Faster than their promotion and marketing machine could really digest, faster than the marketplace and the media could digest. We were in an era where most artists would release records anywhere from between 2 and 3 years apart, and he arguably could have had two records a year if he had wanted to. And he did want to, because he was of the mind that a record was like a newspaper. When it was finished, it was of that time: “I finished this song last night in the studio. I want people to hear it today. It's relevant to today. I produced it today. It's about how I feel today. People should hear it today”. And of course, the legitimate argument was that radio wasn't prepared to accept that much product from any single artist either. And as a result, it made it difficult for the label to promote it. So there really was a legitimate argument to space things out. It just didn't fit him as an artist.

Sonny T, bass, New Power Generation:

For me, that's their fault. That's not our fault. I mean, you know, if their machine can't keep up with us, what are we supposed to do? What's he supposed to do? You know, he got to get his music out. I mean, within reason. If the material is good, it should be marketed, it should be put out. There should be videos for it. [The artist] should be able to go on tour and they should be able to have support and, you know, do the things that they're supposed to do and have a successful record. Record company gets paid. They get paid.

In frustration, Prince attempted to find a way to circumvent the letter, not the spirit, of his contract. He floated the concept of releasing work under a different name to Warner Brothers, including a new album, Goldnigga, that could be issued as a New Power Generation project on his own label, arguing that it wouldn’t interfere with a more staged release of official “Prince” records through Warner Brothers. Warners was unmoved.

Michael Bland:

They didn't see the vision. You know, I think the idea behind the Goldnigga record was to put out an organic rap-slash-soul record, you know, with real instruments… we had worked on these tracks and friends had been driving around listening to it, it’s just like, “I really like this, you know, let's put it out”… Warner Brothers revealed that, “no, you can't do that. Anything you release, you know, has got to go through us”.

Feeling trapped, Prince tried to litigate the dispute in public, with a direct appeal to his fans. He refused to undertake promotional work on behalf of Warner Brothers and attempted to sabotage their marketing operation by changing his name from “Prince” to an unpronounceable symbol; anything to frustrate the label’s business, to match the frustration that they had imposed on his art.

Michael Bland:

The situation with Warner Brothers, with his audience as we were on tour… I think Prince was just trying to let them into his world to a certain degree, to let them know what he was going through. It was a monologue mostly. You know, he'd say something about Warner Brothers, and there's a lot of booing in the audience. And one night, I remember, they started chanting like, “Yeah, F- Warner Brothers” and Prince turned around on the mic and he was kind of cracking up and looking at us like, “you hear this??”

Exhausted by the adverse publicity and unmanageable relationship with their artist, Warner Brothers eventually acceded to one of Prince’s unabating requests that he be permitted to release a new single, The Most Beautiful Girl In The World, independently, on his own label.

Joe Levy, Billboard:

What Warners was betting was, “You want to release your music yourself? You think you know better than we do?...You want to do this yourself? Go right ahead. It's going to cost you a lot of money. You'll see. You need us. You don't really understand, radio promotion costs a lot of money. You'll see. You need us. As it turns out, he has a hit.

Michael Bland:

The litmus test was The Most Beautiful Girl In The World. Put the one single out, get the money behind it, you know, we did the whole world on that song.

Alan Leeds:

Warner Brothers letting him do it in a way slightly backfired on them because it kind of gave Prince all the ammunition he needed to be able to say, “I can do this on my own now”.

Michael Bland:

I'm privy to a conversation that he had with Mo Ostin around the time of the Gold Experience [album]. [Prince] mentioned the Gold Experience as a record he wanted to put out. We hadn’t begun working on this record yet. I think we had been talking about it. He got a phone call from Mo Ostin, they talked about other business and then Mo Ostin was like, “okay, well, as soon as you get that Gold Experience record finished, you know, send it right on, you know, and we’ll do what we do. Prince said “I haven't even started on it yet. I'm just conceiving it in my brain” and Mo is like, “well you know, either way it's ours, so…” and I think Prince, at that point, made an epiphany that “this company thinks that they own the ideas that are in my head. I haven't even begun to put anything on tape, and they're already talking about what they're going to do with it”. So I think that was really the point at which Prince realised, “I can't do this anymore” and he walks into rehearsal he’s got “slave” written on his face, and, you know, he's like, “this is it”.

Joe Levy:

His complaint is that Warners isn't giving him ownership of his intellectual property. That's the way we would phrase it today. It becomes an intellectual property battle: “I made this music. Why don't I own it? Why don't I own my masters? Why don't I own my publishing?” …at that time, these were things that, you know, musicians didn't talk about that much. Now it’s not that unusual to find either an indie musician talking about, “Well, I want to stay in an indie label because I want to own my work” or to find someone, a veteran artist, saying, “I'm suing my record company to get back my rights because under copyright law…” At that time, we weren't really used to artists making these complaints. It seemed like bellyaching. I mean, it seemed like someone who was famous and rich complaining that he wasn't rich enough… Turns out we would all end up caring about this stuff, but we didn't know at the time.

Prince (speaking in 1995):

In 1999 we’ll be free, and we can sell the music directly to the consumer. And we can give it away if we want.

The New Frontier

The dispute between Prince and Warners eventually concluded with both parties agreeing to go their separate ways. Warners, of course, still retained rights over Prince’s back catalogue, including all the spectacular hits and radio staples from the ‘80s. For his part, Prince wandered into uncharted territory, tarnished by the row, his reputation injured by the sub-standard material that he had been feeding to Warners in satisfaction of his contractual obligations. He became an international curiosity: a high-profile artist without a record contract nor, apparently, any intention to get one.

Alan Leeds:

In retrospect, Prince's problem really wasn't with Warners as much as it was the industry itself. I mean, Prince was ahead of his time. He was absolutely right. Many of the things that he griped about, I thought he was dead on. Record companies had their heads in the sand. They were all on automatic pilot. The business model was stale. We would have meetings where he would frustratingly want to figure out alternative ways to release and promote records because he was so dissatisfied with how labels conducted business. Now, he was signed to Warner, so of course this frustration is directed to Warners because that's who he was in business with. But it wouldn't have been any different had he been signed to Columbia or RCA or any place else, because it was the business model itself, the industry and how it functioned, that frustrated him.

In 1996 Prince’s first self-released album, Emancipation, hit the record stores. Although sales figures were far smaller than the numbers generated by Warner’s promotional behemoth, more of the profits remained with Prince, who made much more than he would have done at the label. A tour, Jam of the Year, followed, in which he sought to shake up the live music business by cutting out the major concert promoters and booking his own shows. His earnings from the tour alone were estimated to have reached $30m.

In 1997 he made an unprecedented, early foray into e-commerce, promising to release a three-disc boxset if he received enough advance orders through his website, loveforoneanother.com and his telephone hotline, 1-800-New-Funk. Taken together, all these initiatives represented a full spectrum assault on the established practices of the music business as Prince sought to become a fully self-contained artistic and commercial entity.

Michael Bland:

I remember him telling us, “one day music is going to be sold, you know, back and forth by computers”, and we're like, “Get out of here, man! What are you talking about!?” But lo and behold.

Alan Leeds:

Prince doesn't get enough credit for what he was doing in the late 90s. When Radiohead released their In Rainbows box set through their website in 2007, that's ten years later, but people acted like it was the first time anyone had ever done this sort of thing. But what Prince is doing in ’97, is taking pre-orders for the Crystal Ball boxset. And he became the first artist to sell an entire album online, directed to his fans. The whole marketing thing went straight to the people who he wanted to sell it to. There was no middleman. There was no need for a record label. Prince just took it all under his own umbrella organisation. And I think that is incredibly forward thinking.

At the turn of the millennium Prince was vindicated when the music industry suddenly, spectacularly imploded. Over the course of the 1990s, the industry had become a risk-averse, money-making machine, monopolised by just a few major labels who used their muscle to arrange the market in their favour and dictated their terms to artists and consumers alike. The quiet migration of Prince and others to the internet proved to be the precursor to a general exodus. When the peer-to-peer file sharing website Napster launched in 1999, consumers rushed to download and distribute music free of charge, and having neglected to develop a viable commercial presence in cyberspace, the industry was overwhelmed.

Alan Leeds:

They had their heads in the sand, and the evidence is very plain and simple: Napster came from outside the industry. The record industry was so myopic about technology. All a record company knew in the ‘80s was if you had a new product, you went to the radio station, programmers that you knew, you made a video and you took it to MTV and anybody else who would play a video, and you had a PR person go to the print media, into any magazine and anybody else who might write something about your artist; you hired friends of friends, the people that worked for labels used to be programmers at radio stations. I mean, it was this inbred world that had fed on itself for so many years, and basically it had worked so successfully and so many careers had been made by it, and people were loyal to it, and they took vacations together and they partied together and they married each other. And it was this whole atmosphere of we have this winning business model, so let's not fix it if it isn't broken. Well, the problem was it was broken.

Jem Aswad, former Warner Brothers executive:

Nobody saw the digital revolution coming to the degree that Prince did.

Alan Leeds:

The industry was gone. It was over, just literally overnight. And I remember there used to be little signs of worry. Something's going to change here, but we don't know what it is. And we're not really taking the time to figure out what it is. We're just going to wait and react because what we have is too good, it's too easy and it's working too well, so we'll just kind of wallow in it. And when the shit hits the fan we’ll react to it. Well, too late.

This is where the music business ran into its black hour, the insolvencies, the unviabilities, the redundancies and collapses and inabilities. And then the consolidation, as the implacable mouth of capital yawned and swallowed all before it.

But Prince was just fine. Untouched by all the strife he continued to innovate means of reaching his audience and making sense of the restless economics. In 2001 he pioneered the type of subscription service that would become ubiquitous almost two decades later with his online NPG Music Club, where subscribers would receive experimental, digital-only albums. His Musicology download store launched before iTunes. In 2004 he gave away copies of his new album free with concert tickets, to his enduring satisfaction it provoked howls of protest from the major record labels, but also prefaced an industry-wide shift from CDs to gigs as the primary source of artist income.

In 2007 he released a new album, Planet Earth, as a free cover mount on the Mail on Sunday newspaper in Britain. He received more from the paper than he would have done in an advance from a record label, and again used the album to promote a new live show in London, another ground-breaking concept: a 21-night residency at a single venue, the o2, which meant that Prince could avoid all the transport and staging costs of moving around different venues.

Prince was able to produce, release and promote precisely the art that he wanted, on his own terms and according to his own schedule, without recourse to the music industry and its cartel. He won.

Of course, he had a head start. The fact remains that Prince was the beneficiary of the major-label juggernaut and its massive powers of promotion and exposure during its all-conquering glory era. He did not have to face surviving in a depleting industry as an obscure creative, rich in ambition but starved of money. Nevertheless, I think the basic elements of his analysis and approach are pertinent no matter what your professional circumstances, nor the level of your obscurity.

I remember, years ago, probably in the pre-social media days, seeing a review of one of our films online. The journalist remarked that he had tried to obtain an interview with the filmmakers, but that we were “about as outgoing as Howard Hughes on a bad day”. At that point we were relentlessly busy, and had neither time nor appetite for engaging in promotion, which we felt to be unnecessary. But that journalist was out there, trying to find us.

Over the years our films have been watched and enjoyed by millions of people. Those people remain out there but, as of the time of writing, I don’t know how or where to find them. Many of the audiences that appreciated our work have been abandoned by television, discarded in the consolidation, not because they no longer exist, but because corporate executives have concluded that they’re not as valuable as the audience for, say, true crime, or celebrity-driven, reality TV.

The challenge during any large upheaval will always be to reunite the creatives with their audience, and I remain convinced, during this latest, that there are ways to do so without capitulation to the cartel, or to the Apples of this world. I offer the story of how Prince did it.